Be stars are weird. They are rapidly rotating stars about 4 to 18 times larger than the sun, but a pleasing blue color surrounded by discs of gas, not unlike the rings of Saturn. They spin so fast that they approach "critical velocity" or the point where they would otherwise blast apart due to centrifugal force overpowering the star's gravity. And what they say about living fast and dying young holds true: these stars only live to be about be about 5 to 10 million years before sputtering out — a short life for a star.

These fascinating celestial bodies have captivated astronomers for generations, in no small part because of their mysterious nature. Among other things, astronomers were puzzled by how Be stars — which were first discovered by Italian astronomer Angelo Secchi in 1866 — were even formed in the first place.

Now a group of scientists have published a study in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society which offers a tantalizing clue in answer to that question: It postulates that massive Be stars – which were previously thought to exist as double stars – may in reality be triple stars.

As the authors explain in their study, Be stars "are rapidly rotating stars surrounded by a disc; however the origin of this rotation remains unclear," with the previous main hypothesis being that that two close stars transfer mass between themselves. Yet by analyzing data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite, the researchers found surprising evidence that Be stars exist in triple systems, meaning that three bodies interact with each other instead of two.

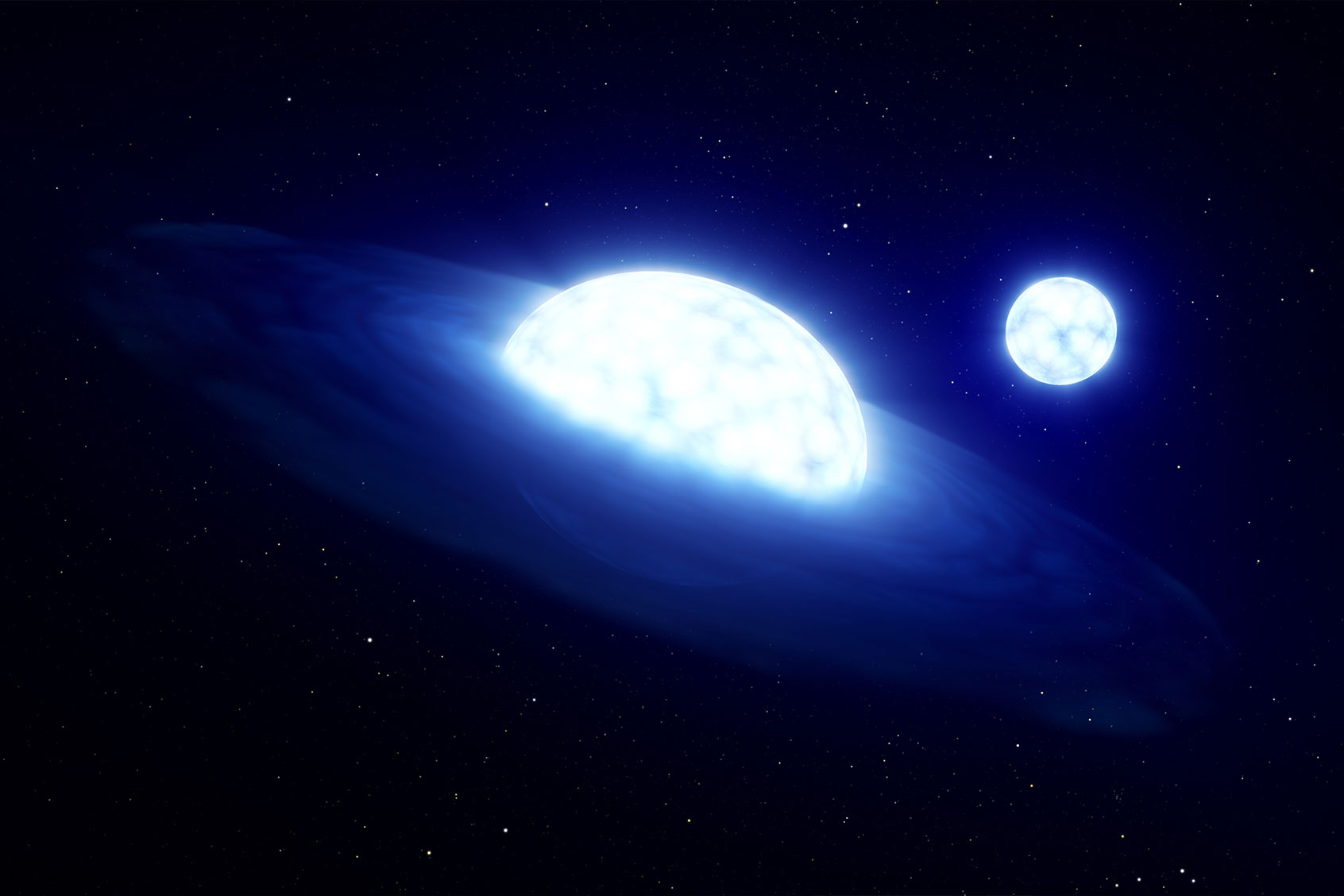

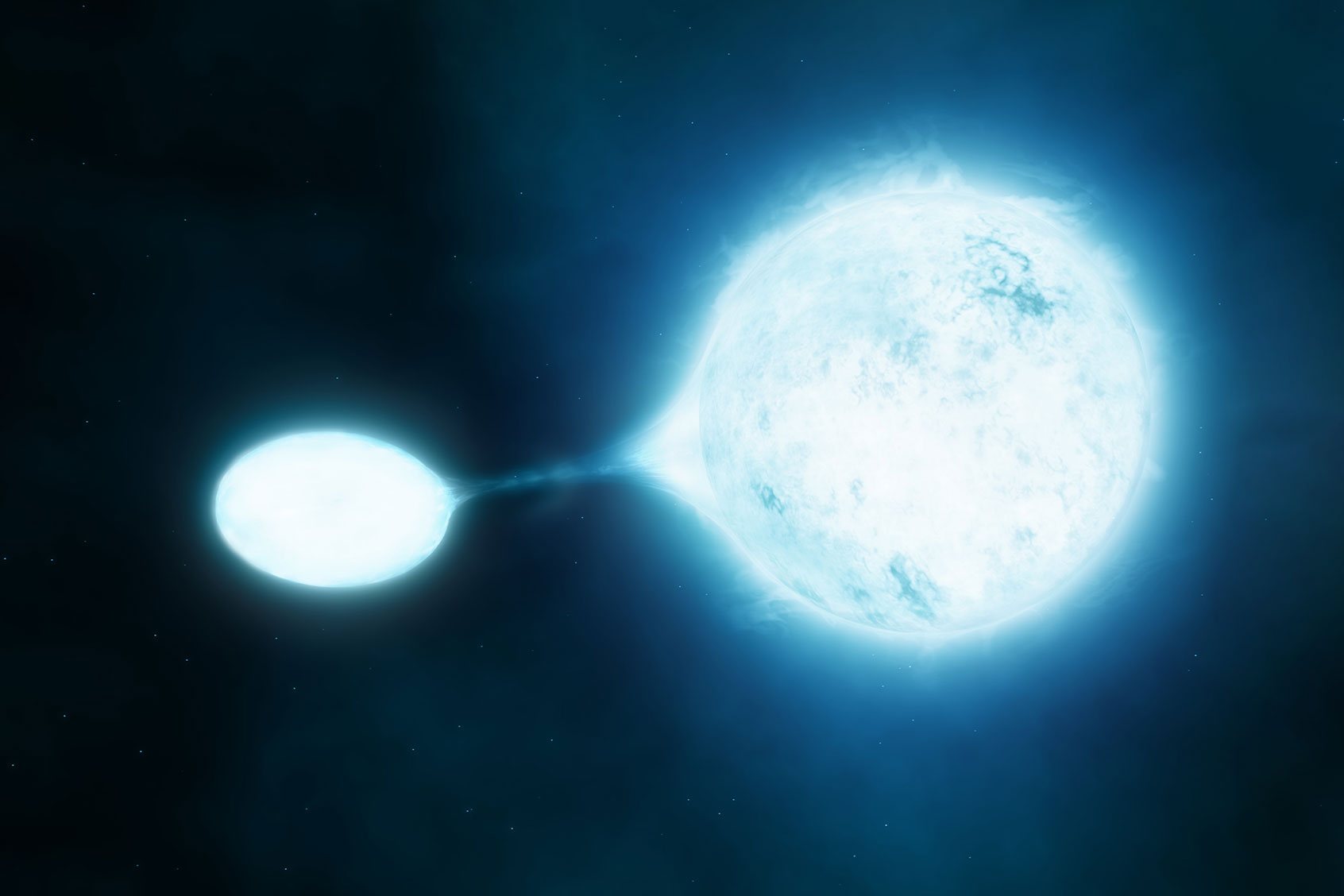

