Martian dust seems to have claimed another victim: China confirmed it is unable to reestablish contact with its Zhurong rover, which has been scraping around in the dirt of the Red Planet since it landed there on May 14, 2021. Approximately one year later, it entered hibernation in order to brave the harsh Martian winter and its relative lack of sunlight. But the 530 pound (240 kilogram) rover hasn't woken up, missing its December 26 deadline to send a signal back to Earth. It's been quiet ever since.

At the end of April, Beijing finally admitted that the Chinese rover was dead, likely due to accumulations of dust on its solar panels. It's a shame, because even though Zhurong far outlasted its planned life of 93 Earth days (it instead lasted an impressive 356), it made some impressive discoveries. Recently, it was announced that Zhurong had detected evidence that liquid water was flowing on Mars within the last 1.4 million years, which is relatively recent in geologic terms.

Zhurong joins a number of other Mars robots that are now inoperative, including NASA's Spirit and Opportunity rovers, which sputtered out after six years and 77 days and 14 years and 138 days, respectively. Moreover, failing space probes have been in the news lately — including the Japanese robotic spacecraft company ispace Inc. which lost contact with its probe after it likely crashed onto the Moon's surface in late April.

In contrast, NASA recently announced a plan to keep its Voyager 2 spacecraft, which was first launched more than 45 years ago, up and running for another three years at least, by dipping into its reserve fuel. How has a space probe launched in the '70s outlived so many more recent space exploration robots? The simple answer is that not all probes are equal, and failure is often just a roll of the dice away.

But looking back at the oldest, still running space probes can tell us something about the future of space exploration. We've put together a list of the longest-living space probes that are still actively sending data back.

A caveat: there are a few probes that are suspected to still be functional, yet we either don't know their location in deep space or mission control simply isn't attempting to contact them; those are not included here.

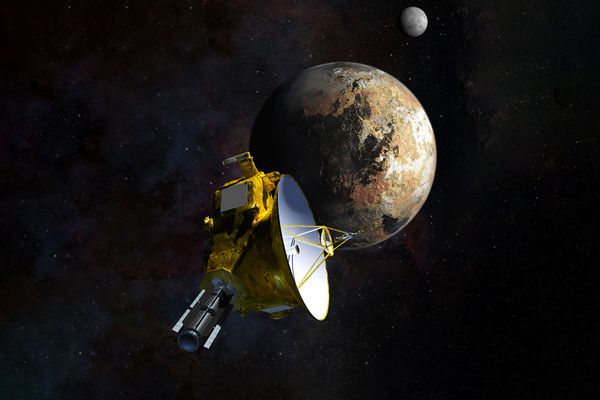

NASA's New Horizons Spacecraft Begins First Stages of Pluto Encounter (NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute)

NASA's New Horizons Spacecraft Begins First Stages of Pluto Encounter (NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute)Launched in 2006, NASA's New Horizons primary mission was to get a closeup of Pluto, which it completed in July 2015. Being the first-ever space probe to visit the dwarf planet, New Horizons provided stunning pictures of Pluto's red and white surface, including Tombaugh Regio, a light-colored topographical swath in the shape of a heart. Studying this revealed that Pluto is most likely geologically active and has the only active glaciers anywhere outside Earth. (At least, until we melt them all.)

After flying by Pluto, New Horizons kept going and become one of five human-made objects to escape the Solar System and enter the space between stars. It's still running and now studying strange objects in the Kuiper belt, a disc of material that circles the Solar System, sort of like the asteroid belt. But the objects here are made of much different material.

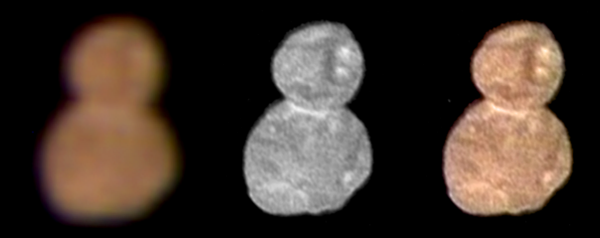

New Horizons got a close peek at one of them, dubbed 486958 Arrokoth, which is the farthest and most primitive object in the Solar System visited by a spacecraft. Named for the Powhatan word for "cloud," Arrokoth is a double-lobed object that resembles a squished snowman. It is thought that the outer solar system was mostly filled with objects like Arrokoth when it formed more than 4.5 billion years ago.

