Joe Biden is not the first president to have a secret cancer surgery.

At the time of this writing, the only confirmed facts are that a small lesion was discovered on President Biden's skin — and that it was later found to have been cancerous. Specifically, it was a basal cell carcinoma (BCC), a common type of skin cancer with an excellent prognosis for recovery. (BCC rarely returns or spreads to other parts of the body.)

The incident has some odd parallels with an incident that happened 130 years ago, when America had a president who discovered a deadly tumor on the roof of his mouth. Whereas Biden only kept his surgery secret for a few weeks, this president went to his grave never admitting that he had had an operation during his presidency. Indeed, it took almost a quarter-century for the truth to come out.

[The sore patch] was "an ulcer as large as a quarter of a dollar, extending from the molar teeth to within one-third of an inch of the middle line and encroaching slightly on the soft palate."

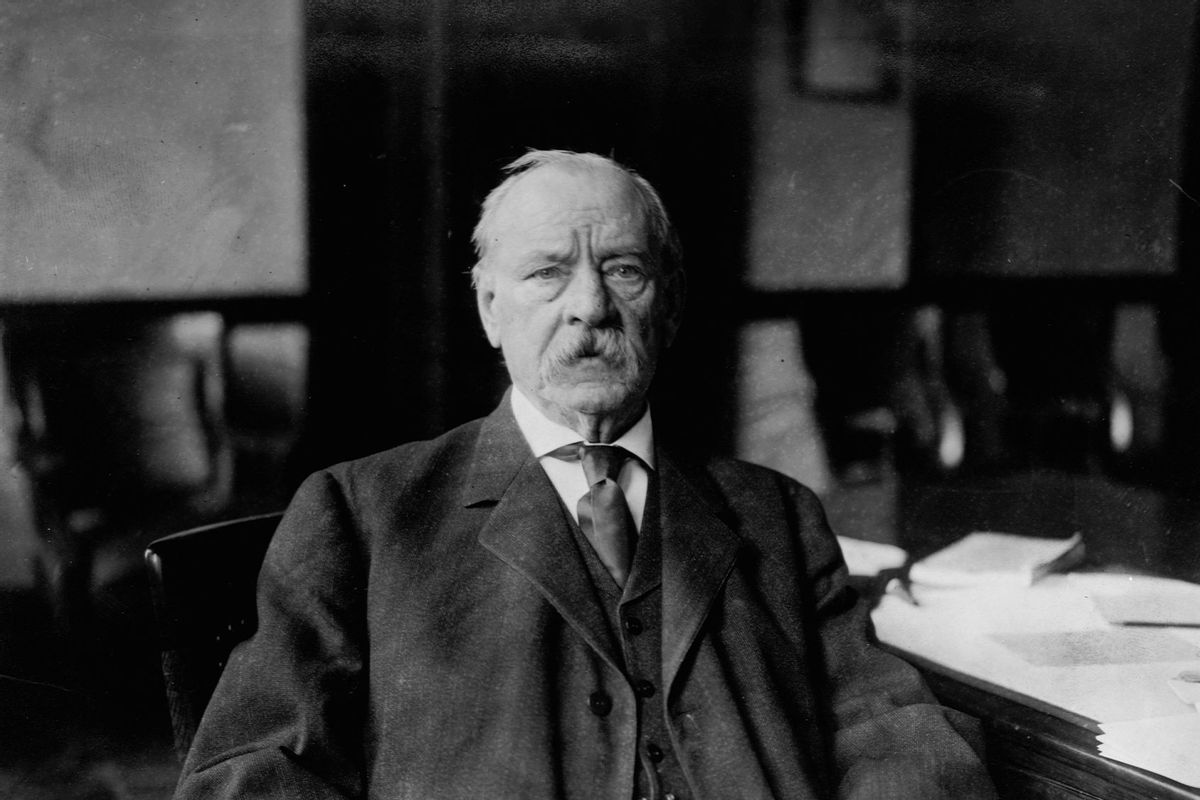

The president in question was Grover Cleveland, best known as the only American president to serve two non-consecutive terms. Our story begins in 1893, at the start of Cleveland's second term, when America was grappling with the worst economic depression in its history (up to that time). As a lifelong conservative, Cleveland believed the government should not provide any relief to the impoverished citizens; instead he wanted to maintain America's gold reserves and otherwise cultivate a healthy business environment. Philosophically, Cleveland was as opposed to labor activists like Eugene Debs as he was to bimetallic populists like William Jennings Bryan. Whether or not one shares Cleveland's views, he was unquestionably sincere in his conviction that America needed a steady and nonpartisan hand at its helm during its harrowing economic ordeal. Consequently, Cleveland emphatically did not want power to fall into the hands of Vice President Adlai E. Stevenson, a career politician who wanted to solve the depression through bimetallism (Bryan's proposal to expand monetary policy by allowing the unlimited coinage of silver).

