I ran into an old friend a while back, someone I hadn’t spoken to in a few years, and we got on the topic of anime. Something I’m fanatical about, but something I thought he knew nothing about. “Right now I’m like 400 episodes into ‘One Piece’ and during the pandemic I binged ‘Naruto’, ‘Demon Slayer’, and a bunch of others,” he told me. He wasn’t the only one who had chatted me up about anime either.

Much the same way that comic book movies made nerding out over superheroes part of the mainstream, anime and animation are starting to have their moment. It’s been building for a few years, with more people openly talking about when they first watched the Chimera Ant arc in “Hunter X Hunter” or whole heartedly recommending “Cyberpunk: Edgerunners.” “Have you played the game? Oh, you’ll love this then,” they’ll tell you. Heck, even the New York Times is talking about Sailor Moon. The misconception that animation is only for kids, will never be breakable for some people, but more and more are tuning in and discovering animated worlds of magic that they have been neglecting all this time. The tide is turning, and I’m here for it.

This year had numerous successes. “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” proved that movies based on video games could do big numbers at the box office, something that will undoubtedly lead to more video games being adapted. “Nimona” finally had its day in the sun after Blue Sky, the original studio working on the film, was bought and then quickly shuttered by Disney in 2021. It was touch and go whether the film would ever be made, but the queer story about a shapeshifter finally made it to Netflix. The nerdy cult hit “Scott Pilgrim vs. The World” came back in animated form in 2023, with “Scott Pilgrim Takes Off” bringing the entire cast from the film back for a new take on its story.

(It should also be worth mentioning that Disney did not have a great year, with excitement dying off fairly quickly for both “Elemental” and "Wish”. Making waves online for the wrong reasons. When the titles in this list are elevating animation, delivering stories that resonate, and experimenting with form and technique, the big D is simply getting left behind.)

Anime had a banner year as well, doing a little bit of something for everyone. “The Dangers in my Heart” gave us an emo loner falling for the most popular girl in his class, their completely opposite social standing in fact making for a lot of common ground. Meanwhile, “Insomniacs After School” delivered a romance that can only be described as all about the vibes. Featuring a pair of high schoolers who bond over their shared insomnia, staying up late, exploring their small town by moonlight and the excitement and comfort of finding that one person they can truly open up to. “Oshi no Ko” came out of the gate storming with a supersized first episode that played itself off as a critique of the pressures of Japan’s pop idol industry before ratcheting the stakes up to 11 as the credits rolled. The premiere episode shocked viewers, creating unreal buzz online, as those who had seen it were shook, and those that hadn’t yet seen it had to put up blinders to avoid spoilers. Massive shonen franchises continued to dominate fandom, with “Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba” continuing to print money with its latest season, while “My Hero Academia,” “Jujutsu Kaisen” and old stalwart “One Piece” all delivered high quality action and impressive animation.

But when settling on what were the most significant moments this year, I tried to determine which ones made the biggest waves in the cultural zeitgeist. Whether that be through exceptional animation and storytelling, thematically striking a chord with viewers or sheer amounts of hype making a show unavoidable, the works on this list make up some of the most talked about anime and animation of the year.

Attack on Titan: The Final Chapters: Part 2 (Hajime Isayama/Kodansha)

Attack on Titan: The Final Chapters: Part 2 (Hajime Isayama/Kodansha)It’s over! It’s finally over!

There are very few anime that can generate the level of buzz that “Attack on Titan” has over its intermittent 10 years on the air. It rocked the anime world in 2013 with one of the most impactful first episodes ever. The internet and social media still weren’t quite as integrated into everyday life then, but folks found ways to talk about “Attack on Titan.” Blogs, forums, fansub communities – it was unavoidable. Everyone had seen it, everyone was hooked.

This year we reached the end of author Hajime Isayama’s polarizing story, the final part of the final season, and the excitement from fans was so great, it shut down Crunchyroll’s servers temporarily. Whether this surge of viewers crashing the site was out of genuine investment in the stor, or folks tuning in to witness a trainwreck in all its glory is unknown. It’s sort of a “Game of Thrones” Season 8 situation with “Attack on Titan,” but regardless, it was one of the biggest anime events of 2023.

Released in the form of two supersized episodes, clocking in at 145 minutes between the two of them, “Attack on Titan’s” final season attempts to wrap up a story that has gone far beyond the walls of the medieval fortified town besieged by giant beasts we saw in Season 1. Eren Yeager’s savior complex to free his people from oppression and idealism to rid the world of violence completely by turning the world against him reaches its climax here. And after skirting past some uncomfortable symbolism that drew comparisons to Jewish persecution during WWII back in Season 4, “Attack on Titan’s” complicated, at times not always coherent, look at systems of oppression, fascism and empire somehow stuck its landing.

Right from Episode 1, “Attack on Titan” has delivered top tier animation, truly something that reaches the level of spectacle. While Seasons 1 through 3 were handled by WIT Studio (who in my opinion did better work), this final season was handled by Studio MAPPA, a titan in the industry itself. There are extended sequences of intense action throughout these final two movie-length episodes that are frenetic, over-the-top and breathtaking. Director Yuichiro Hayashi balances these action heavy scenes with needed exposition to feed the viewer with the show’s final philosophical and thematic musings. Hiroshi Seko, who has written scripts for the series since its earliest episodes in 2013, condenses a lot of Isayama’s work into these supersized episodes, tying together the many themes of the show. Completing the package, Kohta Yamamoto’s soundtrack drives the action and hits the emotional beats when it needs to.