Artist’s impression of a vampire star (left) stealing material from its victim: New research using data from ESO’s Very Large Telescope has revealed that the hottest and brightest stars, which are known as O stars, are often found in close pairs. Many of such binaries will at some point transfer mass from one star to another, a kind of stellar vampirism depicted in this artist’s impression. (ESO/M. Kornmesser/S.E. de Mink)

Artist’s impression of a vampire star (left) stealing material from its victim: New research using data from ESO’s Very Large Telescope has revealed that the hottest and brightest stars, which are known as O stars, are often found in close pairs. Many of such binaries will at some point transfer mass from one star to another, a kind of stellar vampirism depicted in this artist’s impression. (ESO/M. Kornmesser/S.E. de Mink)

“We observed the way the stars move across the night sky, over longer periods like 10 years, and shorter periods of around six months," University of Leeds PhD student Jonathan Dodd, the lead author of the study, explained in a statement. "If a star moves in a straight line, we know there’s just one star, but if there is more than one, we will see a slight wobble or, in the best case, a spiral."

Dodd added, “We applied this across the two groups of stars that we are looking at – the B stars and the Be stars – and what we found, confusingly, is that at first it looks like the Be stars have a lower rate of companions than the B stars. This is interesting because we’d expect them to have a higher rate.” Dr. René D Oudmaijer, a physics professor from the University of Leeds who co-authored the paper, speculated that this may happen because some of the stars are too faint to be detected by Gaia.

