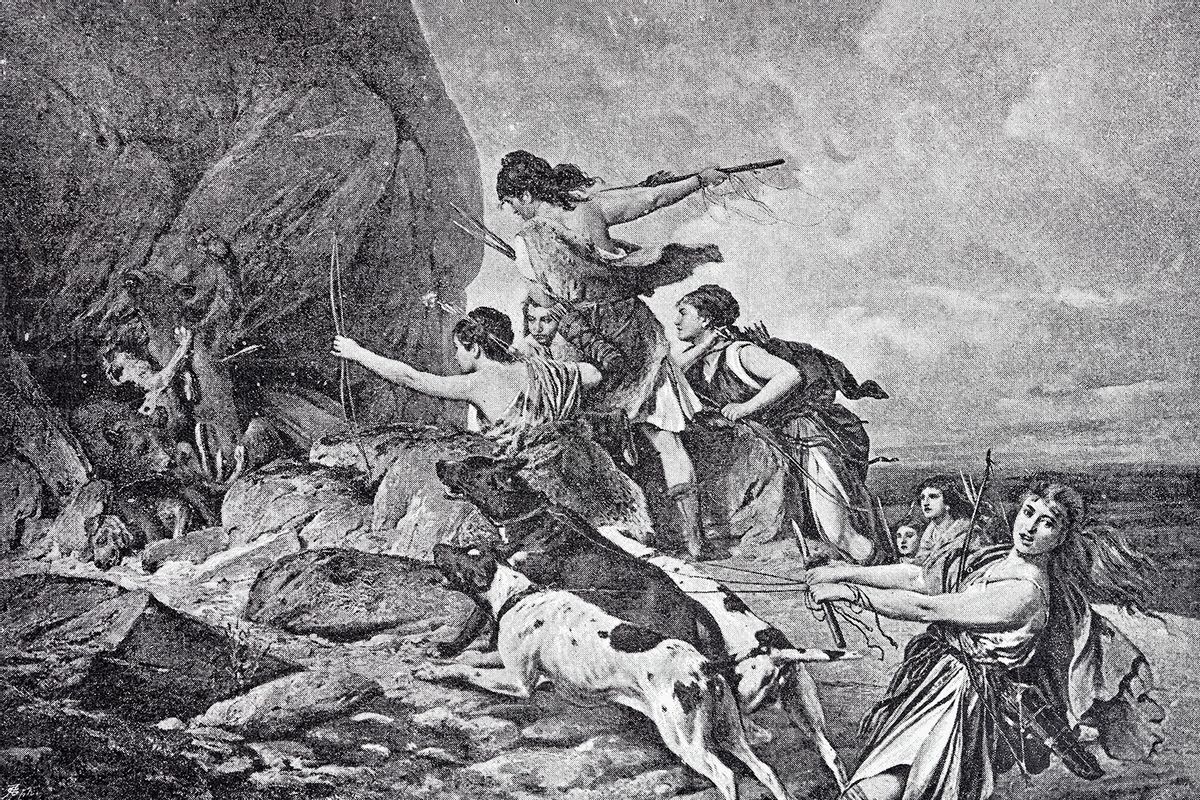

In Greek mythology, Amazonian women were fierce warriors described by Homer as antianeirai, or the "equal of men." Originally thought to be a myth, recent research confirmed these women were not merely fantasies etched into clay pots and popularized by the Wonder Woman franchise: They really existed.

Similarly, it has long been held that in prehistoric societies, men hunted while women gathered food and cared for the children. But recent research is uncovering a lost history of women hunters and questioning the evidence behind that long-held assumption. In fact, scholars have been unraveling a century-old tapestry that reinforced gender-based labor roles and discovering evidence that stitches together a different shared history since the 1970s.