“Attack on Titan” made an impact in 2023 as the most anticipated anime finale of the year. Fans knew this day would come, though few thought it would take 10 years to get here. No other show crashed streaming service servers like “Attack on Titan” did (although Netflix had a hiccup with its second live outing). It was appointment viewing. This is a show that pulled in fans from outside the usual anime viewer and delivered a product that was full of bombast, melodrama, while not shying away from asking tough questions of its audience. Whether those questions were always clear is up for debate and the themes were muddled at times, one thing “Attack on Titan” never was, was boring.

Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End (Kanehito Yamada, Tsukasa Abe/Shogakukan)

Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End (Kanehito Yamada, Tsukasa Abe/Shogakukan)At an initial glance, Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End looks like a lot of anime out there. Vague European medieval fantasy setting, stoic elf girl, characters with silly hair color. Have I seen this anime before? Trust me, you have not.

“Frieren” begins at the end. Not in an in media res way though with a cheeky “yeah, that’s me, now let me tell you how I got here . . . ” but at the actual end of our heroes’ journey to slay the Demon King. For Frieren, the titular character, this journey passed by in the blink of an eye. Her lifespan being many hundreds and perhaps thousands of years longer than her human companions, means a mere 10-year adventure wasn’t much at all. Her fellow heroes see it differently. It meant everything to them. “Frieren" plays with memory and our relationship to time. How do we define the time we have on this Earth?

The story leaps ahead 50 years, with Frieren returning to the capital of the kingdom she saved all those years ago. She reunites with the heroes she journeyed with only briefly, before the hero Himmel passes away. It is here that Frieren realizes she never knew anything about Himmel and she is struck with an incredible sense of regret for not cherishing those 10 years of adventuring more. Himmel’s death affects Frieren greatly, and after meeting with Heiter, another of her fellow heroes, he gives her a new purpose, to train a young mage and set off on a new adventure.

“Frieren" is being handled by Madhouse, one of anime’s premier studios. It is known for producing the works of Satoshi Kon, the famed director of critically acclaimed, cult classic films "Perfect Blue," "Millennium Actress," "Tokyo Godfathers" and "Paprika." Madhouse has also given us the terrific "Hunter X Hunter" adaptation, Mitsuo Ito’s "Dennou Coil," "Death Note," "Sonny Boy" and a host of other beloved series. This is director Keiichiro Saito’s newest project after 2022’s surprise hit "Bocchi the Rock!," and in his hands the source manga by Tsukasa Abe and Kanehito Yamada comes to life on the screen. Frieren’s journey through pastoral countrysides and across towering mountain ranges looks amazing. While the series does feature fights with antagonistic demons, where exciting flourishes in the animation wow the viewer, the bread and butter is the detail in the quotidian moments of a slow-paced journey through quaint towns and in memories Frieren recalls as she revisits places from her past.

“Frieren” excels when it is interrogating how we make sense of time, how we form memories, and, much like Miyazaki’s “The Boy and the Heron,” how do we live? We begin to see that Frieren has in fact made some long-lasting memories over the years; she just couldn’t see it at the time. Each flashback we get reveals more of Frieren’s true self to us, providing us with wonderfully emotional story beats that show us Frieren’s growth as a person, without cheapening a moment by dipping into melodrama. The burden of regret, of guilt, lessens as Frieren realizes she did care about her companions and she holds them tightly in her memory. She uses those memories to enjoy the time she has with the young mage Fern, and the newly minted hero Stark. When you add an exceptional score by Evan Call ("Violet Evergarden"), it completes the package. An ambling tale of adventure that takes its time to reach its destination – or maybe what matters most is the journey.

Maya Erskine as Mizu in Blue Eye Samurai. (Courtesy of Netflix)

Maya Erskine as Mizu in Blue Eye Samurai. (Courtesy of Netflix)What if “Kill Bill,” but anime? A tale of revenge in 17th century Japan delivers all the spectacle, bombast and edginess you would expect from a Tarantino film, in beautifully animated form.

The story of the titular blue eye samurai is that of Mizu, a mixed-race woman whose piercing blue eyes reveal to all her mixed heritage, which she hides behind orange-tinted sunglasses to not draw attention. She has been labeled a “white devil” and now seeks revenge on her father for cursing her with these eyes. Her father is one of four white men who came to Japan as the country began to open its ports to foreigners and are now believed to be hiding out as the nation begins to close its borders once again. Mizu is a skilled swordswoman, and the search for her father is a bloody one, confronted by samurai looking for a fight or by roving armies serving local lords. Mizu’s story intertwines with that of Princess Akemi, the daughter of a lord, who is reluctant to wed the man her father has chosen for her. In this first season (the show was recently announced as being picked up for a second), Mizu’s focus is on the thoroughly contemptuous Abijah Fowler, an Irishman who seethes and sneers with every word he speaks. Mizu searches for information on the whereabouts of Fowler, who is mostly confined to his castle, unable to move freely about the country due to the whole closed borders situation. He awaits Mizu’s arrival like the final boss of a video game.

“Blue Eye Samurai” impresses with its blending of 2D and 3D animation. The painterly backgrounds are gorgeous, and the camera work employed is strikingly cinematic in feel. Anime tends to have its own visual language, but “Blue Eye Samurai” brings a bit of a Hollywood lens to its anime-like world. The camera is very active, with dolly-style shots, swoops and wide panning shots while the framing and composition have all the hallmarks of filmic technique — as opposed to anime-ic, though that’s not to say that the two are mutually exclusive. "Blue Eye Samurai" leans more towards its Tarantino influence than the techniques employed by anime directors like Shuhei Yabuta. It creates a different feel, but is something that it pulls off well. Something else this series nails is its fight sequences. Any revenge tale needs to make the scenes where the protagonist exacts that revenge look appealing. “Blue Eye Samurai’s” fights are crisp, engaging, bloody and just exaggerated and extreme enough to rev up the audience without feeling gratuitous.

