Climate Connections is a collaboration between Grist and the Associated Press that explores how a changing climate is accelerating the spread of infectious diseases around the world, and how mitigation efforts demand a collective, global response. Read more here.

In 2022, doctors recorded the first confirmed case of tick-borne encephalitis virus acquired in the United Kingdom.

It began with a bike ride.

A 50-year-old man was mountain biking in the North Yorkshire Moors, a national park in England known for its vast expanses of woodland and purple heather. At some point on his ride, at least one black-legged tick burrowed into his skin. Five days later, the mountain biker developed symptoms commonly associated with a viral infection: fatigue, muscle pain, fever.

At first, he seemed to be on the mend, but about a week later, the man began to lose coordination. An MRI scan revealed he had developed encephalitis, or swelling of the brain. He had been infected with tick-borne encephalitis, or TBE, a potentially deadly disease that experts say is spreading into new regions due in large part to global warming.

For the past 30 years, the U.K. has become roughly 1 degree Celsius warmer on average compared to the historical norm. Studies have shown that several tick-borne illnesses are becoming more prevalent because of climate change. Public health officials are particularly concerned about TBE, which is deadlier than more well-known tick diseases such as Lyme due to the way it has quickly jumped from country to country.

Gábor Földvári, an expert at the Center for Ecological Research in Hungary, said the effects of climate change on TBE are unmistakable.

"It's a really common problem that was absent 20 or 30 years ago."

Ticks can't survive more than a couple of days in temperatures below zero, but they're able to persevere in very warm conditions as long as there's enough humidity in the environment. As Earth warms on average and winters become milder, ticks are becoming active earlier in the year. Climate change affects ticks at every stage of their life cycle — egg, six-legged larva, eight-legged nymph, and adult — by extending the length of time ticks actively feed on humans and animals. Even a fraction of a degree of global warming creates more opportunity for ticks to breed and spread disease.

"The number of overwintering ticks is increasing, and in spring there is high activity of ticks," said Gerhard Dobler, a doctor who works at the German Center for Infection Research. "This may increase the contact between infected ticks and humans and cause more disease."

Since the virus was first discovered in the 1930s, it has mainly been found in Europe and parts of Asia, including Siberia and the northern regions of China. The same type of tick carries the disease in these areas, but the virus subtype — of which there are several — varies by region. In places where the virus is endemic, tick bites are the leading cause of encephalitis, though the virus can also be acquired by consuming raw milk from tick-infected cattle. TBE has not been found in the United States, though a few Americans have contracted the virus while traveling in Europe.

According to the World Health Organization, there are between 10,000 and 12,000 cases of the disease in Europe and northern Asia each year. The total number of cases worldwide is likely an undercount, as case counts are unreliable in countries where the population has low awareness of the disease and local health departments are not required to report cases to the government. But experts say there has been a clear uptick since the 1990s, especially in countries where the disease used to be uncommon.

"We see an increasing trend of human cases," Dobler said, citing rising cases in Austria, Germany, Estonia, Latvia, and other European countries.

TBE is not always life-threatening. On average, about 10 percent of infections develop into the severe form of the illness, which often requires hospitalization. Once severe symptoms develop, however, there is no cure for the disease. The death rate among those who develop severe symptoms ranges from 1 to 35 percent, depending on the virus subtype, with the far-eastern subtype being the deadliest. In Europe, for example, 16 deaths were recorded in 2020 out of roughly 3,700 confirmed cases.

Up to half of survivors of severe TBE have lingering neurological problems, such as sleeplessness and aggressiveness. Many infected people are asymptomatic or only develop mild symptoms, Dobler said, so the true caseload could be up to 10 times higher in some regions than reports estimate.

While there are two TBE vaccines in circulation, vaccine uptake is low in regions where the virus is new. Neither vaccine covers all of the three most prevalent subtypes, and a 2020 study called for development of a new vaccine that offers higher protection against the virus. In Austria, for example, the TBE vaccine rate is near 85 percent, Dobler said, and yet the number of human cases continues to trend upward — a sign, in his opinion, of climate change's influence on the disease.

