To build a solar farm, one begins with a lot of sand. Thousands of grains are heated and purified into crystalline silicon, forming reflective silvery stones that are cut and shaped into recognizable solar panels. Once ordered into neat rows in solar farms, the blankets of panels will attract certain species and repel others. In 2010, scientists discovered some water insects like to lay eggs around these structures, perhaps because solar panels mirror the reflective nature of water where they normally spawn.

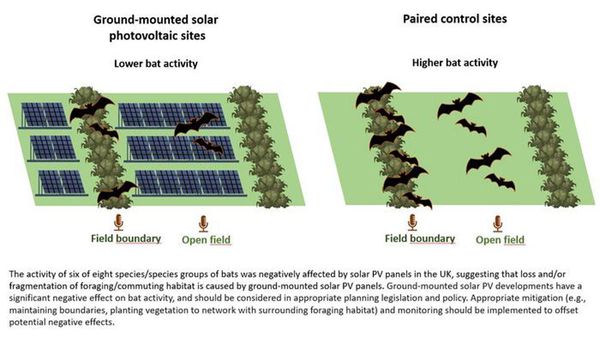

But other animals, like bats, seem to not want to touch solar farms with a 10-foot pole, at least according to a study published this week in the Journal of Applied Ecology. Among 19 solar farms studied in southwest England, bat activity for six out of eight species observed was halved among farms' peripheries and reduced by two-thirds at their center compared to control farms without solar panels, said study author Gareth Jones, Ph.D., a professor of biological sciences at the University of Bristol in England.

"Bats are important indicators of ecosystem health and provide valuable services such as suppression of insect pests," Jones told Salon in an email. "The findings show that solar farms reduce bat activity, and that mitigation is necessary to offset this."

"We know little about how bat populations are affected by solar farms, if at all," he added.

"The findings show that solar farms reduce bat activity, and that mitigation is necessary to offset this."

President Biden set the ambitious goal of transitioning to net zero emissions by 2050, investing in renewable energy instead of fossil fuels in order to slow global warming. Solar photovoltaic energy, which was the type of solar energy measured in the study, is the "fastest-growing source of renewable energy globally," predicted to overtake natural gas by 2026 and coal by 2027, Jones said. As a cheaper and more efficient energy source, renewables can offset global warming — but they aren't without their own environmental impacts.

Illustration showing effect of solar farming on bat activity (Lizy Tinsley)

Illustration showing effect of solar farming on bat activity (Lizy Tinsley)

None of the bat species in this study were endangered or threatened. But concerns have been raised about negative environmental impacts associated with renewable energy, like birds and bats dying from impacts with wind turbines. (Whales, on the other hand, are not dying from wind turbines, despite misinformation about their impacts.) Yet sustaining human life on the planet requires energy to be sourced from somewhere — so how much do these environmental concerns stack up to other alternatives, namely fossil fuels?

Estimates vary, with one 2009 study projecting that fossil fuels are responsible for roughly 17 times more bird and bat deaths than wind farms. Another report estimated fossil fuel power stations were to blame for 34 times more avian deaths than wind facilities. Overall, the fossil fuel industry has been widely blamed for the climate crisis, with a 2017 report estimating 100 industry players were responsible for 70% of greenhouse gas emissions released since 1988.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

Changing wind speed and adding acoustic deterrents, for example, can reduce impacts with birds and bats substantially, Jones said. The bodies of birds and bats that did die on wind farms are even recycled for scientists to better understand how to design mitigation strategies.

"Now that we know bats might be an issue, we can design a solar farm that is more supportive of bats' habitat."

When it comes to solar farms, however, the consequences are much less deadly. The Applied Ecology study shows that habitat disturbance rather than mortality seems to be the bigger challenge for bats and solar farms. Importantly, there are also ways to reduce the environmental impacts of renewable energy.

Avoiding habitat disruption with solar farms could mean relocating so they are instead on farmland or other locations that don't disturb bat habitats, Jones said. Another possibility is to require solar farms to protect natural lands elsewhere and neutralize their overall impacts, said Dustin Mulvaney, Ph.D., an environmental studies professor at San José State University in California.

"The developer might be required to go out and acquire or restore some habitat elsewhere," Mulvaney told Salon in a phone interview. "It's like a biodiversity offset."

"Having these studies where they're measuring activity is important because it's basically the information we don't have," Mulvaney added.

We need your help to stay independent

Regardless of what shape mitigations take, this study puts bats on the radar for something to look out for as the country ramps up solar energy production, said Annick Anctil, Ph.D., an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Michigan State University.

"You can't solve a problem you don't know exists," Anctil told Salon in a phone interview. "Now that we know bats might be an issue, we can design a solar farm that is more supportive of bats' habitat."

Shares