“Blue Eye Samurai” is a big swing for Netflix this year in their attempt to bring mature animation to its audience, having already found some level of success with its “Castlevania” series. Netflix continues to show interest in building properties with that anime aesthetic. Showing off a successful series like this could mean more mature animation in the future. There are some issues with dialogue that borders on so edgy it falls into cringe, as well as some not particularly fitting dialogue for the time period in which this story is set. The word "orgasm" is used, when that would have been just breaking over in France at the time. So unless Princess Akemi had the trendiest French magazines, it just doesn’t make sense for her to use it. Yes, I know it’s super pedantic, but when they get Mizu’s animation right for sitting in the formal kneeling, or seiza, position, to toss in idioms that didn’t exist at the time or have characters slide in a "f**k" for emphasis, it pulls you out of what is otherwise a beautifully realized 17th century Japan. “Blue Eye Samurai” is worth your time for its compelling main character, excellent background art and some truly kick-ass fight scenes.

Suzume (Toho/Crunchyroll)

Suzume (Toho/Crunchyroll)A love story as old as time. You know the one. About the girl and her . . . chair?

March 11, 2011 is a date seared into the Japanese consciousness. It was the day when a powerful earthquake created a tsunami that washed away entire towns along Japan’s northeast coast and irreparably damaged the Fukushima nuclear power plant. “Suzume” director Makoto Shinkai has spent the better part of three films (2016’s “Your Name,” 2019’s “Weathering With You,” and now “Suzume”) trying to make sense of the disaster’s impact on Japan. Whether metaphorically or, in “Suzume,” more directly, it has been a theme that has woven itself into his works.

Suzume Iwato is a typical high school girl who lives in a small, coastal town on the island of Kyushu with her aunt Tamaki. A chance encounter with Souta Munakata, a mysterious (and very handsome) stranger sends Suzume on a road trip across Japan chasing a cat and closing magical doors. There is a world on the other side of these magic doors, and Suzume seems to have a connection to this other world. The first door is found at an abandoned hot spring resort near her town, and after Suzume sees a large dark cloud billowing from the area near the resort, she rushes to the scene and finds Souta trying to close the now open door. They manage to do so, but this sets off a chain reaction of doors across the country opening. The worm, a cloudy entity that emerges from each door, is the cause of earthquakes in Japan, and if it escapes the other world, it will unleash a devastating earthquake wherever it appears. While Suzume tends to the injuries Souta sustained during the encounter with the worm at the hot spring resort, a talking white cat appears in the window of Suzume’s house. The cat is the keystone that will lead Suzume to the other open doors, and isn’t a fan of Souta, so it turns him into a sentient chair. Suzume, Chair Souta and the little cat Daijin make their way across Japan to stop the worm from getting loose, while Suzume reckons with her past and maybe, just maybe, falls in love with a piece of furniture.

The art in “Suzume” is, as is to be expected with a Shinkai picture, nothing short of stunning. Since "5cm Per Second" all the way back in 2007, Makoto Shinkai and his team have delivered the very best in background art, scenery, and landscapes. Producing shots so photorealistic that they border on the hyperreal. It is the perfection of representing the everyday mundane spaces of Japan in the most magical way that blends the fictional with the real. The scouting team for a Shinkai film will photograph real places, and those become the basis for these representations that are the most gorgeous fictionalization of that place possible. It is easy to imagine that what ends up on the screen is the reality. This has always been Shinkai’s greatest strength. Moments when the worm appears are also striking and limited edition chair version Souta is wonderfully animated. Popular Japanese band Radwimps continues their collaboration with Shinkai (having worked on "Your Name" and “Weathering With You” as well), providing the score for the film alongside composer Kazuma Jinnouchi.

Makoto Shinkai is a bonafide hitmaker and one of the most respected directors in anime. When one of his films comes out, it is an event. “Suzume” looks fantastic. Shinkai and his talented team of animators at CoMix Wave Films are unmatched at making a hyperreal Japan seem so inviting. “Suzume” is an interesting film in that it seems to be reaching for greater thematic depth, but doesn’t quite coalesce around any philosophical themes to ground the film. Nevertheless, the dual earthquake and meltdown aftermaths, however, may resonate with Americans, who had endured a record-breaking number of natural disasters this year. As climate change continues to wreak havoc, this trend sadly doesn't seem to be going away.

Shinkai has said he wanted to "mourn deserted place"’ which is why the doors in the film appear at an old school, an abandoned theme park and in the Tohoku region of Japan still recovering from the tsunami. Yet, he doesn’t seem to be saying anything about these places. Is it capitalism’s fault? Is it a loss of connection to community? Is it nature taking revenge on human kind? It’s not clear. What is clear is that Shinkai is much better at writing love stories. He wrote one of the most genuinely bittersweet romances ever in the first part of “5cm Per Second” in 2007, and while he has trended towards happy endings lately, he writes love well. He knows how to hit the right emotional notes between Suzume and chair Souta, and their relationship carries the film well. And sometimes we need that in our films.

Heavenly Delusion (Masakazu Ishiguro/Kodansha)

Heavenly Delusion (Masakazu Ishiguro/Kodansha)When the world ends, why not go on an adventure?

