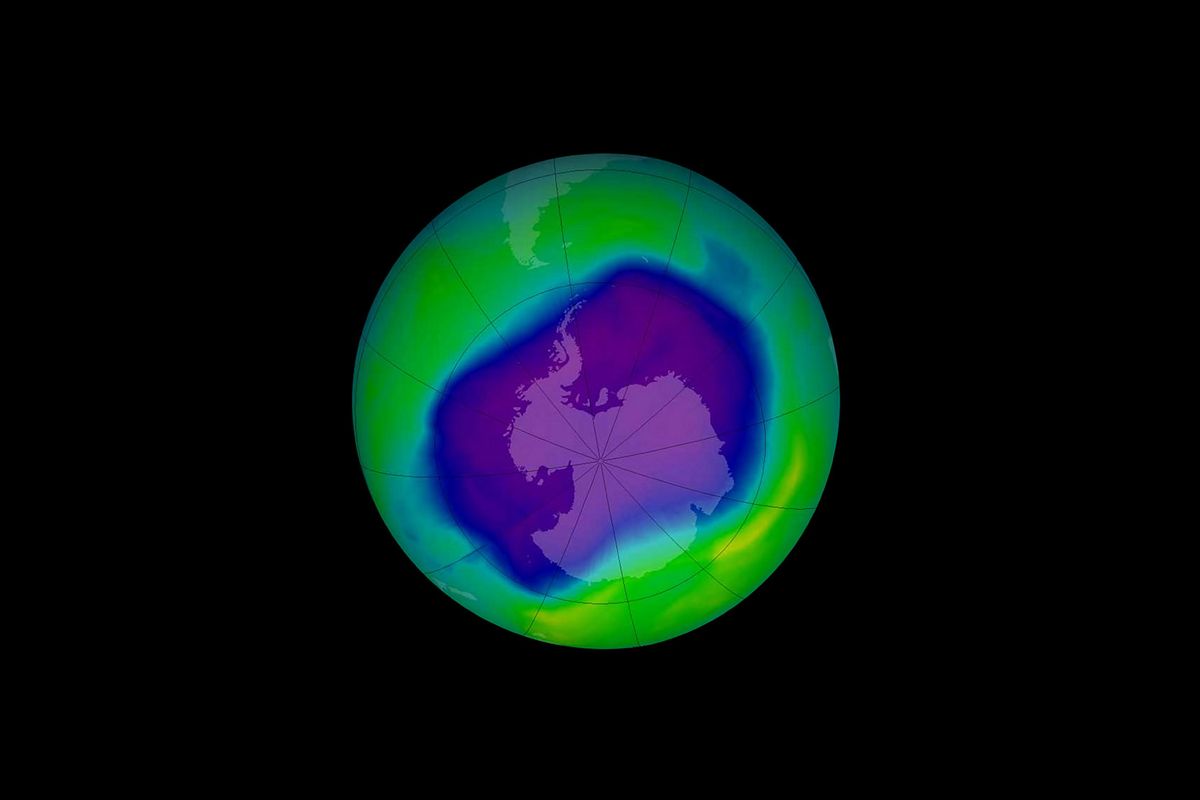

The hole in Earth's ozone layer — which made headlines in the 1970s and 1980s but which has been slowly healing since an international treaty banned the chemicals creating it — is growing bigger again. The culprit is an increase in the release of banned chlorofluorocarbon gases, which break up the molecules of ozone that protect Earth's surface from harmful ultraviolet radiation.

Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) are a class of synthetic chemicals used in a number of industrial applications, including refrigeration, air conditioning, and aerosols. First developed in the 1920s, they saw widespread use in industrial applications and consumer goods due to their stability, low toxicity, and non-flammability. However, in the 1970s, scientists discovered that CFCs were contributing to the depletion of the ozone layer. When CFCs are released into the atmosphere, they rise up to the stratosphere and are broken down by UV radiation, releasing chlorine atoms. These chlorine atoms then break up the fragile bonds between the three oxygen atoms that form the compound ozone, thus depleting the ozone layer that protects life from harmful, high-energy sunlight.

These chemicals can last in the stratosphere for hundreds of years – which can not only affect the ozone layer but also the climate.

Since the discovery of their detrimental effects on the ozone layer, their production and use have been phased out. In the late 1980s, the discovery of the Antarctic ozone hole led to global concern and action to limit the production and use of CFCs. The Montreal Protocol, signed in 1987, is an international treaty aimed at phasing out the production and consumption of CFCs and other ozone-depleting substances. The success of the Montreal Protocol is evident in the significant reduction of CFC levels in the atmosphere and the gradual restoration of the ozone layer.

Despite this, recent studies have shown that CFC levels are on the rise, posing a threat to the recovery of the ozone layer. A new study published in Nature Geoscience shows that five types of CFCs have been rising rapidly in the past decade. While the Montreal Protocol allows – but doesn't encourage – use of CFCs as an intermediate product in the production of less-damaging hydrofluorocarbons, the rising emission may counteract the positive effects of the Montreal Protocol.

"This shouldn't be happening," Martin Vollmer, an atmospheric chemist at the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology in Dübendorf who helped to analyze data from an international network of CFC monitors, said to Nature Magazine. "We expect the opposite trend, we expect them to slowly go down."

At the moment, the current levels are not threatening the closure of the ozone layer's gap. However, these chemicals can last in the stratosphere for hundreds of years – which can not only affect the ozone layer but also the climate. As potent greenhouse gases, these gases will only contribute to the overall warming of the atmosphere.

Pinpointing the exact origin of these chemicals is difficult since there are no known reactions that would produce CFC-13 as a byproduct.

The researchers focused on only five CFCs in the stratosphere, and they were able to determine the three CFCs, CFC-113a, CFC-114a, and CFC-115, had increased emissions due to their usage in HFCs. The producers of the two other CFCs that are increasing in atmospheric concentration, CFC-13, and CFC-112a, are still a mystery.

The most likely source of the production of these banned compounds is factories in regions with poor regulatory structures. Ian Rae from the University of Melbourne's School of Chemistry told ABC Science that "not all countries are as strict in regulating their industries."

"There's a tendency if you've got an impurity to just let it go," Rae said. "In poorly regulated countries that's what happens — you put it down the drain if you don't want it."

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

While CFC-112a's appearance is assumed to result from the byproduct of a different industrial reaction, scientists can only speculate as to where CFC-13 is originating from. Pinpointing the exact origin of these chemicals is difficult since there are no known reactions that would produce CFC-13 as a byproduct.

For decades, researchers have consistently observed atmospheric levels of CFCs. Typically, the global monitoring system has worked well for stopping polluters, at least in past years when similar issues arose.

Indeed, in 2019, researchers detected unusually high levels of CFC-11 in the atmosphere, which they tracked back to eastern China. Using readings from stations across Eastern Asia in countries such as South Korea and Japan, they were able to pinpoint the source of increased CFC-11 emissions in eastern mainland China, a violation of the Montreal Protocol. Since then, illegal CFC emissions like that began to steadily decrease.

In this new study, researchers say that the release of industrial byproducts like CFC-112a may need to be addressed in a revised version of the Montreal Protocol.

Read more

about the ozone layer and industrial pollutants

Shares