Strong science, particularly vaccine development, helped us steer our way through the Covid-19 pandemic. Now, as the pandemic recedes, it’s time to hold drug companies accountable for the treatments they’ve developed. The evidence for these medications has not kept pace with major changes in the nature of the Covid-19 pandemic, and updated studies should be required to maintain approval for these very profitable drugs.

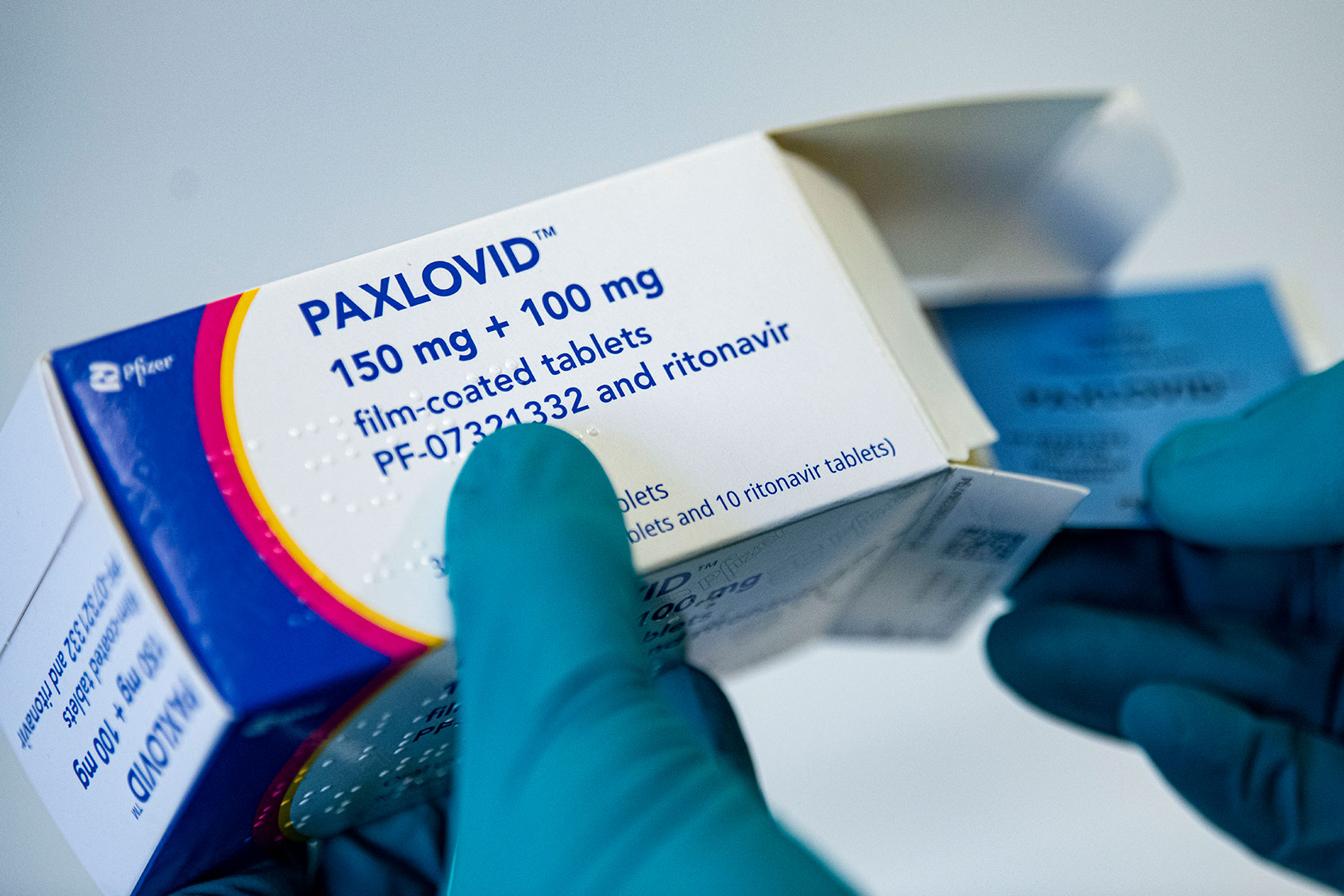

The Covid-19 drug development battlefield is littered with 479 failed or inactive drugs, while 358 are still in clinical or preclinical trials, according to a tracker maintained by the Biotechnology Innovation Organization, a trade group. The only oral Covid-19 therapy approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration that is recommended for first line outpatient use is Pfizer’s Paxlovid (nirmatrelvir-ritonavir), a two-drug combination that stops the SARS-CoV-2 virus from replicating in the body. Hailed as a game changer, Paxlovid is a very good antiviral drug that has saved many lives, and its incredibly rapid development was a feat of science. The major study leading to its approval, called the EPIC-HR trial, showed that it reduced the risk of hospitalization and death by an impressive 89 percent in high-risk, unvaccinated people.

But there is a lack of high-quality research on how Paxlovid affects outcomes beyond severe Covid — such as duration of illness, how the drug affects transmission, and whether it prevents long Covid. Nevertheless, some physicians are promoting the drug for these uses based on weak, inconsistent data. The stakes are high: If we fail to set a requirement for well-designed studies of Paxlovid’s impact on all concerns besides hospitalization and death, we will be setting up a slow-moving, disastrous recreation of mistakes made with drugs for other diseases such as influenza.

Early in the Covid-19 pandemic, the explosive, unorganized growth of clinical trials for treatments was intended to save lives from this fearsome new disease. But many trials were small and of low quality, with a few exceptional trials providing much of our good data. In that initial desperate push for Covid-19 treatments, experimental, everything-but-the-kitchen-sink approaches became widely used.

There is a lack of high-quality research on how Paxlovid affects outcomes beyond severe Covid — such as duration of illness, how the drug affects transmission, and whether it prevents long Covid.