It was during the midst of this high-stakes, high-pressure moment in history that Cleveland suddenly discovered a sore rough patch in his mouth.

Thanks to a 1917 account written by one of the surgeons present, Dr. William W. Keen, we know that it was "an ulcer as large as a quarter of a dollar, extending from the molar teeth to within one-third of an inch of the middle line and encroaching slightly on the soft palate, and some diseased bone." A sample was removed and a pathologist was selected who would have no idea of the patient's identity; the pathologist diagnosed it as "strongly indicative of malignancy." Cleveland quickly decided that the tumor had to be removed as soon as possible; Congress was scheduled to meet in August to make critical decisions on economic policy, and Cleveland believed his active presence was vital to the republic's future. Within weeks, Cleveland had made all the arrangements, and on July 1, 1893, surgeons operated on him aboard a yacht called Oneida, which lolled gently along the Long Island coast.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

"The doctors who operated on Cleveland were using equipment and techniques that would appear almost medieval to us today."

The doctors' biggest concern was knocking Cleveland out. "The patient was 56 years of age, very corpulent, with a short, thick neck, just the build and age for a possible apoplexy," observed Keen, who had experienced that exact complication with one of his own patients. As such "our anxiety related not so much to the operation itself as to the anesthetic and its possible dangers." In addition, Cleveland was experiencing tremendous stress due to his job, which further worsened his health.

Fortunately for Cleveland, his doctors were more competent than those who unsuccessfully attempted to remove a bullet from President James Garfield's back only a dozen years earlier. These doctors successfully anesthetized their patient with nitrous oxide and ether, then surgically extracted the following:

The entire left upper jaw was removed from the first bicuspid tooth to just beyond the last molar, and nearly up to the middle line... A small portion of the soft palate was removed. This extensive operation was decided upon because we found that the antrum — the large hollow cavity in the upper jaw — was partly filled by a gelatinous mass, evidently a sarcoma.

After the surgery "a hypodermic of one-sixth of a grain of morphine was given — the only narcotic administered at any time." Before long Cleveland was back to work as president. The press suspected something was amiss — American politics, then as now, was full of leakers — but no one came close to unearthing the surgery. It took Keen's confession for the truth to come out... and what a truth it was.

"An oral surgeon I spoke with expressed amazement that the surgery was performed so quickly (in about 90 minutes) and successfully (the patient survived another fifteen years)," writes Matthew Algeo, journalist and author of "The President Is a Sick Man," an account of the surgery. "The treatment Cleveland received is the same treatment recommended today: surgical removal of the tumor. But the doctors who operated on Cleveland were using equipment and techniques that would appear almost medieval to us today. There was no operating table; he sat in a chair with his head resting on pillows. The only artificial light available was a small light bulb attached to a portable battery."

It is also difficult to not be impressed with Cleveland's character during this anecdote. Democrats today would likely not agree with Cleveland on most issues; he was president at a time when Democrats tended to be conservative and Republicans tended to be liberal. Nevertheless, Cleveland was known by all to be an extremely stubborn man, and the same mulishness that could make him an obsessive ideologue also gave him great strength of spirit as he struggled with what was undoubtedly unbearable pain.

"After several weeks he was fitted with a prosthesis, a piece of vulcanized rubber that attached to his (remaining) upper teeth. This restored his normal speaking voice, which was crucial to maintaining the cover-up."

"He experienced considerable post-operative discomfort," Algeo told Salon. "The surgery left a large cavity in his upper palate that was packed with cotton gauze. This made eating and drinking difficult and his speech unintelligible. After several weeks he was fitted with a prosthesis, a piece of vulcanized rubber that attached to his (remaining) upper teeth. This restored his normal speaking voice, which was crucial to maintaining the cover-up. But he would remain in some discomfort more or less for the rest of his life."

Given that Cleveland was only human, the upstate New Yorker already notorious for a sullen and phlegmatic disposition became even more prone to unpleasantness.

"Friends and associates said his temper became much shorter after the operation, given to outbursts and rash decisions," Algeo wrote to Salon.

Despite these flaws, Cleveland's handling of the surgery is one that patients everywhere should internalize. If Dr. Keen is to be believed, Cleveland was a dream patient — at least, according to a distinctly conservative view of how an ideal patient ought to behave.

"For a man of his rugged temperament, self-conscious power, and concentrated will and purpose, he was the most docile and courageous patient I ever had the pleasure of attending," Keen wrote. "Once a decision was reached and announced to him, he observed the prescribed regimen steadfastly and with unquestioning obedience."

Shares