Post-apocalyptic fiction is one of those done to death genres in the mainstream. While it is a place where societal critique can be magnified, and there are ways in which the post-apocalypse can be used to radically reimagine society, more often than not, it can feel almost rote and by the numbers. So how do you take a post-apocalypse story and make it memorable? Well, one way to do it is to animate the heck out of it. Make a show so gorgeous, it can’t be denied.

"Heavenly Delusion" is a story that splits its time between two drastically different places in its post-apocalyptic world. The more mysterious narrative is the one set in a clinical, futuristic orphanage. The kind of sci-fi utopian location that, from the get-go, you can tell that something is definitely off about the place. The kids seem healthy, they’re being educated, they have ample free time to play and pursue hobbies. But as the kids begin to get curious about “outside” and wonder if there is a world beyond the walls of the orphanage, they begin to uncover secrets about the only home they’ve ever known. On the flip side, a more straightforward search for a place called Heaven somewhere out there in the crumbling remnants of Japan is what drives Maru and Kiruko, a teenage duo who get along almost like they’re in a buddy cop flick. This world is extremely dangerous, but for every tense encounter with a monster or hostile humans the pair crack jokes that cut the tension. They’re just kids after all, they’re goofy, awkward, and hormonal at times. The beautiful landscapes the duo travels through hide many unknowns and the journey stirs up lingering trauma that reveals itself slowly to the viewer.

“Heavenly Delusion” is animated by Production I.G., another of Japan’s best studios, with a team of experienced animators who have experience working with each other. That ability to play off each other's strengths has an obvious, and extremely positive, impact on how "Heavenly Delusion" looks and feels. While many anime start with their strongest material to pull a viewer in and then let the quality slip a little in later episodes, “Heavenly Delusion” looks absolutely gorgeous from start to finish. There are so many little details that give the production so much life. Simple things like each character having a unique walk, or visibly different levels of physical ability, each character’s movements add to their personality. While the background art is stunning, the color design is also worth noting. Color sets the mood in a show like this, coloring the world to give it an authentic, lived-in feel, while also making bold choices to heighten emotional response. Action sequences crackle with intensity whether it’s a fist fight with some local toughs, or a harrowing encounter with one of the many dangerous monstrosities that lurk in this beautiful post-apocalyptic nightmare.

“Heavenly Delusion” is arguably the best looking anime of 2023. The rich world that manga author Masakazu Ishiguro has created is breathtaking to behold in animated form. It is a production that has been in the works for some time, and that long production time has meant that a great deal of care has been put into this adaptation. The mysteries on both sides of the narrative coin are intriguing, keeping viewers invested as we peel the layers away and get to deeper truths about this post-apocalyptic world.

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem (Paramount Pictures)

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem (Paramount Pictures)As a millennial, I have seen more than enough of the treasured properties from my childhood mined from my memories and reassembled into some kind of facsimile of the thing I remember. I’m supposed to watch these reimagingings, reboots and remakes with the highest prescription rose-tinted glasses available and eat up the nostalgia slop like a good little consumer piggy. So you’ll have to forgive me for thinking that the latest TMNT film was another attempt to cash in on my love for the '80s cartoon (have you ever heard the Japanese dub’s ending theme? Bass line absolutely slaps). Watching "Mutant Mayhem," I was ecstatic to see that this film was not solely aimed at me. I never felt like my memories were being exploited, and the film stands fully on its own without giving in to gratuitous levels of *wink wink* “did you get the reference we did there?” (though there are still enough of those if you’re looking for them). If I were a kid today, this movie would be totally radical.

With that said, “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem” is a reboot of the Turtles franchise. It starts with an origin story of how the turtles came to be, and the plot is a tried and true take on the outsiders who want to be accepted, as the turtles – Leo, Raph, Mike and Don – skirt around the fringes of society and want, more than anything, to go to school and be normal kids. They know enough about the human world to concoct some plans they think might get people on their side. Top of that list is to become heroes, and once the humans realize how cool they are, they’ll immediately be accepted in the school hallways where they can nerd out about “Attack on Titan” with the human teens. Or at least, they think it will be that simple. Unsurprisingly, their plans do not go off without a hitch, and they find themselves caught up with a gang of other mutants (all the baddies we millennials remember from the comics & the original cartoon) to destroy New York. The story plays it pretty safe, but again, this is absolutely fine. This movie is meant to be accessible enough for kids.

The art style employed in “TMNT: Mutant Mayhem” is an absolute standout. Inspired by scribbled notebook drawings, the film has a frenetic energy to it that is conveyed in the animation. Effect lines, exaggerated reactions and roughly sketched bits and pieces give it the energy of a 2D comic book panel exploding out of the page and onto the screen. The movements are fluid, but retain that comic book appeal as the characters strike and hold poses as they would if they were in the pages of a comic. The art in the film also makes a character out of New York City, from Times Square and the Brooklyn Bridge, to the bodegas and brownstone apartments, the city feels alive. French studio Mikros Animation and VFX studio Cinesite deserve praise for bringing director Jeff Rowe’s vision to life.

