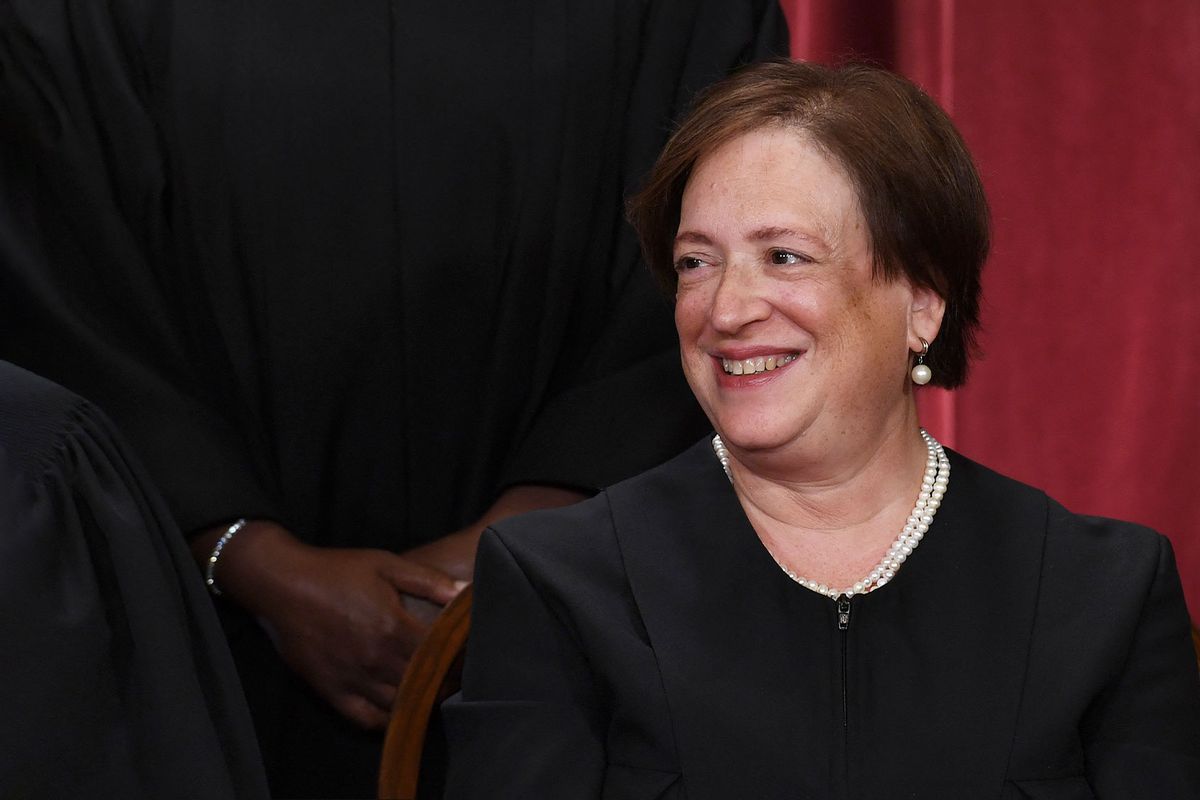

Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan on Thursday threw her opinion into the heated debate over the highest court's ethics, asserting that Congress has broad powers to check the Supreme Court despite her conservative colleague's claim that such action would violate the separation of powers outlined in the Constitution.

According to Politico, Kagan made her comments at the Ninth Circuit Judicial Conference in Portland, Oregon, just days after the Senate Judiciary Committee advanced a bill requiring the court to establish an ethics code and a method to enforce it in response to recent controversies around conservative Justice Clarence Thomas' luxury travel and relationship with GOP megadonor Harlan Crow.

"It just can't be that the court is the only institution that somehow is not subject to checks and balances from anybody else. We're not imperial," Kagan told the audience of judges and lawyers. "Can Congress do various things to regulate the Supreme Court? I think the answer is: yes."

