Our love affair with true crime links to their duality as triggering devices and a weird type of comfort. When the crime involves murder, we double-check that our doors are locked and maybe keep a knitting needle handy. When it's a scam we assess our vulnerability and our gullibility. And when we watch stories about either we can take some dark relief in knowing that it happened to somebody else, not us. Surely we would be wiser.

"Telemarketers" pops that fantasy by diving into a type of wrongdoing that's omnipresent, nearly unavoidable and, most frustratingly, impossible to regulate – mainly because the political will simply isn't there. It's also the type of crime where the perps already have your number or that of someone you love, or will find a way to get it, preying on people's loyalty to law enforcement or desire to help the less vulnerable. Keeping our distance is nearly impossible.

"Telemarketers" scroungy realism makes it stand out in a popular mainstream genre that's been buffed to a shine.

But if this three-part docuseries sneaked into conversations recently, that's due to its atypical heroes Sam Lipman-Stern, who co-directed the project, and Patrick Pespas, an avuncular Jersey guy turned fired-up anti-corruption crusader, drawing on years of industry experience and frustration.

Before Lipman-Stern and Pespas set out to expose this endlessly sprawling grift, they worked for one of the firms that gave birth to the problem. Lipman-Stern's story starts in 2001 when he was a 14-year-old high school dropout whose parents made him get a job. Among the few places that would hire a kid with a ninth-grade education was a fly-by-night New Jersey telemarketing firm called Civic Development Group, or CDG. There he worked beside felons, moonlighting professionals and other hourly workers making cold calls to raise money for various law enforcement charities.

In reality, only about 10 percent of whatever CDG took in actually went to the charities they claimed to be helping. Most of the remaining 90 percent went into the pockets of the business owners.

Eventually the federal government shut down CDG, but other telemarketing companies quickly stepped in to replicate the blueprint CDG established, including crooked cops and, eventually, political action committees.

"Telemarketers" scroungy realism makes it stand out in a popular mainstream genre that's been buffed to a shine through the work of notable documentarians working with skilled editors and researchers. This, in contrast, is based on the work of a kid goofing with his video camera who filmed his workplace's hijinks to show what he and his co-workers were able to get away with — including shots of a heroin-hazy Pespas nodding off at his desk.

Whenever you see a Fraternal Order of Police stickers on cars or in the windows of businesses, you're likely witnessing evidence of someone who's been conned.

The joke was that all a person needed to qualify for a job at CDG was to be able to pronounce the word "benevolent." That low bar resulted in a wild workplace environment where Lipman-Stern used his video camera to film his co-workers drinking, getting high, engaging in sexual acts and destroying property. One series of clips captures a co-worker's tiny turtle crawling across his computer keyboard. This was all permissible at CDG as long as employees made their sales.

Such scenes lend the opening episode the raggedy, gonzo appeal of a low-rent imitation of MTV's early aughts hit prank show "Jackass," and take on another tone as the years roll on and Lipman-Stern and Pespas' shared interest in what CDG is really doing matures.

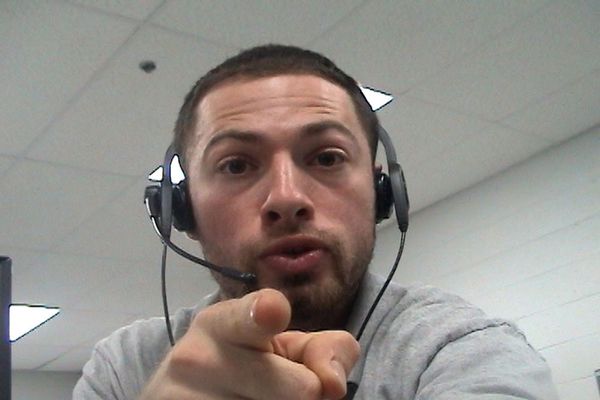

Sam Lipman-Stern in "Telemarketers" (HBO)Their moral evolution is also reflected in Lipman-Stern's steady transformation as a filmmaker over the two decades he and Pespas chase down a culprit that's constantly expanding its reach and upgrading its methods. The grimy industry that springs like weeds from CDG's grave grows into a nationwide web of fraud, whose operators claim to collect funds for cops and firefighters, but also cancer victims, disabled veterans, and other vulnerable groups, virtually unfettered by federal regulation. Some groups for whom these firms claiming to raise funds never see a dime. Others, mainly police unions, work with them, reasoning that skimming a small percentage of the take is better than getting nothing.