“TMNT: Mutant Mayhem” is a reboot that is truly rebooting for a new generation of kids who might not be as familiar with the Ninja Turtles, and not for us goober millennials chomping on 'member berries. Too often an old franchise makes a return out of nowhere, old actors are dragged out of their nursing homes to do a little nostalgic song and dance for us, and we’re supposed to remember the good times. It’s a transparently cynical cash grab. This film feels fresh, even if, to an older audience who is familiar with the Turtles, it might seem like a retread. Once again, it’s not just for us. The voice actors playing the Turtles – Micah Abbey (Donatello), Shamon Brown Jr. (Michelangelo), Nicolas Cantu (Leonardo) and Brady Noon (Raphael) – feel like real kids, because they ARE real kids. In interviews, it has been shared that the actors recorded lines as a group, with the kids improvising and riffing on each other. This makes perfect sense because the dialogue actually sounds like teens do. What all this does is creates an authentic film, with voice performances that hit and animation that is playful, fun and unique.

Pluto (Netflix)

Pluto (Netflix)How can you take one of the most iconic manga and anime franchises of all time (“Astro Boy”), somehow turn it into a noir thriller, and end up creating a series that honors the legacy of “Astro Boy’s” creator, Osamu Tezuka, while also being something extraordinary and entirely its own thing? “Pluto” is an adaptation of the manga by Naoki Urusawa, itself a reimagining of the Greatest Robot on Earth arc from Tezuka’s “Astro Boy” manga. Urusawa is also the author of “Monster,” one of the underappreciated (by western audiences at least) gems of both manga and anime, having received multiple awards in Japan for the manga, and a full anime adaptation in 2004. For years veteran anime producer and studio head Masao Murayama has wanted to see “Pluto” in anime form. His studio M2 is behind production here for Netflix and in interviews claims that his team have suffered in the making of “Pluto,” putting in incredible effort to do justice to Urusawa’s work.

While “Pluto” is a densely layered work about artificial intelligence, personhood, humanity and geopolitics, its plot is centered around the robot Gesicht, a detective for Europol tasked with solving a series of grisly murders. Both robots and robot-sympathizing humans are targeted, and Gesicht has to figure out what connects these crimes. As the plot expands, it appears that someone, or something, is targeting the strongest robots in the world, of which Gesicht is one. The series becomes a race against time to find out what this evil force is, and prevent it from reaching these fascinating robots, many of whom were once instruments of war, now serving the public and beloved by most everyone.

“Pluto” has an almost retro look to it, which makes it immediately stand out against the copy/paste design trends of its weaker contemporaries. A throwback to the highly detailed, grittier designs of '90s anime, “Pluto’s” animators sell the series aesthetic. This is probably a result of putting a legendary animator in the director’s chair for the project. Toshio Kawaguchi has been a key animator on several Studio Ghibli films, the 1988 masterpiece “Akira” and the 1985 cult classic “Angel’s Egg” – and while this is his first time working as a director, it appears he is up for the challenge. With a team made up of veterans from Madhouse, the level of polish puts “Pluto” into the highest tier of anime production. The show is anchored by a stellar voice performance from Shinshu Fuji as Gesicht, slowly breaking his robotic facade as the case ratchets up, allowing human emotions to start manifesting in his psyche. Once a cool customer, Gesicht reels when remembering past trauma and the injustices inflicted upon robotkind in a society still not all the way accepting of robot personhood.

“Pluto” has been years in the making. A universally acclaimed manga based on a story told by the father of anime, and given an adaptation worthy of the source material. “Pluto” is also a big deal because it tackles big themes that are relevant today. While the manga was written in the early 2000s, and the geopolitics being critiqued were those of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, when a character from a fictionalized Persia monologues about how his country was "bombed to ashes" because the imperial powers needed a "country of have-nots" to demonize, one can’t help but see how these themes and ideas are still front and center today. This is a serious anime that asks serious questions.

Scavengers Reign (HBO Max)

Scavengers Reign (HBO Max)Sometimes you put a new show on and you can immediately tell “oh, this is special.” From the opening frame, “Scavengers Reign” showcases an aesthetic that feels like a graphic novel brought to life. If early anime was seen as a way to bring manga off the page — it wasn’t called manga eiga or "moving picture manga" for nothing — ”Scavengers Reign” is nothing short of graphic novel eiga. It is a graphic novel moving on the screen.

“Scavengers Reign” follows the parallel stories of the displaced crew of the interstellar cargo ship Demeter 227 as they attempt to make their way back to their ship, which has crash-landed on a strange alien planet. While at first we know nothing about the crew, flashbacks are employed deftly to build character and establish connections between the crew members and flesh out their personal histories. The alien planet is filled with flora and fauna that are as deadly as they are beautiful. While some characters have either learned about, or had previously studied, the lifeforms of this hostile planet, more often than not, an encounter with a creature is a harrowing ordeal. This world is rich with its own ecology. When our characters stop to observe, we see the planet in its natural state. Plants blossom, little critters nibble at the flowers, bigger critters take chunks out of the little critters. Circle of life. The pacing between the stories is perfect. Told in little snippets that feel like chapters in a graphic novel, "Scavengers Reign" keeps the narrative plates spinning, never letting one slip.

“Scavengers Reign” looks fantastic. Plain and simple. As I mentioned earlier on, this show feels like a graphic novel in motion. It is an aesthetic that stays consistent throughout. The art style immediately draws those comparisons, but it’s more than that. I couldn’t get away from thinking that each cut in a scene was my eye moving to a different panel on the page of a graphic novel. The storyboarding is so exceptional, creating that paneled aesthetic to each scene, and the framing and composition of each shot is so crucial, as there is intentionally little camera movement. Pans are used sparingly, there are no fades between scenes, in fact, when we do move to a different storyline, the only scene transition we get is a sharp cut to black and then another equally sharp cut into the next scene. Turning the page, starting the next chapter.