Historically, there are examples of women hunting in hunter-gatherer societies, although, according to the anthropological record, it's typically only small game that they bring home while gathering. In some ethnographic studies of hunter-gatherer societies, women also participate in communal hunts, like bottlenecking a river to trap migrating animals or whacking seals with clubs when they come up for air through holes in the sea ice.

These techniques show hunting doesn't necessarily require a large body or great strength, but rather patience, stealth and knowledge, said Robert Kelly, Ph.D., a retired anthropologist formerly at the University of Wyoming who has been studying hunter-gatherer societies for decades.

"No one in at least the past 50 years has said that women are incapable of acquiring those skills, and anecdotal accounts show that some do [hunt]," Kelly told Salon in an email. "But the general pattern in the ethnographic literature is: Men hunt large game, women seek out vegetable foods."

"There have long been known ethnographic examples of women doing the kinds of tasks typically associated by us with men, but they were always sort of seen as anecdotal."

Yet many anthropologists and historians say it is time for the studies on which these conclusions are based to be re-examined. Anecdotal examples, some of which may have been overlooked, may reveal a different history when put together with some new techniques like DNA analysis that didn't exist 50 years ago, said Kathleen Sterling, Ph.D., an anthropologist at Binghamton University.

"There have long been known ethnographic examples of women doing the kinds of tasks typically associated by us with men, but they were always sort of seen as anecdotal," Sterling told Salon in a phone interview. "Part of changing that narrative involves going through all of these cases and showing that actually, it's not as anecdotal or as rare as it's been portrayed."

This summer, researchers did just that. In a study published in PLOS One, authors re-evaluated 63 hunter-gatherer societies with documented hunting records to see who was bringing home the bacon — and found women were actually hunters in nearly 80% of them. Though not everyone agrees this study debunks the idea of "man the hunter," it joins a growing body of literature that is beginning to paint a different picture of how sex affected labor roles.

In another study published last month, researchers tested how males and females used an atlatl, a common prehistoric hunting weapon. Their results suggested the weapon could have leveled the playing field between males and females when hunting.

"Archaeology, in general, has been masterful about making unjustified assumptions over the last 150 years," said study author Metin Eren, Ph.D., an anthropologist at Kent State University. "That's the strength of experimental archaeology: We can actually test a lot of these things that people have said for so long — and a lot of them turn out to be incorrect."

"Archaeology, in general, has been masterful about making unjustified assumptions over the last 150 years."

In the 1880s, anthropologists assumed a Viking warrior buried in Sweden was male because it was buried with weapons — but a DNA analysis performed in 2017 revealed it was actually female. In 2018, Randy Haas, Ph.D., an anthropologist at the University of Wyoming, also discovered that 9,000-year-old remains he discovered in the Andes in Peru that were thought to be male because they were buried with a large mammal hunting kit were also actually female. In further analysis, he found up to half of the individuals buried with these large mammal hunting tools were actually female.

"It encouraged me to reevaluate archaeological reports that had been sitting in front of us in plain sight for a long time," Haas told Salon in a phone interview.

Historically, when archaeologists found tools or weapons in a female's grave, they often assumed it was her husband's, or that it was a ceremonial symbol of her place in the clan, Sterling said.

"Typically, if you find the same thing in what is identified as a male grave, that is assumed to be his possession, something that he used," she explained.

It has also largely been assumed women would have to be responsible for breastfeeding children and might not be able to hunt large animals with an infant tethered to them. Men were also assumed to be the hunters because studies showed they had a better capacity for spatial visualization in their brains, an assumption that would later be used to explain why boys scored higher on certain math tests than girls.

Feminist theory has challenged these ideas since they were introduced. In the 1980s, evolutionary anthropologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy found primates would actually let "allomothers," or other members of the community, care for their young and even breastfeed them.

In a 1990 essay, Harvard University biologist Ruth Hubbard pushed back against the biological brain differences idea, arguing that discrepancies in knowledge were instead due to the environment and that "people from different races, classes, and sexes do not have equal access to resources and power." A new study published last week made the argument that estrogen is an important hormone for endurance and that female biology could actually improve rather than hinder women's hunting capabilities.

