The average person has 100,000 hairs sprouting from their scalp, and every one of them tells a story about who they're attached to. Hair follicles are connected to the bloodstream, which means they can absorb the metabolites of drugs like psychedelics, opioids, cannabis and more. The drugs and their metabolic byproducts then bind to the melanin in hair, locking in evidence of intoxication that stick around in hair even centuries after the person they're attached to has died.

Es Càrritx is often called a "cult cave" — so named because, approximately 3,600 years ago, it was host to various ritual activities.

Now, a new analysis of hair samples from an island cave off the coast of Spain confirmed that such drug use is nothing new for humanity. Evidently our distant ancestors were getting stoned on some interesting substances, as detailed in the journal Scientific Reports by a group of anthropologists from the University of Valladolid and the Autonomous University of Barcelona. Using forensic toxicology approaches, they analyzed samples of cadavers from the Es Càrritx cave, nestled in the Algendar ravine on Menorca island, providing some of the best evidence to date that ancient Europeans were getting extremely high relatively often.

Es Càrritx is often called a "cult cave" — so named because, approximately 3,600 years ago, it was host to various ritual activities. It later became a burial ground for about 200 people over several centuries. Some of the funerary rituals performed in this cave involved dying certain corpses' hair red; other people's locks were combed, cut and stuffed into tubes made of antler or wood with trippy, eye-like markings carved into the lids.

The hairs and their wooden canisters were analyzed with radiocarbon dating, indicating they were buried in the Late Bronze Age around 3000 years ago. But when the hairs were also screened for drugs, the researchers uncovered a trio of naturally-occurring substances called atropine, scopolamine and ephedrine.

"Considering the potential toxicity of the alkaloids found in the hair, their handling, use, and applications represented highly specialized knowledge," the authors report. "This knowledge was typically possessed by shamans, who were capable of controlling the side-effects of the plant drugs through an ecstasy that made diagnosis or divination possible."

Ephedrine is a stimulant that promotes alertness, squashes appetite and can treat colds. It's produced by many native plants across the world, including in China, the U.S. and Europe. The cold medication pseudoephedrine is a slightly tweaked version of ephedrine, while methamphetamine is a close analog. Its closeness to meth has made it an attractive natural precursor for producing large quantities of the drug in places like Afghanistan.