“Scavengers Reign” flawlessly integrates another medium entirely into its aesthetic. The series is is deceptively simple looking, but the discipline of the techniques employed to create this simple look are masterful. This is a mature series, but not in a gratuitous or edgy sense. It is refined, doesn’t hold the viewer’s hand, and doesn’t use cheap trickery or melodrama to create emotional resonance. The graphic novel look and feel is something I haven’t seen pulled off so effectively before. Now I just want Tillie Walden’s “On a Sunbeam” to get the same treatment.

Mobile Suit Gundam: Witch From Mercury (SOTSU/Sunrise/MBS)

Mobile Suit Gundam: Witch From Mercury (SOTSU/Sunrise/MBS)For over 40 years, the Gundam franchise has told stories about boys who pilot giant robots. Series creator Yoshiyuki Tomino has been spinning yarns about the damage done by war, and the idealistic youth who take up the mantle for a better tomorrow. Yet, for all its history, and for the many series that make up the iconic franchise, there hasn’t ever been a female lead protagonist in a Gundam series. Until this year’s “Mobile Suit Gundam: Witch From Mercury.” That the show is also the franchise’s first front-and-center queer romance makes it an even more remarkable achievement.

The show follows Suletta Mercury, an awkward Mercurian girl, attending the prestigious Asticassia Academy, where the best and brightest pilots and robot mechanics gather (along with a healthy dose of nepo babies) to learn the ins and outs of mobile suit manufacturing and the business behind them. Because Suletta’s home planet of Mercury is considered to be the sticks, the blue blood elites that make up most of the student body immediately turn their noses up at Suletta. As an outcast, Suletta begins to doubt herself and it isn’t until she runs into Miorine Rembran, the daughter of business magnate Deling Rembran, that she finds an ally. Despite Miorine’s frosty personality, she can’t shake that there is something special about Suletta, and she warms up to the bumbling, stuttering Mercurian. The two team up, along with fellow outcast students from Earth House — Earthians being seen as less than the elite Spacians who make up the nepo baby contingent — to dismantle the corrupt power structures of the academy, and challenge the authority of the adults who are using their children like pawns.

The Gundam franchise has long been made by a passionate group of artists, animators, writers and directors. The studio behind it, Sunrise, doesn’t put its name towards too many other projects. Gundam is their baby. Each series in the franchise has its own look and feel. In “Witch From Mercury,” that look and feel starts with the character design. With characters created by the artist Mogumo, “Witch From Mercury” makes it easy to get invested in its story as each character’s design is memorable and expertly drawn. There isn’t a single character I don’t like the look of in this show. Another staple of any Gundam series is the design of the giant robots. The mobile suits in “Witch From Mercury” are interesting, and the Gundam that Suletta pilots, Aerial is a fantastic design. There is a good reason why the Aerial model kit had the highest initial sales in the history of the franchise. These giant robots also engage in some wonderfully animated battles. Though “Witch From Mercury” isn’t as battle-heavy as some past entries in the franchise, when a fight breaks out, it usually looks pretty darn good. Tying all this together is an exceptional soundtrack from Takashi Ohmama, the blend of stirring orchestrals and moody synth-focused pieces highlight and accentuate the story perfectly.

“Witch From Mercury” proudly plants its queer flag in the very first episode, with Suletta winning a mobile suit duel, the result of which earns her the title of Holder. In the world of Asticassia, the Holder is the person who will become Miorine’s fiancée. Did I mention that Miorine’s dad owns the school? And his daughter is essentially the prize to be given away as a result of these duels that take place at the school. And the whole idea is to give the Holder title to another nepo baby to strengthen Deling Rembran’s Benerit Group (a massive multiplanetary conglomerate). The adults in the room are repeatedly caught with their pants down. Making the kinds of business decisions that inflict suffering on marginalized groups, these CEOs and self-proclaimed great minds are a detriment to humanity, and are shown to be foolish buffoons often. Series creator Tomino has long said that adults aren’t to be trusted, and in “Witch From Mercury,” the kids at Asticassia put these adults, who hold so much power, in their place.

But what is “Witch From Mercury’s” most significant impact in 2023? Not only has the show been a huge hit, bringing in new fans to the world of Gundam, it wastes no time taking shots at Japan’s conservative, and frankly embarrassing, position on same-sex marriage. This year, a number of smaller Japanese courts ruled that the country’s ban on same-sex marriage was unconstitutional, but despite this, the Diet, Japan’s national legislature, has bailed on making a ruling to overturn the ban. Under this political climate, “Witch From Mercury” centering a queer romance is a big deal. Advocacy groups are fighting for equality, and here is a show, from a major Japanese anime studio, saying that this is love and it needs to be celebrated (except when they tried to walk it all back and say it was up to interpretation but it’s clearly not and they got blasted for it). In the first episode, Suletta says to Miorine after becoming the Holder: “B-b-b-but, I’m a woman . . .” to which Miorine casually replies, “I guess Mercury is pretty conservative . . . this is normal here.” It was a bold statement to lead with, and the series never shied away from what Suletta and Miorine mean to each other. "Witch From Mercury" breathes new life into the iconic Gundam franchise, and makes a great entry point for folks who have never even heard of a Gundam before.

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (Sony Pictures)

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (Sony Pictures)It seems that every piece of media nowadays is part of some bigger universe. Once a franchise clicks with audiences, the bird-brained executives running these media companies proceed to run a good thing into the ground by building these content universes. Franchises are made to be infinitely expandable and retcon-able so content can be produced in perpetuity (or at least until the money dries up). The Spider-Verse comic series is also a parallel world, multiversal, all-the-Spiderpeople-you-could-ever-want kind of situation, but at least for now, it all works up on the screen. Probably because the animation is absolutely fantastic.

