Humans and worms don't appear to have much in common, but a new study demonstrates that we both get the munchies when ingesting weed and weed-like substances. Smoking marijuana or downing a few edibles has a predictable effect on most humans thanks to the drug THC, which is a cannabinoid that triggers feelings of euphoria, enhanced or distorted perception (such as taste or time) and a ravenous appetite known as "the munchies." Even though the last common ancestor between humans and worms lived over 500 million years ago, after which we drifted apart evolutionarily, both species evidently experience something comparable.

The idea to give worms cannabinoids to came to Lockery after Oregon legalized cannabis in 2015.

A new study in the journal Current Biology monitored the feeding behavior of a type of worm called a nematode after being given a naturally produced cannabinoid called anandamide (AEA). Many mammals, including humans, generate anandamide to regulate mood, appetite and many other functions in the body. The name anandamide comes from the Sanskrit word for "bliss," because AEA is implicated in reward circuits in the brain. In other words, it can make you feel good.

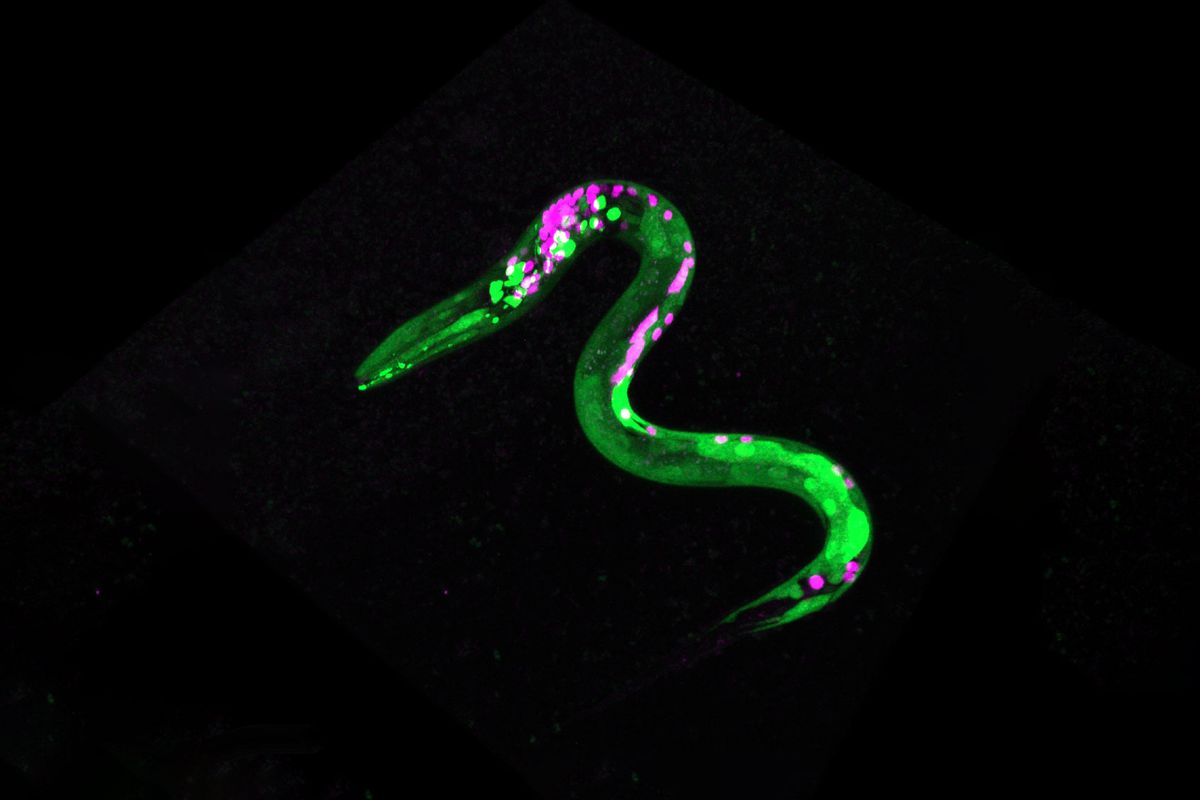

The human brain produces its own drugs, including cannabinoids and even psychedelics, though not typically at levels that really make you feel high. Endocannabinoids like anandamide and 2-AG (2-arachidonoylglycerol) perform critical functions in the body, including regulating appetite. Structurally, AEA and THC are very similar, which is why THC works on the human body at all. When scientists at the University of Oregon's Institute of Neuroscience gave AEA to a nematode called Caenorhabditis elegans, they found that the worms also got the munchies, which reveals something quite fascinating about human evolution.

