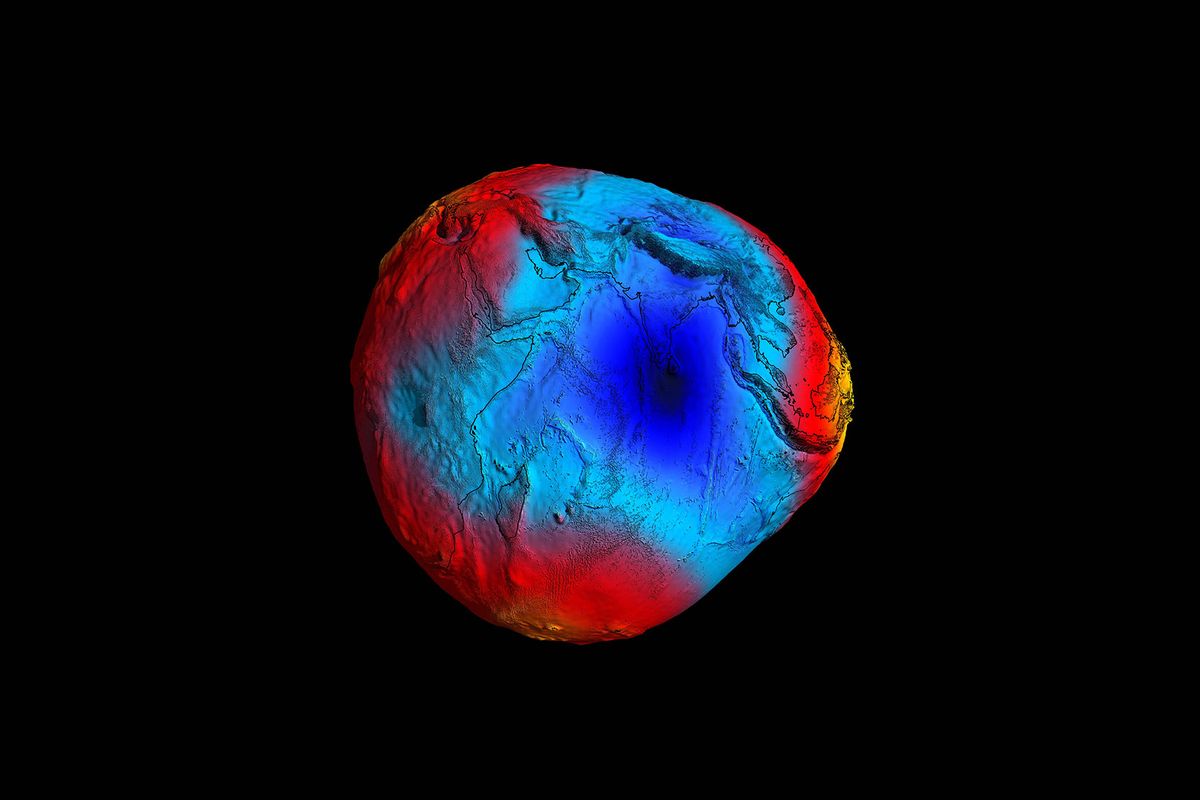

There is a place on Earth where the laws of gravity as we know them do not apply. Officially known as "the Indian Ocean geoid low" (IOGL), it is informally referred to as the Indian Ocean gravity hole. At the IOGL, the sea level dips by a staggering 328 feet (100 meters) and Earth's gravitational pull is weaker. This anomaly has baffled scientists for years — but experts from the Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru, India believe they have solved the puzzle.

It turns out, it all comes down to liquid hot magma.

These plumes, along with the nearby mantle structure, are believed to form the "gravity" hole.

As explained by the scientists' new paper in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, there are "mantle density anomalies" that are not present immediately below the IOGL, but are nevertheless actually there. This is because the Earth is not shaped like a perfect sphere but rather closer to an ellipsoid, with its thickness from the equator being roughly 70,000 feet wider than from the poles.

What's more, because some areas of Earth are more dense than others, they exert different types of gravitational pull on the mass above it. As a result, if all of Earth's ocean existed under gravity without factors like wind and tides, the planet would more closely resemble a geoid: Imagine a golf ball melted to the point where some of its dimples expanded and other collapsed, and you have a good approximation a geoid's appearance.

The new paper hypothesizes there are plumes of magma which exist around the IOGL. These plumes, along with the nearby mantle structure, are believed to form the "gravity" hole because it winds up being the lowest point in that geoid, creating its biggest gravitational anomaly. In the case of the IOGL, this equals a circular depression roughly 1.2 million square miles (3 million square kilometers).

Those plumes in turn seem to have been created during an ancient phase in Earth's history. As the planet's tectonic plates shifted over molten rock 140 million years ago, and as India's land mass collided with the Asian continent, a previously-existing ancient ocean known as Tethys could have disappeared. This in turn would have sent the oceanic plate down in the mantle, catalyzing the creation of the magma plumes.

This is merely a hypothesis, one created after the researchers ran 19 sophisticated computer simulations based on various plausible scenarios involving the Earth's ancient geological history. Though published in a peer-reviewed journal, the hypothesis ultimately remains only as sound as the models themselves. At least one scientist has criticized their paper on that basis: Dr. Alessandro Forte, a professor of geology at the University of Florida in Gainesville, who was not involved with the research. In an interview with CNN, Forte claimed that "the most outstanding problem with the modeling strategy adopted by the authors is that it completely fails to reproduce the powerful mantle dynamic plume that erupted 65 million years ago under the present-day location of Réunion Island."

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

2023 has been full of interesting papers that redefine how human beings examine Earth as a planet.

He added, "The eruption of lava flows that covered half of the Indian subcontinent at this time — producing the celebrated Deccan Traps, one of the largest volcanic features on Earth — have long been attributed to a powerful mantle plume that is completely absent from the model simulation." Forte also claimed the computer simulations did not accurately project the actual shape of Earth as a geoid.

Study coauthor Attreyee Ghosh told CNN in reply that "we do not know with absolute precision what the Earth looked like in the past. The farther back in time you go, the less confidence there is in the models. We cannot take into account each and every possible scenario and we also have to accept the fact that there may be some discrepancies on how the plates moved over time."

Ghosh concluded, "But we believe the overall reason for this low is quite clear."

2023 has been full of interesting papers that redefine how human beings examine Earth as a planet. Last month a study in the scientific journal Geophysical Research Letters found that humans have changed the Earth's axis from too much groundwater extraction. As a result, the True North Pole has shifted at a rate of 4.36 centimeters (or more than 1.7 inches) every year. This is not as surprising as it sounds when scientists consider that between 1993 and 2010 alone, more than 2 trillion tons of groundwater was extracted from the Earth for drinking, irrigation, sanitation and manufacturing.

We need your help to stay independent

Meanwhile, in January a study published in the scientific journal Nature Geoscience revealed that Earth's inner core is currently rotating at a slower rate than the rest of the planet — and may even have hit a temporary "pause." Yet before one conjures up imagines of disaster akin to the 2003 film "The Core," in fact this slowing has only had the most mild effects.

"It has effects on the magnetic field and the Earth's rotation, and perhaps the surface processes and climate," Xiaodong Song, the leading author on the study and a geoscientist at Peking University responsible for pioneering work in 1996 on the inner core, told Salon by email at the time. "It may have a long-term effect (decades and centuries), but the effect on daily life is likely small."

Shares