“Across the Spider-Verse” is the middle film in what is (for now) a trilogy continuing the stories of Miles Morales and Gwen Stacy. Miles and Gwen visit different parallel universes each with its own Spider-Man and, in an inspired move, each with its own art style. Miles faces off against the Spot, the main antagonist of the film who has the ability to generate teleportation portals and who declares himself to be Miles’ rival. As The Spot’s power increases and Miles involvement with Spider-Society causes more anomalies in the multiverse, the stakes continue to rise. As someone who didn’t remember this was the second part of a trilogy, as the run time went on, I kept thinking, “How are they gonna wrap this up?” and then, “Oh boy they are gonna rush this ending . . .” before it really got to the end and I finally remembered “Oh, there’s another film coming.” This is two hours and 20 minutes that keeps up the tempo the whole way through, and ends at just the right spot to carry on next time with “Spider-Man: Beyond the Spider-Verse.”

The animation in “Across the Spider-Verse” is an exceptional labor of love. With each of the parallel worlds featuring their own unique art style, it does a lot to differentiate locations in the film. It gave animators some freedom to use the different art styles to express a wide range of emotions. The watercolor impressionistic styling used in Gwen’s Earth-65 to color the whole world in emotional energy, with everything giving off an aura of color, matching the mood, to really grab the viewer’s attention. Or the mostly black and white, thick-lined comic book style used when the Spot goes into his backstory. Or Spider-Punk Hobie Brown’s collage-inspired character design with his somewhat intentionally choppy frame rate (it was explained that for certain scenes Hobie was animated using less frames than the rest of the characters) giving his paper aesthetic an almost anime flavor by having his character animated less at times. This movie is a scatter shot of impressive technique and creativity, featuring the work of nearly 1,000 artists, but for how impressive the end product looks, this effort came at a cost.

“Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse” had an impact on animation this year because of the beautiful work done by the artists and animators – it is truly a standout film as a result. But the film also made waves for allegations of overwork, something that has impacted a number of productions in animation in recent years. In a year when striking workers have fought for better wages and better working conditions, folks in the animation industry have yet to be given their chance to seek improvements in their field.

This isn’t just a problem in North America, but in Japan conditions for lower level animators have long been deplorable. Extremely underpaid for the work they are expected to do, and working days on end without break, it is the worst kept secret that anime studios exploit their workers. One of the biggest offenders is Studio MAPPA, a studio that takes on several major projects each year. Animators working for MAPPA made the unheard of (in Japan at least) move to take to social media and air grievances about working conditions and insultingly low pay. One of the year’s biggest blockbusters is the series “Jujutsu Kaisen,” and as the show entered its second season, the high octane action depicted in the series came at the animators expense. Overwork hit hard, and while the end product looks great, it comes at such a cost we have to wonder if it is worth it?

In comparison, famed anime studio Kyoto Animation, the studio targeted by an arsonist in 2019, produced one show this year, the sublime “Tsurune” about a high school archery club. Kyoto Animation not only pays its workers a fair wage and has a strong policy against overworking, it also retains many of its talented artists and animators, helping develop their skills so they can advance in the industry. The model means less anime, but better quality. Not only for the end product, but for employees’ lives as well. As we’ve seen, animation is art. It is the creation of beautiful things by talented people. And the people that make it deserve better than being ground to dust under the weight of unfair wages and soul-crushing working conditions.

Vinland Saga Season 2 (Makoto Yukimura/Kodansha)

Vinland Saga Season 2 (Makoto Yukimura/Kodansha)Makoto Yukimura’s award-winning manga set in the Age of Vikings could have been just another glorification of the violent history from this time, but instead this setting is used as the backdrop for a reckoning with violence itself. How do we determine the value of a human life? Who is worthy of salvation? Is freedom from oppression and cycles of violence even possible? Yukimura implores us to think deeply on these questions.

This particular viking tale is centered around a fictionalized version of real life viking Thorfinn Karlsefni. In Season 1, Thorfinn is broken down and rebuilt as a fighting machine. Taken under the wing of Askeladd, a brilliantly written character and the leader of a mercenary band of vikings. Thorfinn plods along through 11th century England doing Askeladd’s bidding. He is exposed to, and commits, gruesome acts of violence as Askeladd and his merry men raid villages and slaughter innocent farmers. In Season 2, Thorfinn is sold off into slavery where he is dehumanized further, uttering the gut-wrenching line, “Not a single good thing has happened to me in my entire life.” Thorfinn is reduced to a state of nothingness. He wonders if it matters if there is any value in him living, or should he just give in to the abuse he suffers and die. Feeling this violence inflicted upon him, he begins to see just how much destruction he has wrought with his own two hands. He vows to escape his situation and begin a journey of not only self-healing, but a crusade to pull more people out of the cycles of violence that keep them perpetually marginalized.

“Vinland Saga” is a series that has been given an incredible amount of love and care from the team behind it. For its first season, the anime was produced by Wit Studio, a studio known for its polish and ability to extract so much from the source material it pulls from. They produced the superior first three seasons of “Attack on Titan” before Studio MAPPA took over. The same has happened here, with MAPPA taking the reins of "Vinland Saga." The concern around this change was warranted by fans, as MAPPA’s track record is spotty, but thankfully, a number of Wit Studio employees moved over to MAPPA to continue their work on “Vinland Saga.” Perhaps most important of all is director Shuhei Yabuta whose steady hand and clear passion for “Vinland Saga” has allowed for the series quality to not dip at all. This season of “Vinland Saga” is lighter on action, allowing for a focus on intimate moments between characters and details that the manga also highlights. There are shots of hands throughout “Vinland Saga,” something manga author Yukimura is transfixed by, with the author saying they reveal a lot about a character. The rough hands of a slave, the clean hands of a prince, the wrinkled hands of an old man who has seen so much.

