On Feb. 24, John Hamm, the director of Alabama's Department of Corrections, informed Gov. Kay Ivey that he had completed the investigation of the state's execution process that she requested last November. He wrote her a brief letter describing what that investigation entailed and what changes he was implementing as a result.

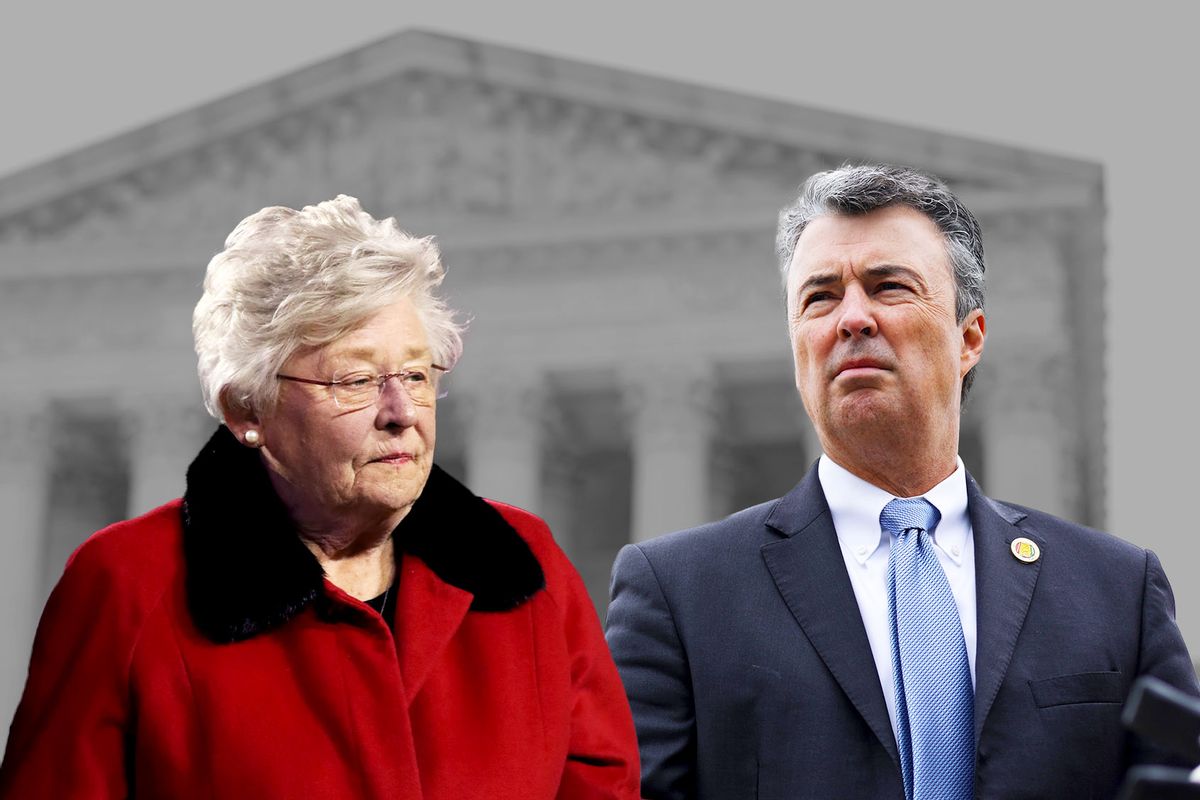

Despite the report's brevity, Ivey seems neither to have asked any questions nor requested more information. The next day she sent a letter to Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall asking him to seek execution dates for people on the state's death row as soon as possible.

Marshall quickly complied. The day he received Ivey's request, he filed a motion with the state Supreme Court asking it to set an execution date for James Barber, who has been on death row since 2004. Barber was sentenced to death for killing a 75-year-old woman.

Marshall also told the governor that his office would be "seeking death warrants for other murderers in short order."

These grim exchanges may put Alabama back in the execution business, but they leave many questions unanswered. Without those answers, we cannot possibly know whether the changes Hamm is implementing will prevent Alabama's executions from again becoming gruesome spectacles of suffering for those the state puts to death.

In fact, the governor and the attorney general went to great lengths to make clear that they care more about restarting executions and satisfying murder victims' families than about what people condemned to death experience in the state's execution chamber.