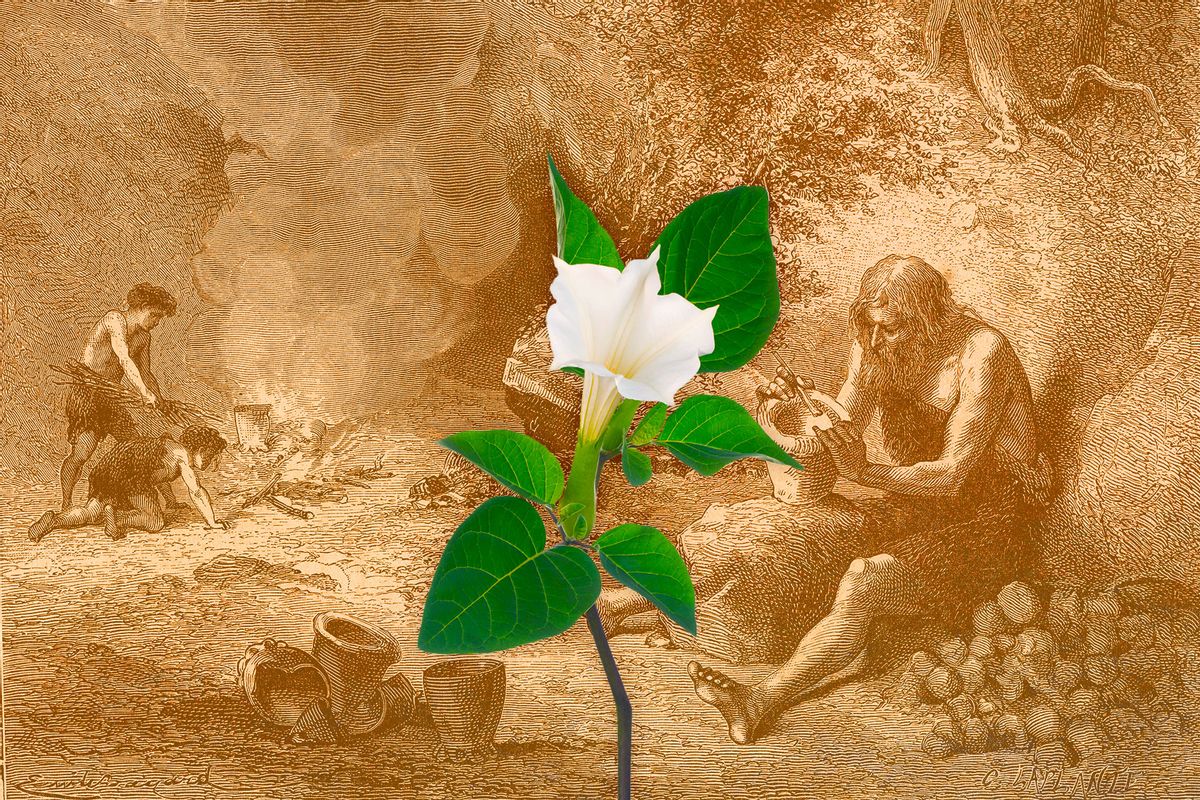

The plant that these Bronze Age people were most likely eating was thornapple, also known as jimsonweed.

On the other hand, atropine and scopolamine are two closely related hallucinogens that are profoundly different than the "classic" psychedelics like psilocybin or DMT. Instead, they're both deliriants — that is, they trigger delirium, which can often become overwhelming or unpleasant. This state of mind is colored by confusion, agitation, memory impairment and vivid, dream-like hallucinations.

Plants like henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) and belladonna (Atropa belladonna) produce atropine and scopolamine, but the plant that these Bronze Age people were most likely eating was thornapple (Datura stramonium), also known as jimsonweed. It has distinct, spiky seedpods and muted lavender flowers but many people who have eaten this plant, intentionally or not, have reported some potent, often nightmarish trips.

Some experience reports with thornapple include losing the ability to read for days, feeling clawed by a giant eagle and watching while everyone died and decayed around them as Superman crucified himself. Thornapple likes to grow near crop fields, sometimes contaminating vegetable produce, which has hospitalized many people and triggered massive recalls.

So what were these ancient people ingesting these plants for, anyway? They may have been seeking medicinal relief, or taken them as part of shamanic religious practices, or both. But one thing is for certain: it seems like they were doing these drugs often.

"The length of the hair strands and the analysis of segments all along the hair shafts point to consumption over a period of nearly a year," the authors wrote. "Hence, drug intake was sustained over time probably well before death."

That stands in contrast to the mummified heads and cadavers discovered on the Southern coast of Peru, whose hair was analyzed last year, revealing another diary of drug use from 500 to 2100 years ago. As previously reported in Salon, the hair of these individuals revealed they were taking hallucinogenic San Pedro cactus, some of the components of the psychedelic brew ayahuasca and likely even chewed coca leaves, which contain cocaine. But these people were likely fed psychedelics before being ritually sacrificed, rather than taking them regularly.

The Spanish island cave discovery is some of the oldest direct evidence of drug use in European history. This has been hinted at before through other archaeological discoveries, such as traces of opium poppies or ephedrine-containing yew trees, but the presence of these drugs alone hasn't been enough to prove that people actually consumed them.

The history of European drug culture is increasingly relevant as psychedelic experiences are often popularly perceived of as South American or African cultures' indigenous rituals that are being "colonized" and co-opted by Westerners. Finding ephedrine, atropine and scopolamine in hair samples is some of the most solid evidence to date that drug use has been a long part of human history all over the world, including in ancient European cultures.

Shares