"Such stars would go undetected by the measures used within this paper, as they are too close, low-mass and dim to induce a significant enough deviation of the photocentre from the centre of mass," the paper's authors explain.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

The new research may also shed light on the enigmatic phenomenon known as gravitational waves.

In addition to unlocking mysteries about the origins of Be stars, the new research may also shed light on the enigmatic phenomenon known as gravitational waves. Gravitational waves are ripples in the space-time fabric which are created in the aftermath of two black holes colliding with each other. They were first speculated to exist by acclaimed physicist Albert Einstein back in 1916, but they were not confirmed to be real for another century. Since that time, scientists have used what they have learned about gravitational waves to observe a black hole devour a neutron star, glimpse inside neutron stars and even discover the wobbliest black hole ever seen.

We need your help to stay independent

"There's a revolution going on in physics at the moment around gravitational waves," Oudmaijer explained in his statement. "We have only been observing these gravitational waves for a few years now, and these have been found to be due to merging black holes."

Oudmaijer added, “We know that these enigmatic objects – black holes and neutron stars – exist, but we don't know much about the stars that would become them. Our findings provide a clue to understanding these gravitational wave sources.”

In addition to Dodd and Oudjmaijer, the scientists behind the recent discoveries include University of Leeds PhD student Isaac Radley and a pair of former Leeds academics, Dr Abigail Frost at the European Southern Observatory in Chile and Dr Miguel Vioque of the ALMA Observatory in Chile.

Read more

about astronomy