“The residents of Dogville were good, honest folks, and they liked their township,” narrator John Hurt says in a voice of sequins and gravel without betraying the irony art film imp Lars von Trier wags in his audience’s face.

The world that “Dogville” was so pessimistic about two decades ago is now just another day.

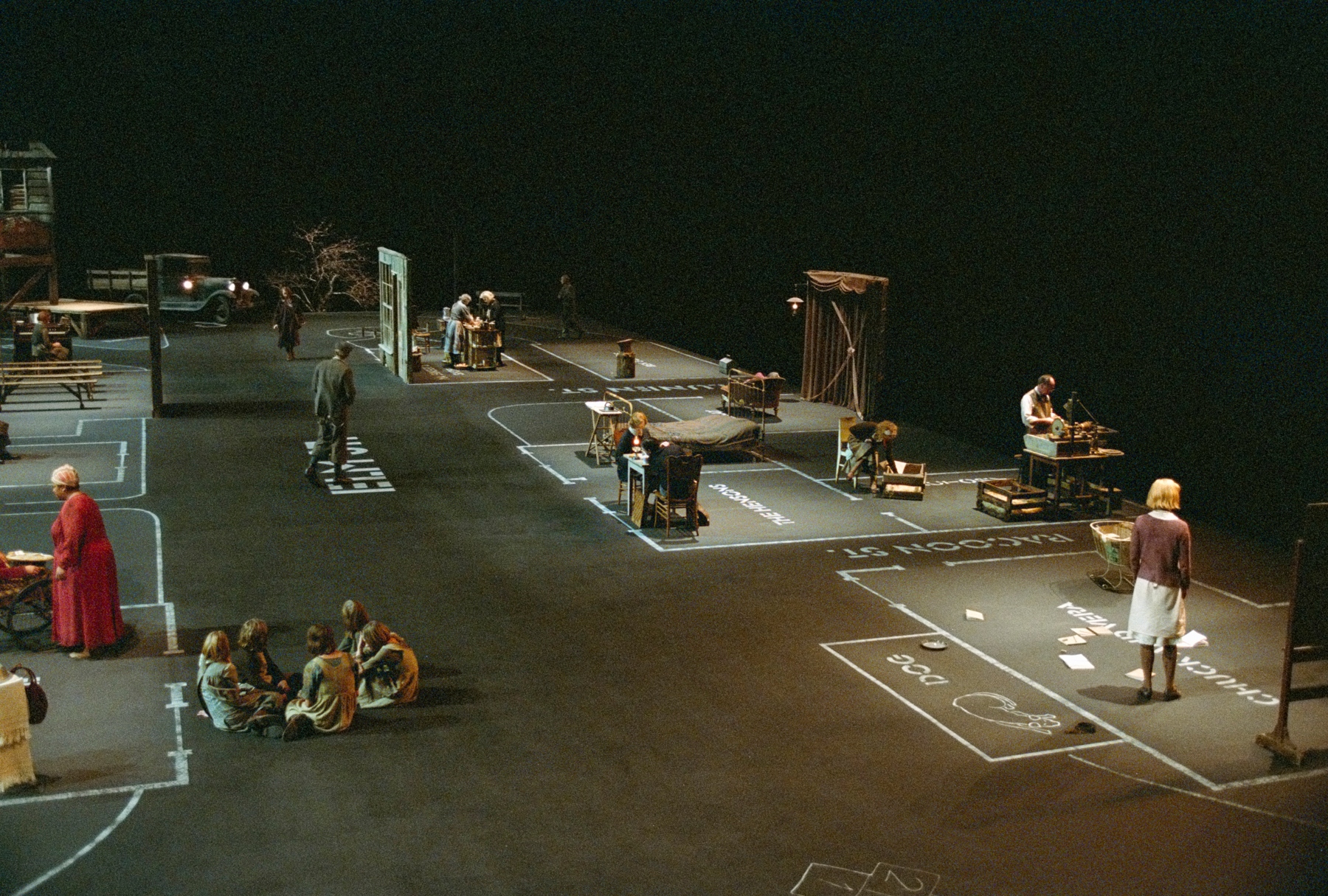

As Hurt describes with sincerity this small hamlet tucked away in the “Rocky Mountains in the US of A,” we stare from above like a god ready to whip out a magnifying glass to track the trail of his little ants. This little town of Dogville has been stripped to its barest parts, just chalk outlines on a black stage with occasional pieces of furniture to suggest home life, community, something bigger than or as small as themselves.