Sam Lipman-Stern in "Telemarketers" (HBO)Their moral evolution is also reflected in Lipman-Stern's steady transformation as a filmmaker over the two decades he and Pespas chase down a culprit that's constantly expanding its reach and upgrading its methods. The grimy industry that springs like weeds from CDG's grave grows into a nationwide web of fraud, whose operators claim to collect funds for cops and firefighters, but also cancer victims, disabled veterans, and other vulnerable groups, virtually unfettered by federal regulation. Some groups for whom these firms claiming to raise funds never see a dime. Others, mainly police unions, work with them, reasoning that skimming a small percentage of the take is better than getting nothing.

"Telemarketers"' bootstrapped feel, shaped by Lipman-Stern and his cousin and co-director Adam Bhala Lough, brings us close to a topic and a group of people we're conditioned to avoid, helping us to see how pervasive the problem has become. Whenever you see a Fraternal Order of Police stickers on cars or in the windows of businesses, you're likely witnessing evidence of someone who's been conned.

We need your help to stay independent

And as the series rolls on Lipman-Stern and Pespas reveal what kind of person may be on the other end of the phone or pulling those workers' strings – including convicted murderers and one source whose identity is hidden and sounds a lot like a low-level mob boss.

Telemarketers target those who are most likely to fork over cash out of a sense of civic loyalty or partisan allegiance, mainly the elderly.

But whether purely by accident or as a byproduct of Lipman-Stern and Pespas growing into their role, "Telemarketers" successfully shows us the structural and psychological reasons enabling this wide-reaching industry to thrive, and it in the main it all circles back to our societies tangled relationship with the cops.

As they explain, telemarketers target those who are most likely to fork over cash out of a sense of civic loyalty or partisan allegiance, mainly the elderly. More often than not they capitalize on a person's fear, whether it's the kind that makes us want to get out of speeding tickets or something more sinister, like the threat of deportation.

Among the first details the series establishes by showing a young Lipman-Stern in action is that monetary gifts are rewarded with a "thank you" decal a telemarketer encourages a donor to display in a prominent place – like say, your vehicle – as a sign or support.

But these groups also target non-English speakers, presuming that they'd rather buy off the caller who claims to be with the cops instead of attracting undesired attention.

Of course, it's less likely that an actual police officer is on the line than an ex-con who can't find more honest work. String all of this together and we have a cash cow riding an ouroboros of systemic failures, circling between the prison industrial complex and the easily exploitable through various flavors of apprehension related to the police.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

This includes their political power – near the series close, Pespas and Lipman-Stern learn the hard way how much influence police organizations wield both at the state and federal levels. Nearly everyone in a politically advantageous position to curb telemarketing scams balks at going against law enforcement organizations, aware of the sway they hold over their constituents – the same supporters whose pockets some are picking.

Pat Pespas in "Telemarketers" (HBO)It would all feel so hopeless if not for Lipman-Stern and Pespas standing shoulder to shoulder with us every step of the way, learning to swim in the sewage as they uncover, sometimes clumsily, the various sources spouting it. Pespas is especially winning as someone with a passion for doing right and ample integrity, but lacking the journalistic polish to properly chase down leads and perhaps follow up a source's answers with the obvious they may yield.

Pat Pespas in "Telemarketers" (HBO)It would all feel so hopeless if not for Lipman-Stern and Pespas standing shoulder to shoulder with us every step of the way, learning to swim in the sewage as they uncover, sometimes clumsily, the various sources spouting it. Pespas is especially winning as someone with a passion for doing right and ample integrity, but lacking the journalistic polish to properly chase down leads and perhaps follow up a source's answers with the obvious they may yield.

For some reason, he decides he needs to wear sunglasses in all of his in-person interviews as if to mimic the conversational barrier his telemarketing phone once provided. It's a personal style detail the filmmakers rarely question. Maybe they don't need to. It's enough that he's answering a call most of us are content to ignore, and intently glaring at massive wrongdoing most don't realize we may be facilitating.

The season finale of "Telemarketers" debuts Sunday, Aug. 27 at 10 p.m. on HBO. Parts 1 and 2 are streaming on Max.

Read more

about this topic

Shares