As Ivey noted in her letter to Marshall, "Far too many Alabama families have waited for far too long — often for decades, to obtain justice for the loss of a loved one and to obtain closure for themselves."

"Now it is time," the governor said, "to resume our duty of carrying out lawful death sentences."

The only thing Ivey had to say about the condemned was to criticize them for throwing sand into the machinery of death. As she put it, they will "continue doing everything in their power to evade justice."

Marshall echoed the governor's tough-on-crime soundbite language, adding that "those on death row — as well as their victims — can be certain that I and my office will always do our part to ensure that they receive just punishment."

But Hamm's Feb. 24 letter offers little assurance that Alabama's death penalty can and will be carried out justly. It neither discusses what went wrong in last year's string of botched executions nor identifies what caused them.

It says almost nothing about how the Department of Corrections carried out its in-house investigation, or what changes it will make in its execution protocol. And as if to deepen the mystery, the Department of Corrections says that no other statement or additional details would be forthcoming.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

About the investigation process itself, Hamm wrote, "The Department conducted an in-depth review of our execution process that included evaluating: the Department's legal strategy in capital litigation matters (and) training procedures for Department staff and medical personnel involved in executions…."

Who, if anyone, was interviewed as part of the review? What were they asked? Were they under oath? What did they say about the problems that have plagued Alabama's death penalty system?

Hamm's letter doesn't give a clue.

It does note that "during our review, Department personnel communicated with corrections personnel responsible for conducting executions in several other states. Our review also included thorough reviews of execution procedures from multiple states to ensure that our process aligns with the best practices in other jurisdictions."

But again, crucial details are missing and question are left unanswered.

How many people were contacted, and in which states? What changes did they recommend in Alabama's execution procedures? What comprises the "best practices in other jurisdictions"? Which of those practices did the Alabama Department of Corrections consider but not adopt? And if such a decision was made, why?

Turning to the changes Alabama plans to make for future executions, we again learn little.

Hamm's letter contains just two short paragraphs describing those changes and offers no explanation of why they are being made. Neither its brevity nor omissions are "best practices" when it comes to investigations and the final reports they are meant to yield.

The Department of Corrections, Hamm writes, has "decided to add to its pool of available medical personnel for executions. The vetting process for these new outside medical professionals will begin immediately."

He does not say how many medical people will be added, what their qualifications will be, what the vetting process will entail or, most importantly, what they will be asked to do.

Hamm adds that his department "has ordered and obtained new equipment that is now available for use in future executions." This suggests that equipment failures might have caused problems in the past, but his letter says nothing about what those problems were or what "new equipment is now available."

Both the governor and attorney general made clear that they care much more about restarting executions than about what people condemned to death may experience in the execution chamber.

Hamm reported that the people in his department responsible for carrying out executions "have conducted multiple rehearsals of our execution process in recent months to ensure that our staff members are well-trained and prepared to perform their duties during the execution process. We will continue to update our rehearsal and training procedure to ensure that Department personnel are in the best possible position to carry out their responsibilities during the execution process."

"Multiple rehearsals" — what does that mean, exactly? Two or three? Ten or 20? Who was in charge of the training, and what did they observe? How often will procedures be updated, and who will be tasked to ensure that this is done?

The one change about which Hamm's letter offers any detail is particularly worrisome.

"The Supreme Court of Alabama," he reminds Ivey, "changed its rule for scheduling executions…. [U]nder the new rule, the Court will issue an order permitting you to set a 'time frame' for the execution to occur. This change will make it harder for inmates to 'run out the clock' with last-minute appeals and requests for stays of execution."

The court's decision ensures that if things go wrong in the execution chamber, the state can do whatever it wants with inmates for as long as it wants, no matter how much suffering they endure.

In the end, Hamm's letter offers no evidence that his department's investigation was thorough or that the changes it mentions will be adequate. It reads as if Hamm was saying, as Richard Dieter, interim executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, puts it, "'Trust us, we did everything.'"

Given Alabama's dismal execution track record and its disregard for the rights of the people it executes, there is no reason for death row inmates, citizens or judges charged to protect those rights to trust this report. All of those people need to know a great deal more before Alabama is allowed to try carrying out another execution.

Read more

from Austin Sarat on capital punishment

Shares