“Good” and “honest” is put to the test by the Danish filmmaker in his visceral, gorgeously alienating “Dogville,” which celebrates its 20th anniversary with a 4K restoration from cinephile-ready streaming site MUBI. When the film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, the New York Times’ AO Scott described “Dogville” as a movie that “mocks your emotional expectations with a teasing ambiguity” and “nose-thumbing expression of this Danish director’s misanthropy . . . relentlessly true to its hateful vision, depicting as a lie the ideal of embracing human community.” Accusations of “misanthropy” were even thrown at the film by Salon’s own Charles Taylor in 2004. Well known for his bruising portraits of people gone wrong who may or may not find salvation through other means in movies like “Breaking the Waves” and the Bjork-starring “Dancer in the Dark,” “Dogville,” with its three-hour runtime and ironic avant-garde stylism felt like an even bolder, nastier jibe from international cinema’s vicious jester.

But the world that “Dogville” was so pessimistic about two decades ago is now just another day. The promise of liberty and freedom are becoming both charged weapons for the right to use and illusions for the left to lose hope in. There is increasing legislation against transgender people thinly veiled as drag bans, the backlash against trans influencer Dylan Mulvaney’s partnerships, increasing police budgets, exponential growth in anti-abortion legislation, and irrevocable effects of climate change amplified by governmental apathy’s cruelties growing untenable and its people in power not yet satiated by how much they wield. “Dogville” was small, but America still foams at the mouth.

Paul Bettany and Nicole Kidman in “Dogville”, directed by Lars von Trier, Sweden, 2002 (Rolf Konow/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images)Despite the formal adventurism from the director, “Dogville” sprawls itself out like a novel, chapter headings and all, detailing this small town community’s decisions when the fur-wearing runaway named Grace (Nicole Kidman) needs a place to stay. Depending upon the democratic process, led by Paul Bettany, they decide to protect her, Grace agreeing to earn her keep while there. But as the police and the men who are after her grow nearer, the townspeople’s perceived sense of threat grows larger, and the demands they make of Grace become increasingly cruel and sadistic. All the while, Grace withstands their brutality, under the belief that they are, in spite of everything, good and honest people.

Paul Bettany and Nicole Kidman in “Dogville”, directed by Lars von Trier, Sweden, 2002 (Rolf Konow/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images)Despite the formal adventurism from the director, “Dogville” sprawls itself out like a novel, chapter headings and all, detailing this small town community’s decisions when the fur-wearing runaway named Grace (Nicole Kidman) needs a place to stay. Depending upon the democratic process, led by Paul Bettany, they decide to protect her, Grace agreeing to earn her keep while there. But as the police and the men who are after her grow nearer, the townspeople’s perceived sense of threat grows larger, and the demands they make of Grace become increasingly cruel and sadistic. All the while, Grace withstands their brutality, under the belief that they are, in spite of everything, good and honest people.

Are the residents of Dogville good because they — the pseudo-intellectual and ineffectual Thomas Edison (Bettany), proud mother Vera (Patricia Clarkson) and flirtatious Liz (Chloe Sevigny), among others — think they’re good? Are they good because an opportune moment of someone else’s desperation — beautiful fugitive Grace — presented itself and can thus flatter their image of themselves as good and honest?

In the real world, hope feels more and more distant as the supposed American virtues of tolerance are either weaponized to justify bigotry and oppression or disposed of altogether in nihilistic glee.

Von Trier paints a stark portrait of power imbalance and both its absurdity and material damage: these little townspeople, who don’t even have a full set to work in, still wield an immense amount of control over the life of one person against whom the deck is stacked. She is reliant on these people for safety; they are the safe haven she needs. But, though Grace is American, that she is routinely bullied and exploited over the course of the film, made to feel grateful for her safety, brings to mind ongoing conversation around the abuse of asylum seekers in the United States.

