Mining the bottom of the ocean for precious metals is a dangerous proposition, given the near-freezing temperatures and crushing pressures, but it's being increasingly optioned by nations and mining companies eager for raw materials like cobalt and nickel. Last week, officials met in Kingston, Jamaica to discuss international regulations for deep sea mining, operations many scientists and policymakers oppose due to the potential harm they can cause to the environment.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), a United Nations-affiliated group, faces pressure to establish rules that protect ecosystems on the ocean floor, many of which are still being investigated. After a "two-year rule" expired earlier in July, the meeting was held as part of negotiations on how nations should proceed with ocean floor mining ventures.

Ultimately, the ISA kicked the can down the road, agreeing to finalize rules for scraping the seafloor for valuable metals by 2025. Although officials did not approve mining operations, they also didn't agree on what process they'd follow should any requests to mine be filed in the meantime. Many are concerned this will open up the possibility that mining for materials on the ocean floor will begin without regulations in place, threatening the creatures that live there.

"From a scientific point of view, one of the things we have emphasized is that there's still such a lack of data — of environmental baselines and responses of ecosystem impacts — to be able to effectively develop rules and regulations related to environmental impact assessments, thresholds of harm, monitoring, and things like that," Beth Orcutt, vice president of Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, told Salon.

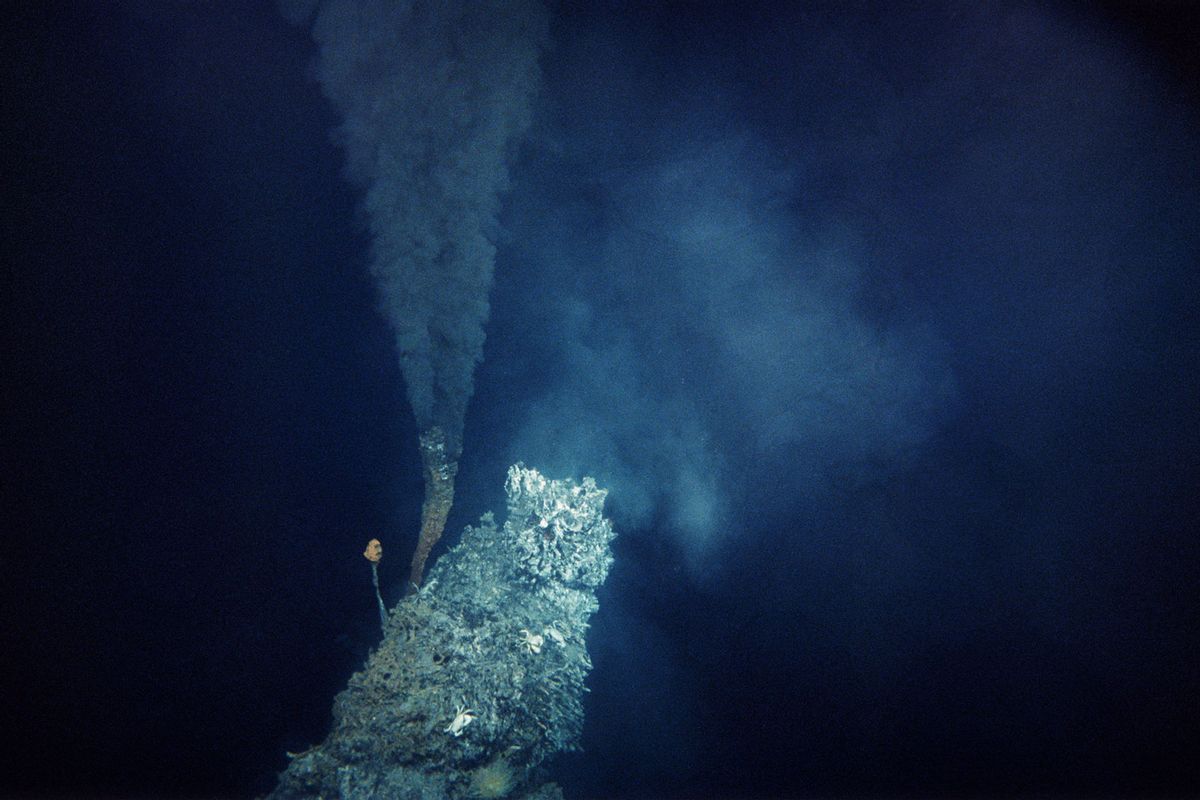

Little is known about the deep sea floor, and what evidence does exist suggests excavating it could damage sensitive marine life.

Those who support deep sea mining argue the practice is a means to shift toward renewable energy, as much of the cobalt and nickel recovered in these operations could be used for battery production in electric car manufacturing. Currently, nearly 70 percent of the world's supply of cobalt is sourced from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), but operations there have come under scrutiny for enacting child labor and inhumane working conditions. Nauru, an island nation in the Pacific Ocean, gave the U.N. an ultimatum two years ago to finalize regulations.