The case of ivermectin is instructive: This antiparasitic drug was used in tremendous volumes based on poor quality and sometimes outright fraudulent data, despite advice against its use from the FDA and in formal treatment guidelines. Social media amplification of the increasingly dubious evidence base led to a near-delusional belief in its benefit — and impressive profits for some opportunistic doctors. A few well-coordinated and well-designed trials up front would have shortened the controversy, saved costs, and avoided duplicated effort of smaller low-quality trials. Most importantly, showing it to be ineffective earlier may have prevented the ensuing social media crusade, perhaps allowing some high-risk people to accept evidence-supported treatments like Paxlovid and the intravenous antiviral remdesivir rather than requesting, or even suing hospitals, to administer ivermectin.

Covid-19’s infection outcomes changed unusually rapidly across waves of the pandemic, which meant that studies could be outdated in months if they did not reflect the current viral strains and population immune responses. Data collection in the EPIC-HR study, which still guides treatment with Paxlovid, took place in 2021 when hospitalization rates were high, many were unvaccinated (including all trial participants), the viral strains were different than today, and the main outcome of interest in many communities was “flattening the curve,” or preventing hospitalization. Now, almost everyone has been vaccinated, infected, or both. In a recent study, 96.4 percent of U.S. blood donors had Covid-19 antibodies by September 2022. The overall risk of hospitalization and death has also decreased significantly.

Essentially, we are now dealing with a different disease. We are more focused on outcomes such as time lost from work, transmission risk, and long Covid risk. Yet there is almost no direct evidence about Paxlovid’s effect on these outcomes.

Paxlovid was approved for the treatment of mild to moderate Covid-19 in adults at high risk of developing severe disease. However, physicians and pharmacists have told me, it is increasingly being prescribed off-label for lower risk patients. This contention is supported by a recent U.S.-based preprint showing that 42 percent of more than 111,000 Paxlovid recipients had no major medical comorbidities, with treatment eligibility defined by having at least one risk factor for severe Covid-19. Some physicians are extrapolating from hamster studies and lab data to suggest it reduces Covid-19 transmission. And they’re prescribing it to reduce long Covid risk based on very weak studies that analyzed administrative databases for Covid-19 complications rather than tracking long Covid symptoms in treated and untreated patients.