[Read next: Mosquitos are moving to higher elevations — and so is malaria]

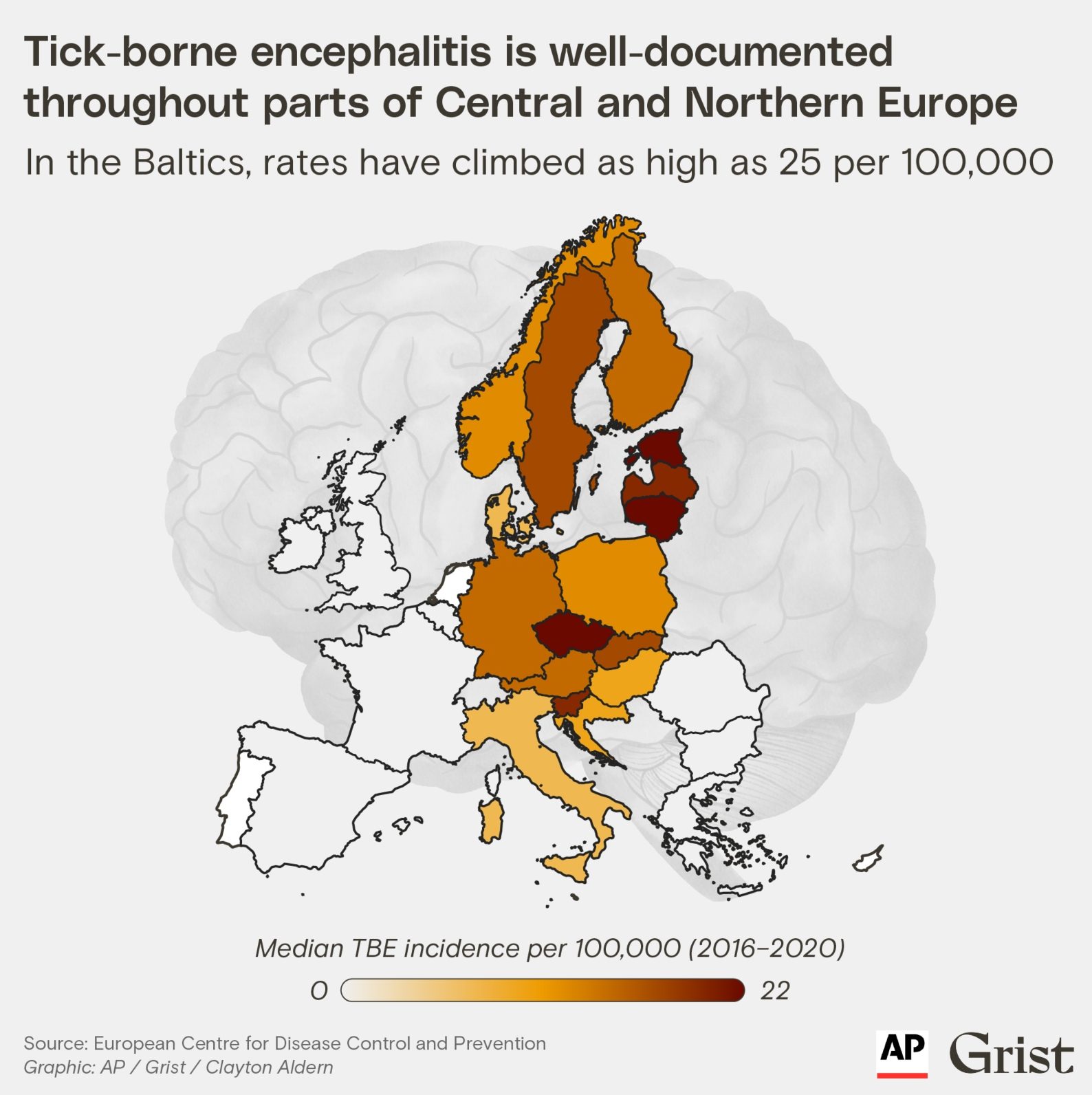

In Central and Northern Europe, where for the past decade average annual temperatures have been roughly 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial times, documented cases of the virus have been rising in recent decades — evidence, some experts say, that rising global temperatures are conducive to more active ticks. The parasitic arachnids are also noted to be moving further north and higher in altitude as formerly inhospitable terrain warms to their preferred temperature range. Northern parts of Russia are a prime example of where TBE-infected ticks have moved in. And some previously tick-free mountains in Germany and Austria are reporting a 20-fold increase in cases over the past 10 years.

The virus's growing shadow across Europe, Asia, and now parts of the United Kingdom throws the dangers of tick-borne disease into sharp relief. The U.K. bicyclist who was the first domestically acquired case of the disease survived his bout with TBE, but the episode serves as a warning to the region: Though the virus is still rare, it may not stay that way for long.

This article originally appeared in Grist at https://grist.org/health/tick-borne-encephalitis-virus-europe-climate-change/.

Grist is a nonprofit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future. Learn more at Grist.org

Shares