As reported by The Guardian, Nauru's president, Russ Kun, told delegates, "We have a window of opportunity to support the development of a sector that Nauru considers has the potential to help accelerate our energy transition to combat climate change."

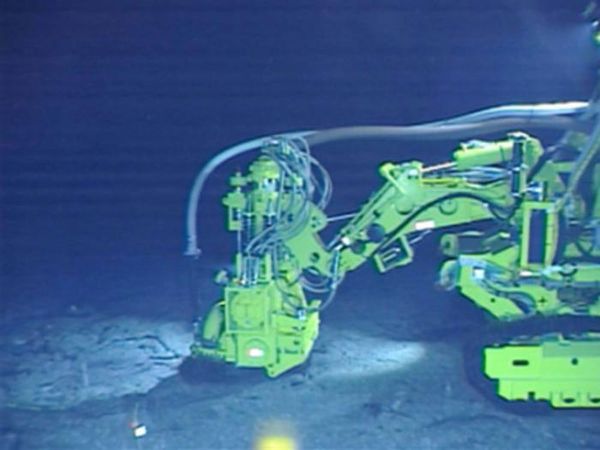

Takuyo-Daigo Seamount deep-sea mining machinery (Photo by Travis Washburn)In 2021, more than 700 scientists and policy experts signed an open letter asking for a moratorium on the extraction of materials from the seafloor. A coalition of Indigenous nations in the Pacific also came forward to formally oppose deep sea mining and over a dozen countries have called to pause or completely halt mining operations until more data is available. Little is known about the deep sea floor, and what evidence does exist suggests excavating it could damage sensitive marine life.

Takuyo-Daigo Seamount deep-sea mining machinery (Photo by Travis Washburn)In 2021, more than 700 scientists and policy experts signed an open letter asking for a moratorium on the extraction of materials from the seafloor. A coalition of Indigenous nations in the Pacific also came forward to formally oppose deep sea mining and over a dozen countries have called to pause or completely halt mining operations until more data is available. Little is known about the deep sea floor, and what evidence does exist suggests excavating it could damage sensitive marine life.

This month, a study in the journal Current Biology analyzed deep sea mining operations in Japan, finding that even small operations could seriously disrupt deep sea dwellers. Although the mining operation lasted just two hours, fish, eels, and shrimp started disappearing from the zone shortly thereafter. Thirteen months later, populations of these kinds of mobile deep sea dwellers, known as swimming benthos, had dropped by 43 percent in the mining location and 56 percent in adjacent areas surrounding the site.

In 2021, more than 700 scientists and policy experts signed an open letter asking for a moratorium on the extraction of materials from the seafloor.

There is no way to mine without completely destroying the ocean floor from which resources are extracted, said study author Travis Washburn, who works with the Geological Survey of Japan. But this study shows the extent of the impact reaches beyond the primary mining zone and into what is called the area of deposition.

"We have to have controls, areas where there is preservation, where there is no mining," Washburn told Salon. "Even if we choose places that are somewhat farther away, it makes it harder to find an area that is not impacted at all."

Plans for deep sea mining are largely concentrated in the 1.7 million square mile region known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) in the Pacific between Hawaii and Mexico. In May, scientists calculated the discovery of more than 5,000 new species in the region, from Psychropotes longicauda, nicknamed the "gummy squirrel," to Elpidiidae, a part of the family of deep sea cucumbers. Nearly all species identified were unique to the zone, and over 90 percent were new to science. Many still do not even have names.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

Unmoving animals like sponges and corals have previously been thought to have been the most susceptible to harm from human activity on the ocean floor, given they can't escape the impacts of mining, Washburn said. But this study showed that swimmers could be impacted too.

"They're not dying from a plume. They're not getting chopped up — they're swimming away," Washburn said. "They're leaving the area and that could impact everything. They perform a lot of things."

Noise associated with scraping the ocean floor has been linked to disruptions in marine life ecosystems in the CCZ. But in Washburn's research, the operation only lasted a couple of hours, so he hypothesized that what instead caused swimming animals to abandon the site was a lack of food. Typically, deep sea dwellers feed on substances that fall from the surface level and sink down. But mining kicks up debris and rock from below the sea bottom that might cover any food that was available, he said.

We need your help to stay independent

Another study that reviewed the effect of a disturbance to the sea floor in 1989 found the ecosystem still hadn't returned to equilibrium nearly 30 years after the fact. Some researchers estimate another decade of research is needed to understand each type of ecosystem on the ocean floor. But with pressure on the ISA to finalize regulations by 2025, scientists are collaborating with the agency to comb through what data exists to come up with thresholds for harm, Orcutt said.

"The concern is the impacts would be permanent," Orcutt said.

Shares