This matters because Paxlovid treatment for people who are not high risk has not shown significant benefit. One still unpublished randomized trial of lower-risk patients was terminated because low rates of hospitalization overall (in treated and untreated people) made it impossible to see a benefit. Even in higher-risk groups, a recent meta-analysis of observational studies has shown very little absolute reduction of mortality, and no benefit in such patients under age 60. At the same time, people taking Paxlovid face possible side effects, drug interactions, and volatile drug pricing. They do not know if Paxlovid is worth all of that. They don’t know if the drug will reduce transmission to others, if they are less likely to get severely ill, if they will need time off work, or if it will spare them from long Covid.

Infectious diseases specialists like myself are experiencing an alarming sense of déjà vu. Tamiflu (oseltamivir), a treatment for influenza, was licensed in 1999 with data showing a modest benefit in reducing illness by one day. The reviewers noted that a “more definitive demonstration of clinical or public health relevance” would require additional data. But 24 years later, we are not farther ahead — important questions about Tamiflu remain unanswered, with longstanding debates about the benefit of the drug and a false advertising lawsuit that went on for nearly 10 years before being dropped in July. The guidelines for the use of Tamiflu in influenza vary tremendously because of varied interpretation of a poor evidence base, and newer studies call its use as an influenza treatment into question. Even so, in its first 15 years on the market, Tamiflu made $18 billion in sales.

It is hard to stop a prescribing practice once it has become the norm, despite inadequate data. This is a recognized driver of cost increases in health care.

Pharmaceutical companies play a pivotal role in the research and development of effective therapies, and their lifesaving contributions during the Covid-19 pandemic have been commendable. However, the major investments these companies make in R&D should not give them free rein to market high-cost, high-volume drugs of public health importance without continued scrutiny of their effectiveness if the initial registration studies no longer stand because of changes in the disease.

Some bold, novel options could help address this gap in evidence. In exceptional circumstances (such as pandemics), pharmaceutical companies could be required to conduct studies to reassess a drug’s effectiveness after it has entered the market if conditions have meaningfully changed since the initial trials. Another option could require companies to put a small portion of drug profits towards funding well-designed, independent trials so that crucial, commercially successful drugs would be part of ongoing studies. The FDA and other agencies should judiciously require and support such studies that could help guide treatment decisions, while balancing the need to support appropriate research and new drug development.

The medical community has responsibility, too: Professional societies that draft treatment guidelines must take a more consistently assertive stance in advising against uses for which there is insufficient evidence, rather than leaving it open to prescriber judgment. Both prescribers and potential patients need to accept and use evidence to help sustain health care systems, and lobby for changes needed to define the best treatments for people with Covid-19.

It is hard to stop a prescribing practice once it has become the norm, despite inadequate data.

We are at a unique juncture in the fight against Covid-19, as fear gives way to complacency — and the path forward is scientific rigor. Failing to mandate high-quality evidence for treatment choices may lead us back down the path of inadequately researched treatments, opinion-driven guidelines, and wasted resources.

Pfizer has raked in about $20 billion dollars in revenue from Paxlovid alone over the last two years. This sum is nearly half of the National Institutes of Health’s entire budget for 2022. It is not surprising that the company has not voluntarily started additional trials after approval based on the stellar results in that first, now-irrelevant trial.

In the wake of the pandemic, we have an opportunity to improve both what we are doing, and how we may address research challenges in a future crisis. Paxlovid’s price is set to increase — from $530 to $1,390 before insurance — next year, but there is no corresponding increase in our knowledge of its value. The cost of this information gap will be very high, for both individuals and health care systems.

Lynora Saxinger is a journalist, infectious disease physician, and professor at the University of Alberta who headed a Covid evidence synthesis group during the pandemic. She is currently a Fellow in Journalism and Health Impact at the Dalla Lana School for Public Health.

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.

Read more

about COVID-19