In June, scientists presented compelling evidence that they discovered a massive "hum" of low-frequency gravitational waves rippling through the universe.

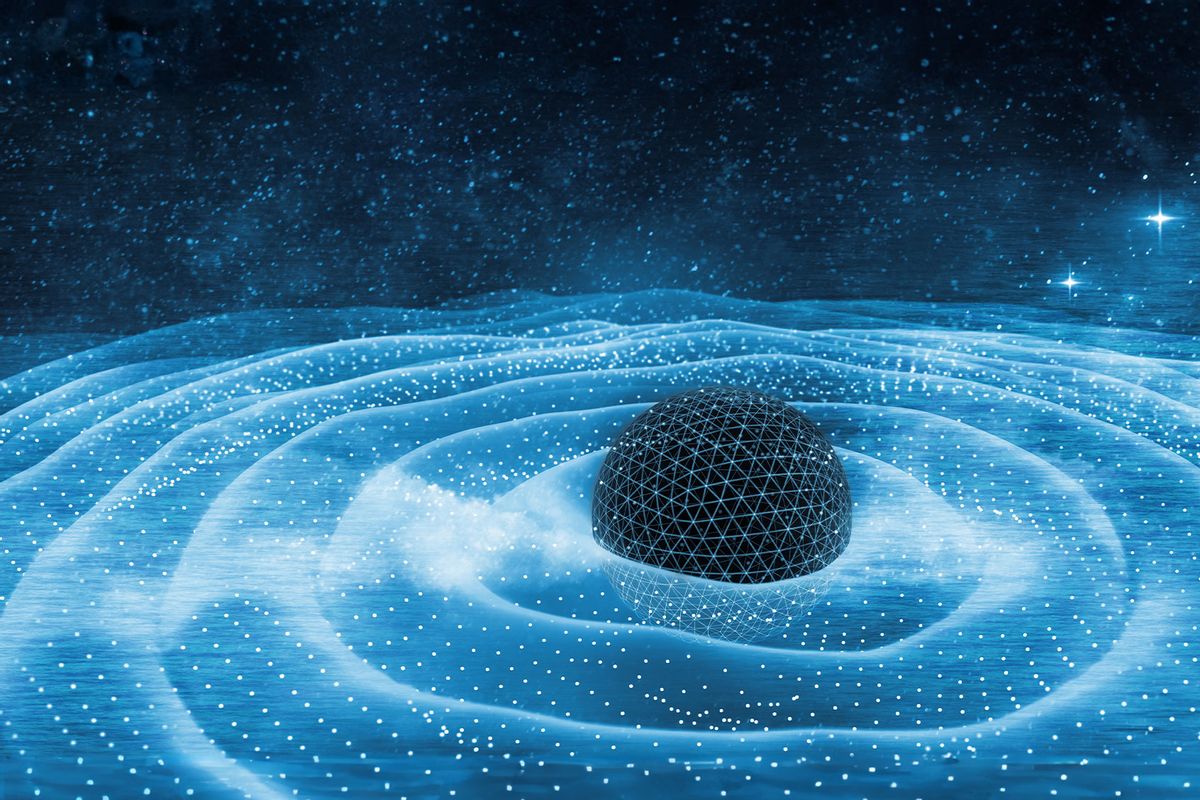

Similar to the ripple effect that occurs when a stone is thrown into the water, a similar phenomenon happens in space. Instead of creating waves that can be seen by the human eye or optical telescopes, the shockwaves that are produced from gravitational energy merging are called gravitational waves.

Physicist Albert Einstein first theorized about the existence of gravitational waves in 1916. But it wasn't until 2015, when the Laser Interferometry Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) made its first detection of gravitational waves in the universe, that scientists were able to confirm their existence. Since then, the discovery of gravitational waves have allowed scientists to peer inside neutron stars and discover the wobbliest black hole ever detected.

In June, the researchers posited that the massive hum they found was coming from the merging of two supermassive black holes, a type of explosive collision almost too big and too powerful to imagine. But as Salon reported at the time, that wasn’t the only candidate as a source.

"We found the choir, but we don't know who's singing in it — the pop stars are the supermassive black holes, they're the ones that are the most obvious candidates," NANOGrav scientist Chiara Mingarelli told Salon in June. "However, there are other potential sources of gravitational waves, like quantum fluctuations in the early universe that were driven to the size of the whole universe by inflation."

"We found the choir, but we don't know who's singing in it."

The mission to figure out the source is an international one, as scientists gather data and put it together in an attempt to construct an atlas of this background hum. In an email to Salon, Kai Schmitz, a cosmologist who is part of the international search, said scientists have been sharpening their tools and analyses further. While they don’t expect a next round of data sets to be available for another few months and / or years, "primordial gravitational waves from inflation" remains a viable option as a source, Schmitz said.

Taking a step back, Schmitz explained that the possibility that the hum is coming from the merging of two supermassive black holes got the most attention because it’s the most realistic option. We know that supermassive black holes exist, he said. Most galaxies have supermassive black holes at their center.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

“So, it's easy to imagine that when two galaxies merge, each with a supermassive black hole at its center, we ultimately end up with one big galaxy that hosts a pair of supermassive black holes at its center,” he said, adding that a possibility like primordial gravitational waves from inflation is more “speculative.”

“Whenever we speculate about gravitational waves from the Big Bang, we need to assume ‘new physics’ — [for example] new interactions, new particles, new forces that go beyond the Standard Model of particle physics,” he said. “One such scenario of ‘new physics’ is cosmic inflation, which denotes a stage of exponentially fast expansion in the early Universe.”

In other words, the theory of cosmic inflation suggests that right before the Big Bang, a faster-than-light expansion of the universe occurred in the fraction of a second. The rapid expansion occurred due to an unknown source of energy and could be the cause behind the Big Bang.

“Whenever we speculate about gravitational waves from the Big Bang, we need to assume ‘new physics.’"

“Recall that gravitational waves are exactly that: ripples in spacetime, perturbations of the fabric of space and time, that stretch and squeeze distances between objects floating through spacetime,”Schmitz said. “So, the primordial quantum mechanical vacuum fluctuations of the spacetime that are stretched to cosmological sizes during inflation continue to propagate through the Universe in the form of — drum roll — gravitational waves.”

Basically, these waves could be the sounds of the universe forever growing and reproducing. According to the cosmic inflation theory, the universe is eternal, leading to the speculative theory of pocket universes, which would mean that the universe is forever growing and reproducing. Our universe is just one pocket in this.

Another possible explanation is that the hum is also coming from cosmic strings, which are remnants from the early universe when it cooled down quickly and left cracks that are floating around in space. This could mean that we live in a cyclic ekpyrotic model, in which there is no beginning or end of the universe.

We need your help to stay independent

However, in order for theorists to find evidence for this they’re going to have to work extra hard.

“The standard picture of simple vacuum fluctuations of the spacetime metric will result in a signal that's too weak,” Schmitz said. “Instead, more complicated processes need to be at work during inflation in order to source a sufficiently strong gravitational-wave signal.”

But that doesn’t mean it’s not possible. And Schmitz has some ideas on how to proceed.

“Primordial gravitational waves from inflation may lead to an appreciable contribution to the energy density of dark radiation in the early Universe, which is a prediction that can be tested in future observations of the cosmic microwave background and measurements related to Big Bang nucleosynthesis,” he said. In other words, the more we study that massive explosions that set our universe in motion, the better we can understand how it came humming along.

Shares