Female biology could actually improve rather than hinder women's hunting capabilities.

Archaeology, like any science, is partly in the eye of the beholder. The answers to questions about what prehistoric societies were like to some degree depend on who is asking them. At the dawn of archaeology in the mid-19th century, that was largely Victorian white men, said Kimberly Hamlin, Ph.D., a history professor at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio.

"We need to go back and revisit these questions and we need to acknowledge that perhaps our initial conclusions were hasty," Hamlin told Salon in a phone interview. "I don't think the evidence is going to show men never hunted and women predominantly hunted. I think there's going to be much more nuanced findings that say in some societies, women did the hunting."

In the 19th century, ethnographers observed surviving hunter-gatherer societies to look for clues that might inform their conclusions about the behaviors of these groups. Over time, examples of modern hunter-gatherer societies everywhere from tropical forests to the Arctic tundra in which men hunted and women foraged began to stack up, Kelly said.

"There's no one person who said this is the way it was," Kelly told Salon in a phone interview. "It's a piece of received wisdom that arose once we had a number of ethnographic studies conducted, which was really started in the late 19th century."

These ideas culminated in a seminal Conference on Hunting and Gathering Societies (CHAGS) called "Man the Hunter" in 1966, organized by Irven DeVore and Richard Lee to ignite discussions among the world's leading anthropologists. Two years later, they'd co-author a book by the same name, in which they wrote that hunting was "consistently a male activity" that would "become increasingly important as populations migrated out of the tropics into areas where plant foods are scarce."

In the Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology published in 2014, Lee clarified that despite the title, the book was intended to emphasize the "vital and hitherto underestimated importance of women's work in hunter-gatherer societies and in human evolution overall."

At the conference and in the book, groundbreaking evidence was indeed presented that showed women hunted small animals and were responsible for gathering up to 80% of the community's calorie intake. Meanwhile, men were "conscientious but not particularly successful hunters" taking home the remaining 20% of the community's calories.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

Some scholars like Ashley Monteigue, a cultural anthropologist, started calling these societies gatherer-hunters instead because gathering was the primary means of sustenance. But the term hunter-gatherer continued to dominate the lexicon, as did the assumption that labor roles were starkly divided by sex.

Many believe this notion has lasting impacts on how our modern society functions. After all, today, women care for children at about three times the rate of men, while handling 80% of caretaking duties for other family members. They are paid less than their male colleagues. And stereotypes still exist about women hunting in modern times.

Kelly said that when people use archaeological evidence to justify the idea that men are the "breadwinners" while women should stay home — they are wrong.

"Somehow people think that whatever hunter-gatherers do, that's basic human nature, and it dictates what it is that men and women ought to be doing today," Kelly said. "It does not."

Others see this history as something that is inherently connected to the present day. When we look to the past, it can have a normative impact that constructs what we think of as "human nature," said Nadine Michele Weidman, Ph.D., a lecturer in the history of science at Harvard University. It's not just hunting, but violence, competition and aggression that can potentially be justified by these assumptions, she told Salon in a phone interview.

We need your help to stay independent

In the 1950s, Australian-born South African paleoanthropologist Raymond Dart, who famously discovered our ancestor Australopithecus africanus, suggested that our ancestors were using bones as weapons to not only kill animals but also their own kind. Although his theory was largely rejected by the 1970s, some argue its influence can still be found in things like hyperviolent movies depicting masculine aggression in modern times.

"What we think we are at the core biologically, either in our genes or because of our primate inheritance … indicates what we think we can be or should be or can only be," Weidman said. "If we have these ideas that men are violent, men are aggressive or men are the hunters and men have always been the hunters, that gets into our psyche in a certain way and determines what we think our possibilities are."

Read more

about hunter-gatherers

Shares