In Mike Judge's 1999 hit "Office Space," Ron Livingston's character, Peter, has had enough of his numbing office job at software company, Initech. He decides to try to get fired on purpose. That works out pretty well for him. So well, in fact, his company wants to promote him. His antics, from dressing down to ignoring his boss to cleaning fish at his desk, and total disinterest in work only prove he has upper management potential, sort of like a cubicle Patrick Bateman.

The present-day equivalent to Peter might be Hank of "Lucky Hank," AMC's adaption of Richard Russo's novel "Straight Man." How is Hank lucky? Well, he hasn't been fired yet, despite doing a lot of things to merit it. He's not the only one in the show who hates their job and lets it be known. From a bar employee to a college president, "Lucky Hank" may be the best example yet of the phenomenon known as quiet quitting.

In July of 2022, a TikTok from engineer Zaid Khan went viral. Khan's soothing voice narrates scenes of waiting for the subway, viewing leafy trees in the park, blowing bubbles. He says, "I recently learned about this term called quiet quitting, where you're not outright quitting your job but you're quitting the idea of going above and beyond. You're still performing your duties, but you're no longer subscribing to the hustle-culture mentality that work has to be your life. The reality is it's not."

Within days The Guardian had published an explainer, the first of many pieces unpacking this term, why it seemed to resonate and what to do about it. The Guardian wrote, "The meaninglessness of modern work – and the pandemic – has led many to question." Quiet quitting was a catchy term, much less cumbersome than feeling very tired and burnt out because life is really hard right now and expensive and dangerous with COVID and maybe we should focus on the escalating climate crisis and spending time with our loved ones, etc. Now we had a catchall for the feelings of exhaustion and disillusionment — and corporations had a scapegoat.

Quiet quitting is "Worse Than the Real Thing," read the headline on an alarmist piece from the Harvard Business Review. A CNBC contributor, interviewed for an article on the trend in The Wall Street Journal, said it was "worse than COVID" and called one who would engage in such detachment "a loser."

Mireille Enos as Lily and Bob Odenkirk as Hank in "Lucky Hank" (Sergei Bachlakov/AMC)The dusty halls and high towers of academia are not known for jumping on trends so it took time for the term to reach professors. But reach them it has. Last month, Nature published an article examining the trend of academics quiet quitting: trying to restrict work hours and set more boundaries when it comes to things like meeting students, serving on committees and peer reviewing articles.

Mireille Enos as Lily and Bob Odenkirk as Hank in "Lucky Hank" (Sergei Bachlakov/AMC)The dusty halls and high towers of academia are not known for jumping on trends so it took time for the term to reach professors. But reach them it has. Last month, Nature published an article examining the trend of academics quiet quitting: trying to restrict work hours and set more boundaries when it comes to things like meeting students, serving on committees and peer reviewing articles.

He's too young to retire, too old to care.