Through Kidman’s sheer force of nature, she transforms Grace, a character whose function is ultimately to unearth these residents’ hypocrisy, into something more than just a symbol or mechanism of von Trier’s ideological fascinations.

Though the production of the film was turbulent, Kidman imbues a diamond-like complexity to Grace, who, at first conceding to doing favors to the townfolk as compensation for their protection, becomes the object of constant (sexual) abuse and exploitation. Yet, before the end, she believes in these people’s goodness. Whether it is because they are actually good, or because they have told her that, or because she needs something to believe in.

Stellan Skarsgard and Nicole Kidman on the set of “Dogville”Directed by Lars von Trier, Sweden, 2002 (Rolf Konow/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images)Audiences, while making the exhilarating trudge through “Dogville’s” confrontational approach, may extend their sympathies to Grace’s feelings about the inhabitants of her hideout. We believe in her, if not her belief that the people around her are as moral as they claim. But do those contradictory feelings not also mirror our (that being those who live in the United States, at least) ambivalence about the seemingly ceaseless descent into a social and political landscape of abuse, exploitation and acceleration into nothingness? In the real world, hope feels more and more distant as the supposed American virtues of tolerance are either weaponized to justify bigotry and oppression or disposed of altogether in nihilistic glee. There aren’t chalk lines on a bare platform in America, but there are maps of red and blue, graphs of redlining and policy based inequity.

Stellan Skarsgard and Nicole Kidman on the set of “Dogville”Directed by Lars von Trier, Sweden, 2002 (Rolf Konow/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images)Audiences, while making the exhilarating trudge through “Dogville’s” confrontational approach, may extend their sympathies to Grace’s feelings about the inhabitants of her hideout. We believe in her, if not her belief that the people around her are as moral as they claim. But do those contradictory feelings not also mirror our (that being those who live in the United States, at least) ambivalence about the seemingly ceaseless descent into a social and political landscape of abuse, exploitation and acceleration into nothingness? In the real world, hope feels more and more distant as the supposed American virtues of tolerance are either weaponized to justify bigotry and oppression or disposed of altogether in nihilistic glee. There aren’t chalk lines on a bare platform in America, but there are maps of red and blue, graphs of redlining and policy based inequity.

Taking away the ornamentation of elaborate set changes and interiors pulls into focus the people and their actions. There is an immediacy to the way they treat Grace, their self-satisfied way of including her, like on the Fourth of July, when it’s convenient and safe to do so. Liz starts to have fun gossiping with Grace – finally a new, younger woman in town. But the moment she sees Grace as a threat, possibly taking away Tom from her, her tone changes. She lumps in Grace’s sincere affections for Tom with the way Chuck (Stellen Skarsgaard) has been raping the refugee, as if they are the same thing. Grace’s dynamics with everyone begin to sour when they believe she owes them more and more, even as she receives less and less protection. Rushing to an appointment, she walks through gooseberry bushes, only to be scolded by Ma Ginger on the grounds that she “hasn’t lived here as long.” The town of Dogville displays the niceties of burgeoning trust as she does tasks for them, the messaging being that she owes them.

Yet Grace never loses hope. Almost. Have we?

It’s often Tom that relays these demands to her. By way of a self-congratulatory democratic process, they vote on whether to protect her, whether it’s in their best interest to care for another person in need. Gradually, their self-interest veiled in the form of suspicion and protection “for the children” starts to emerge. Grace, despite all she does for them, becomes an object of this tiny culture war. In a sham farce of the democratic process, she finds out her fate through bell tower gongs. As they strip her rights and humanity away, her life still hangs in the balance of those gongs, at least giving her a place to sleep. Even if, by the end, she has a tire chained to her leg and a bell around her neck. It’s like watching the last glimmers of a promise flicker, not yet extinguished, but clawed through like legislation that once protected abortion rights.

Nicole Kidman in “Dogville”, directed by Lars von Trier, Sweden, 2002 (Photo by Rolf Konow/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images) (Rolf Konow/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images)A glamorous white lady though she may be, the people of Dogville still have their own backs to look out for. And, from the point of view of someone who’s headed downward on the economic mobility rollercoaster, Grace will take what she can get, even if it means being blackmailed by a petulant child, being felt up by a blind man, or being manipulated by anyone else in town. But these scenes between Tom and Grace, which morph over time, focus on an intimacy and become a more direct test of just how “good” and “honest” he is. With nothing but a void behind them, will you believe what he says? About what’s best for him, for Grace, for the town . . . for the country?

