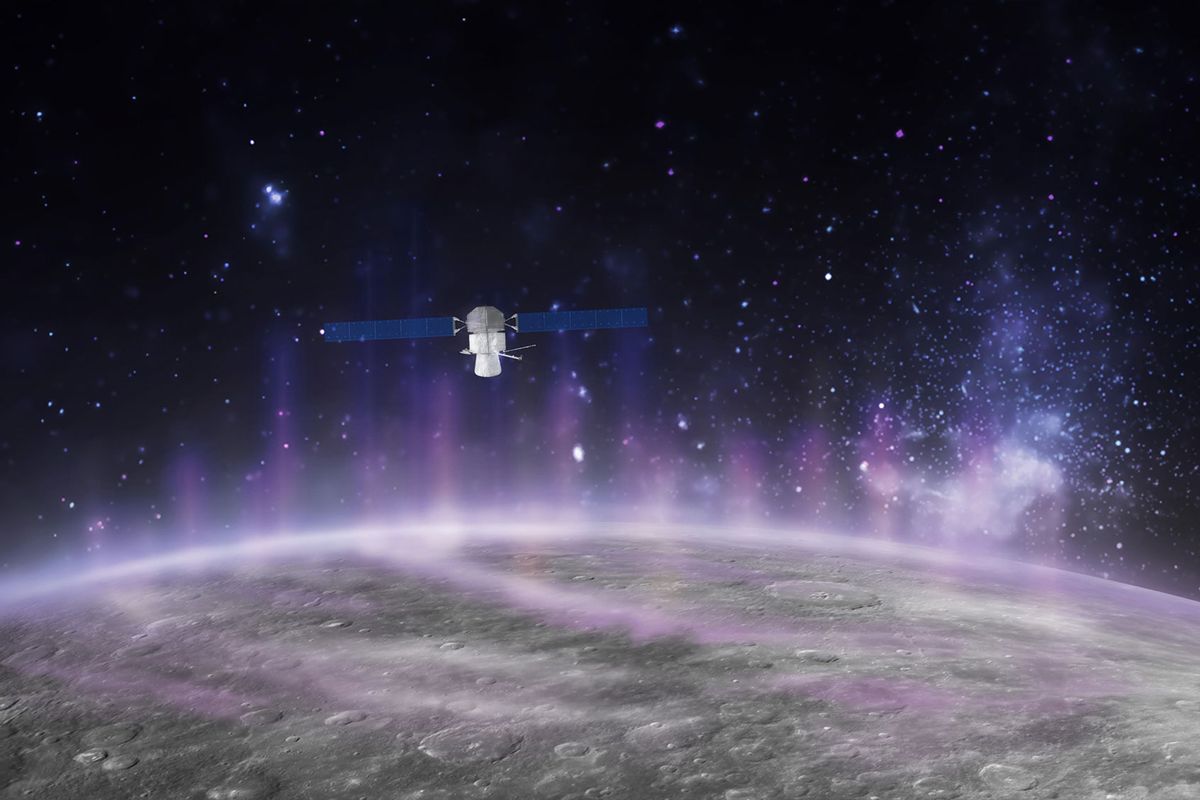

New research in the journal Nature Communications details the weak, atmosphere-like exosphere surrounding the planet Mercury. Enroute to the planet since 2018, the twin spacecraft of the BepiColumbo mission swooped through the innermost rings of our solar system in 2021, flying just 124 miles above the tiny planet closest to the Sun. The endeavor is between the European Space Agency and Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). Thanks to the spacecraft's plasma instruments, astronomers have detected how solar winds (whipping charged particles across the surface of Mercury) create high-pressure conditions in the planet's magnetosphere, unleashing a rain-shower of electrons that coats the planet with X-ray auroras that are invisible to the human eye.

"For the first time, we have witnessed how electrons are accelerated in Mercury's magnetosphere and precipitated onto the planet's surface. While Mercury's magnetosphere is much smaller than Earth's and has a different structure and dynamics, we have confirmation that the mechanism that generates aurorae is the same throughout the Solar System," said JAXA's Sae Aizawa, lead author of the research, said in a statement.

A decade ago, NASA's Messenger mission to Mercury gave humans our closest view of the auroras. But at the time we didn't understand what generated them and the celestial dance wasn't observed directly. Now, however, we know that as dawn rises on Mercury — a spectacle that only occurs approximately once every 59 of our Earth days — a series of plasma processes accelerates the electrons of the planet's magnetosphere, transported from the tail region of the solar winds until they're showered down onto the planet's crater-speckled surface. That's when our fastest celestial sibling, hurtling around the sun at 107,082 miles per hour, its X-ray aurora bursting forth in a dazzling spray of high-powered, invisible energy.

Shares