Thorfinn is an incredible protagonist. His profoundly humanist vision for the future is idealized, certainly, but it is so hopeful, we want it for him and for ourselves. “Vinland Saga” so viscerally shows the cruelty that humans are capable of, how violence becomes systemic and wins out over even a shred of empathy, and the twisted justifications we use to be complicit in such violence. Thorfinn wants to find another way to exist. To create a world without violence, a world where people want to live instead of wishing for death. While his character was (intentionally) stifled at every turn in Season 1, here he is allowed to grow and as he begins to shape his own politics and worldview, every moment of struggle and tragedy he faces is felt so deeply. He confronts his past, and looks towards a brighter future, despite all he has been through. This is my anime of the year without question.

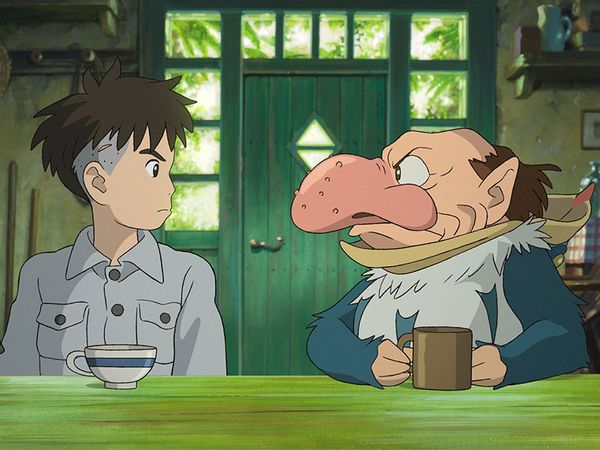

The Boy and the Heron (Studio Ghibli)

The Boy and the Heron (Studio Ghibli)At this point in his career, every film that Hayao Miyazaki makes could be his last, and no one is reckoning with this inevitability more than Miyazaki himself. He’s been in and out of so-called retirement since “Princess Mononoke” in 1997, but his recent works have grappled with notions of legacy and what we leave behind. While 2013’s “The Wind Rises” examines what happens to our life’s work when it is released into the world, and how little control we have over how it is interpreted, used and repurposed. With “The Boy and the Heron” Miyazaki seems to be searching for a philosophy to leave behind, this film being a letter to his grandson after all, on how to reclaim and nurture the self in a world that seems to just keep dragging us all along. While “The Boy and The Heron” is certainly . . . a title someone chose, the Japanese title “How Do You Live?” is truly the question at the heart of this story. It is Miyazaki at his most existential.

The film is set in the Japanese countryside during World War II, though war is not at the forefront, save for one harrowing scene that echoes through the film. War simmers in the background, a constant, subtle reminder that this is a world marred by violence. The low hum of the war machine is never fully out of earshot. After tragedy befalls his family, Mahito, the titular boy, leaves Tokyo and relocates to the country with his father to live with his aunt, Natsuko. Even in the rural locale, there is no escape from war. Soldiers march to the train station to join the effort, and Mahito’s father runs a factory making windshields for fighter planes — an autobiographical influence as Miyazaki’s own father built rudders for fighter planes, including the famed Mitsubishi A6M Zero.

When Natsuko goes missing, Mahito takes it upon himself to find her. This marks the start of Mahito’s journey into a messy, violent, somehow parakeet-filled, dream world of self-discovery, to perhaps find an answer to the question: “How do you live?”

As with any Studio Ghibli film, the animation on display is simply unmatched. The Ghibli house style has been refined to perfection at this point. Able to create beautiful, lived-in realities and fantastical unrealities that are overflowing with detail. Ghibli’s animators — after two years of pre-production and five years of full-on production — have delivered a film that is supremely confident in its aesthetic. The cohesiveness and vision of a Studio Ghibli film’s animation is one of its greatest strengths. Plus, the food has never looked more delicious. It must also be said that Joe Hisaishi’s score is also magnificent. Miyazaki’s long-time collaborator, Hisaishi often composes his pieces for Studio Ghibli’s films after looking at early storyboards and drafts, but in the case of “The Boy and The Heron,” Hisaishi was shown the nearly finished film, only a year ahead of its theatrical release. The results are themes that crescendo with precision, and in stretches with minimal dialogue — Mahito is a stoic boy, after all — Hisaishi’s pieces are able to carry the narrative wonderfully.

Hayao Miyazaki will be 83 in January. This could be the last film we ever get from him. Thankfully it is a wonderful film that is thematically dense, but can also be viewed lightly as a sort of “Spirited Away" but for boys. Miyazaki has been searching for a philosophy on how to exist in a world that has been corrupted. Perhaps there isn’t a way, perhaps we’ve already gone too far, but it seems he still thinks it is worth trying to find a way. Giving up on trying to change will only lead to more suffering, more oppression, more misery. It is easy to be dragged down into the abyss, to give in to misanthropy and nihilism, but Miyazaki, even after all he has seen in his life, still believes there is a way forward for humanity. It’s just no longer something he can do, so he’s leaving it to us to keep searching for it.

Read more

about this topic

Shares