The first color image of 486958 Arrokoth, taken at a distance of 85,000 miles (137,000 kilometers) at 4:08 Universal Time on January 1, 2019, highlights its reddish surface. (NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute)

The first color image of 486958 Arrokoth, taken at a distance of 85,000 miles (137,000 kilometers) at 4:08 Universal Time on January 1, 2019, highlights its reddish surface. (NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute)

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

Artist's rendering, from NASA, of the 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft, in mission configuration (NASA/Wiki Commons)

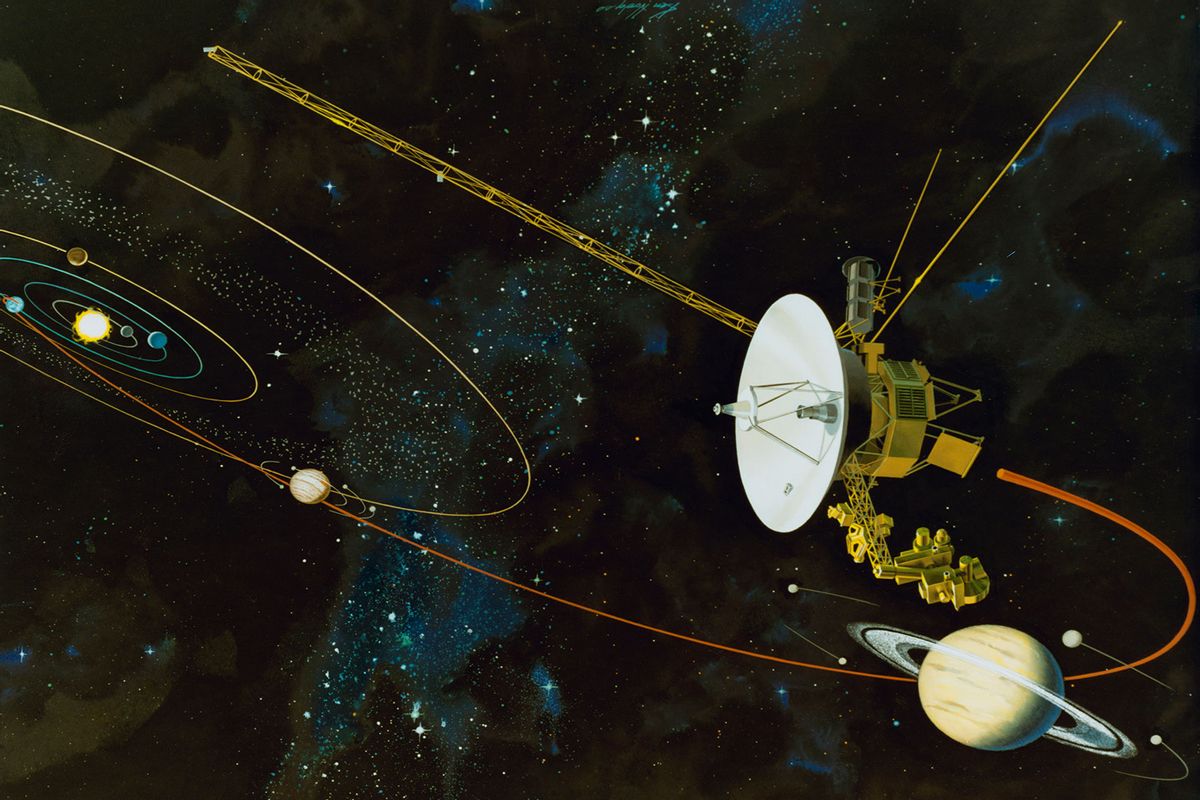

Artist's rendering, from NASA, of the 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft, in mission configuration (NASA/Wiki Commons) Artist's concept of Voyager in flight (NASA/JPL/Wiki Commons)

Artist's concept of Voyager in flight (NASA/JPL/Wiki Commons)Both are still operating to this day, despite being approximately 12 billion miles (20 billion kilometers) away. Part of the reason they've lasted so much longer than other probes has to do with how they're powered. The probes use three plutonium dioxide radioisotope thermoelectric generators. These RTGs are a kind of nuclear battery powered using heat from the natural radioactive decay of plutonium-238, making them long-lasting and fully functional even in the cold, dark depths of space.

Like with most highly radioactive substances, RTGs are somewhat controversial, particularly when these devices are launched on rockets, which sometimes explode and rain debris on Earth. For that reason, RTGs are designed in a way so that even if a rocket exploded or a satellite crashed back to Earth, it would be very unlikely to leak or damage anything. RTGs also pose the risk of polluting other regions in the Solar System that may harbor life, including Titan, one of Jupiter's moons — which may be extremely unlikely, but nonetheless, it's a possibility astronomers have to plan for.

Fortunately, the Voyager probes are so far away from any major solar system body that we don't have to worry about that. Rather, the two probes are on an escape trajectory from our solar system. In about 300 years, they will pass through the Oort Cloud, a distant and sparse ring around the sun which astronomers believe is the origin of many comets in the solar system. Eventually, when its nuclear batteries run out of juice for good, it will continue to quietly orbit the center of mass of the Milky Way for eternity.

In the meantime, the probes continue to send back interesting data about the nature of interstellar space, meaning the region beyond the Sun's solar wind. In 2021, Voyager 1 picked up the "hum" of plasma waves in interstellar space, which one scientist at the time described as akin to a "gentle rain."

Shares