"Nematodes diverged from the lineage leading to mammals more than 500 million years ago," Professor Shawn Lockery, the study's lead author, said in a statement. "It is truly remarkable that the effects of cannabinoids on appetite are preserved through this length of evolutionary time."

C. elegans are a well-studied organism that is about 1 millimeter in length — not much longer than a sharpened pencil point. They are transparent and typically found in soil. Despite their size and distance from humans on the tree of life, they still have an endocannabinoid system that works like a much more primitive version of our own. Mammals have cannabinoid receptors called CB1 and CB2, whereas C. elegans have a receptor called NPR-19 — which, despite how it sounds, has nothing to do with either public radio nor COVID-19.

Later, Lockery and colleagues genetically modified the C. elegans worms, inserting a human version of the cannabinoid receptor, with similar results.

These nematodes eat the bacteria in decaying plant matter, using a tube called a pharynx, which is a muscular pump that constitutes its throat. Even with rudimentary senses for vision and smell, C. elegans can detect food and even displays preferences for food types. The idea to give worms cannabinoids to came to Lockery after Oregon legalized cannabis in 2015.

"At the time, our laboratory at the University of Oregon was deeply involved in assessing nematode food preferences as part of our research on the neuronal basis of economic decision-making," Lockery said. "In almost literally a 'Friday afternoon experiment' — read: 'let's dump this stuff on to see what happens' — we decided to see if soaking worms in cannabinoids alters existing food preferences. It does, and the paper is the result of many years of follow-up research."

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

In the experiment, which was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Lockery and colleagues first found that giving nematodes AEA made the worms want to eat more, with increased appetite for their favorite foods as well. This was determined by putting the worms into a T-shaped maze, with different bacterial food sources on either end. The "stoned" worms went straight for their preferred meal.

This is similar to humans who get the munchies: we don't just crave food, we want anything and everything high in sugar and fat. Later, Lockery and colleagues genetically modified the C. elegans worms, inserting a human version of the cannabinoid receptor, with similar results.

"We found that the sensitivity of one of the main food-detecting olfactory neurons in C. elegans is dramatically altered by cannabinoids," Lockery said. "Upon cannabinoid exposure, it becomes more sensitive to favored food odors and less sensitive to non-favored food odors. This effect helps explain changes in the worm's consumption of food, and it is reminiscent of how THC makes tasty food even tastier in humans."

This is one of the few studies that looks at how cannabinoids affect invertebrates and their feeding behavior. Intriguingly, this relationship seems to have reversed sometime along the evolutionary timeline. In other words, cannabinoids in some invertebrates cause the opposite of the munchies.

"Early in evolution, the predominant effect may have been feeding inhibition. For example, cannabinoid exposure shortens bouts of feeding in Hydra [a tiny jellyfish-like creature] and larvae of the tobacco hornworm moth Manduca sexta prefer to eat leaves containing lower rather than higher concentrations of the phytocannabinoid cannabidiol [CBD]," Lockery and colleagues wrote in the paper.

Fruit flies also experience appetite suppression when exposed to cannabinoids.

"The picture that emerges is that whereas, the original response to cannabinoids may have been feeding suppression, the opposite effect arose through evolution, sometimes in the same organism," the paper continues. The nematode C. elegans "exhibits both increases and decreases in consummatory and appetitive responses under the influence of cannabinoids."

Next, Lockery's lab hopes to give nematodes psychedelic drugs to see how they react. While on the surface this study sounds somewhat ridiculous — a group of serious scientists essentially getting worms stoned — it actually reveals something quite striking about human evolution. We have a system in us that tells us to gorge on high calorie food when stimulated, but this isn't a recent development, evolutionarily speaking. Mother Nature built the endocannabinoid system over half a billion years ago, and it has benefitted animals all the way to our own present.

Shares