Nicole Kidman in “Dogville”, directed by Lars von Trier, Sweden, 2002 (Photo by Rolf Konow/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images) (Rolf Konow/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images)A glamorous white lady though she may be, the people of Dogville still have their own backs to look out for. And, from the point of view of someone who’s headed downward on the economic mobility rollercoaster, Grace will take what she can get, even if it means being blackmailed by a petulant child, being felt up by a blind man, or being manipulated by anyone else in town. But these scenes between Tom and Grace, which morph over time, focus on an intimacy and become a more direct test of just how “good” and “honest” he is. With nothing but a void behind them, will you believe what he says? About what’s best for him, for Grace, for the town . . . for the country?

The two are ostensibly a romantic pair, the one who will fight for her and the woman who is swept up by his upstanding devotion to virtue, goodness, honesty. But his intentions sour over time, the power too good to relinquish. We’ve seen that before, a populist for whom the chance to sway the roar of a crowd, no matter how large or small, means more than the actual safety of anyone. But Tom isn’t so much a Donald Trump character; he doesn’t really have the same unhinged ability to find the spectacle of a rally. Rather, he’s snake-like, masquerading his barbarism in faux-philosophical inquiry. He’s like a Jordan Peterson, soft-spoken, promising a new future for men who he thinks has been marginalized by the culture, yet certain that his impression of meekness will help him garner the most power.

Yet Grace never loses hope. Almost. Have we?

In the 20 years since “Dogville” premiered at Cannes, large swaths of the world have swung violently right. But given that von Trier’s film takes place in the United States — one-third of an as-yet incomplete trilogy called “USA — Land of Opportunities” which was followed by “Manderlay” in 2005 and was supposed to end with “Wa$hington” — makes the movie feel a bit more like, if not prophecy, then at least like sign of things to come. A nation that thrives on an image, well-kept, that people can live as they like with their rights to do so protected constitutionally, in addition to optically. However, that is not so, at least not so simply put.

Nicole Kidman in “Dogville”, directed by Lars von Trier, Sweden, 2002 (Rolf Konow/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images)But “Dogville” takes place in the 1930s. It is a vein-bursting elaboration upon Thorton Wilder’s excavation of small town ennui. It is not a prophecy or an omen of what’s to come. It is a portrait of what America has always been: a country whose mythology is predicated on values and beliefs which it makes available conditionally. For von Trier, ironically a man who’s never stepped foot in the States, he believes the Great American Experiment nearly failed before it began.

Nicole Kidman in “Dogville”, directed by Lars von Trier, Sweden, 2002 (Rolf Konow/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images)But “Dogville” takes place in the 1930s. It is a vein-bursting elaboration upon Thorton Wilder’s excavation of small town ennui. It is not a prophecy or an omen of what’s to come. It is a portrait of what America has always been: a country whose mythology is predicated on values and beliefs which it makes available conditionally. For von Trier, ironically a man who’s never stepped foot in the States, he believes the Great American Experiment nearly failed before it began.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Even if von Trier’s assessment of America’s broken promises was evident upon the film’s release, the culture in which we are able to recognize and engage with those critiques has changed. This information and the ways it can be an analog or a refraction of an American reality may not be new, but 20 years on it’s perhaps easier to realize how visceral it all is. That the juxtaposition between the experimentation in its setup and the brazenness in the characters’ and story’s incendiary satire has now reached a point where that dissonance is simply an everyday truth.

The power of Grace is both in her unrelenting hope when it looks like there should not be any left . . . and in her channeling her own desire for retribution against a system that has tried to dehumanize her. Grace walked into a land where things, places and names are written out, to signify in lieu of embodying that goodness and honesty. With the real world’s cruelties growing untenable and its people in power not yet satiated by how much they wield, one wonders when someone, anyone who feels the brunt of it, will do the same. We want to believe that there’s good, and there is, but it’s not only Dogville that has shown its teeth.

Read more

about this topic