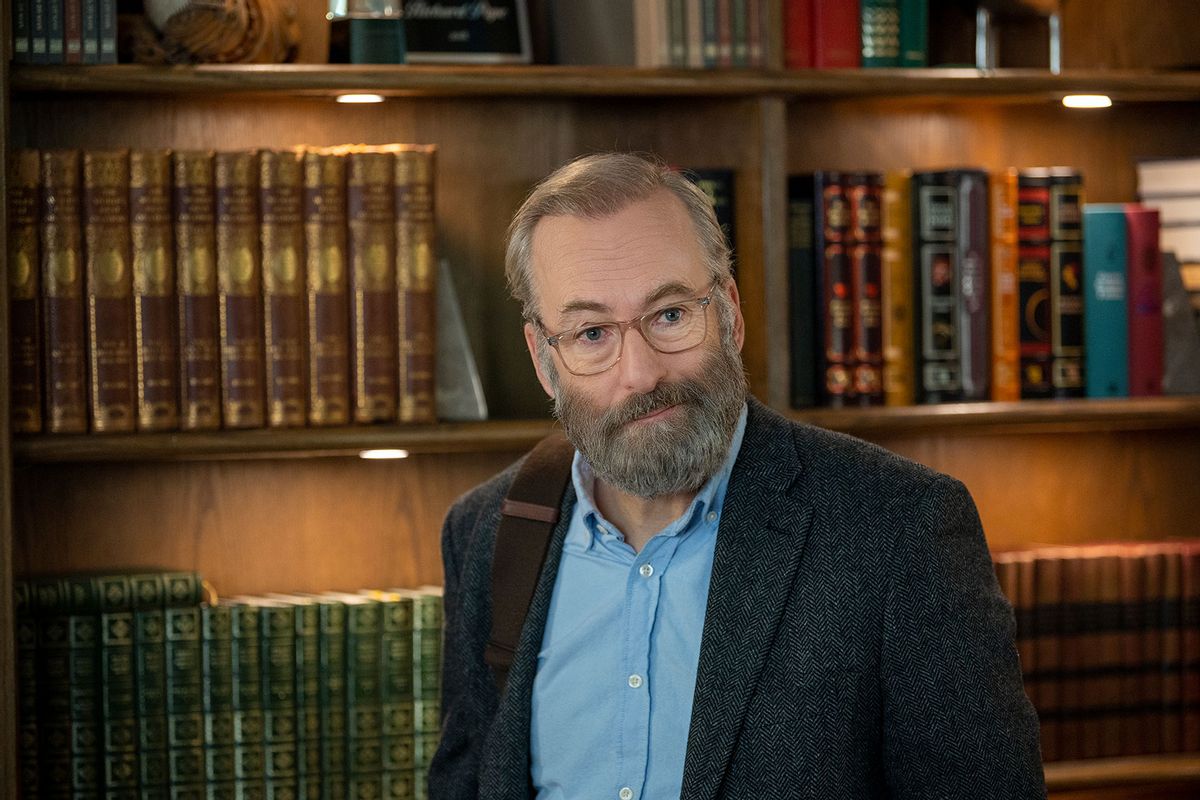

For Hank (Bob Odenkirk), the working years have taken a toll. In the pilot of "Lucky Hank," he tells an arrogant creative writing student exactly what he thinks of their work. He's bitter. He's tired. In later episodes, he gets drunk before needing to introduce an important writer at a big event (it's George Saunders, though not played by George Saunders). Hank boxes a goose, or realistically threatens to. All of these are public demonstrations of his disdain for work, at high-profile events. Like Peter, he's not hiding his distaste for the (academic gowned) hand that feeds him. He's too young to retire, too old to care.

Hank knows he's given a lot of his life to a not-great school — and his own creative work, fiction writing, maybe the labor he actually cares about, has suffered as a result. Hank's wife Lily (Mireille Enos) has also devoted her career and way too much time to a school that doesn't love her back, a high school whose students (and worse, administration) don't respect her.

Even the college president, the great Kyle MacLachlan as the awesomely named Dickie Pope seems to be phoning it in. He's got a cool detachment starting from his first appearance in Episode 4 "The Goose Boxer" when he calls Hank into his office. Hank is in trouble but neither man seem to care, the one being reprimanded or the one doing the reprimanding. President Pope is not going to ask for more money for the school, not going to say goodbye at any point; he simply strides out of the room, unconcerned. Nothing fazes him, including the fact that a huge donated building is named after Jeffrey Epstein (a different Jeffrey Epstein, OK?). Dickie Pope has evolved.

Kyle MacLachlan as Dickie Pope in "Lucky Hank" (Sergei Bachlakov/AMC)

Kyle MacLachlan as Dickie Pope in "Lucky Hank" (Sergei Bachlakov/AMC)

The only person I know who doesn't have a problem with taking work home, working after work hours, is a line cook who isn't buried in emails.

Hank tunes out during a colleague's tirade. The show gives us his inner monologue at times, including wondering about the architectural model on the president's desk, and if it's hard to break into the "tiny-tree business." Hank's son-in-law Russell (Daniel Doheny) isn't thrilled with any work, including the job Hank gets him at the local bar run by Meg (the likeable Sara Amini) but the primary quiet quitting we have here is from the burnout factory known as education.

There is a certain romance that some academics, perhaps especially lifers like Hank, seem to have for other professions. When I transitioned from academia — where I never landed a tenure track job — to journalism, I lost count of the number of professors (tenured professors!) who reached out to me asking how they too could make the move. They didn't seem to like my answer: interview for dozens of academic jobs you don't get and work for years below the poverty line hustling as a freelance reporter, publishing nonstop. Is this a misguided elevation of other work or just a misunderstanding of how most work works? The only person I know who doesn't have a problem with taking work home, working after work hours, is a line cook who isn't buried in emails. Though of course the food industry has its own struggles with burnout too.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

All of these people in the academic universe of "Lucky Hank" (with the exception of Meg, who works as an adjunct/bartender) have good jobs. We assume their salaries are decent, enough to buy nice houses and drive cars in various degrees of niceness, and they have health insurance, fancy dinners and gym memberships. Also, once they have tenure it's very, very hard to fire them.

Most of us don't have that kind of job security. If professors can't make it without quiet quitting, then maybe none of us can. Work is hard. Capitalism is hard. The world is pretty hard right now. Let's all go sit in a park, look at the trees and maybe blow some bubbles for a while.

Shares