She clarified that she was not responding to Justice Samuel Alito's remarks in an interview last month that Congress would be violating the separation of powers if legislators sought to create ethics and recusal policies for the high court.

"Congress did not create the Supreme Court," Alito told The Wall Street Journal. "No provision in the Constitution gives them the authority to regulate the Supreme Court — period."

Kagan said she was unsure precisely what question Alito was asked and suggested that his statement could not have been as far-reaching as it seemed because the Constitution allows Congress to determine the kinds of cases the Supreme Court can hear.

"Of course, Congress can regulate various aspects of what the Supreme Court does," said Kagan, who joined the court in 2010 after being nominated by President Barack Obama. "Congress funds the Supreme Court. Congress historically has made changes to the court's structure and composition. Congress has made changes to the court's appellate jurisdiction."

She also quickly added that this provision does not mean Congress could work to dictate the outcome of specific cases.

"Can Congress do anything it wants? Well, no," she said. "There are limits here, no doubt."

Kagan expressed reluctance to elaborate on her stance on grounds that the court could someday take on a case in which it is asked to assess those limits. She added that she didn't want to "jawbone it" while Congress is considering legislation although the bill appears to have almost no chance of clearing the full Senate or being taken up by the House.

However, Kagan explained she would prefer to see the Supreme Court work to defuse the current controversies surrounding it by taking its own steps to address ethics concerns. She became the first justice to publicly confirm the widely held suspicions that the justices are at odds on the matter.

"It's not a secret for me to say that we have been discussing this issue, and it won't be a surprise to know that the nine of us have a diversity about this and most things. We're nine freethinking individuals," she said.

We need your help to stay independent

"Regardless of what Congress does, the court can do stuff, you know?" Kagan said. "We could decide to adopt a code of conduct of our own that either follows or decides in certain instances not to follow the standard codes of conduct … that would remove this question of what Congress can do. … I hope that we will make some progress in this area."

During her Thursday remarks, Kagan's approach was more yielding to her conservative colleagues than in a previous flurry of seemingly frustrated comments following the court's 5-4 vote to overturn the federal constitutional right to abortion last June. In her first public comments, since the court ended its most recent term over a month ago, Kagan reiterated her past criticism, suggesting that her colleagues were at times ruling along their policy preferences. She cited rulings from this term curtailing the government's regulatory power over wetlands and striking down President Joe Biden's student debt relief plan.

It's important for the Supreme Court "to act like a court … mostly it means acting with restraint and acting with a sense that you are not the king of the world and you do not get to make policy judgments for the American people," Kagan said.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

She also stressed the importance of the justices reaching an agreement when possible.

"I do believe very strongly in working strenuously to achieve consensus," she said. "I would rather decide less and have greater consensus than decide more with division. … I like to search for what might be thought of as principled compromises. Some compromises you can't make, but some compromises you can."

In the court's latest term, the conservative majority didn't always vote along ideological lines in politically contentious cases. Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh voted alongside the tribunal's three liberals in a redistricting case from Alabama, dismissing efforts to skirt legal requirements to create or maintain districts that provide minority voters with a strong chance of electing their desired candidates.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett also joined Roberts, Kavanaugh and the liberals in shutting down an expansive claim that the Constitution grants state legislatures far-reaching authority over election laws, practices and disputes with little input from governors and state courts.

Despite their compromises, the court's shift to the right is clear. The decisions for three of the most highly contentious cases of the most recent term coincided with the court's 6-3 ideological split. The liberal defeats — all decided on the final week decisions were released — pertained to cases overturning race-based affirmative action in college admissions, striking down Biden's $400 billion student debt relief plan, and establishing business' rights to deny some kinds of services to LGBTQ people.

"Some years are better than other years," Kagan said last year while reflecting on the term in which the court ruled on abortion. "Time will tell whether this is a court that can get back … to finding common ground."

Shares