When you think of tails, cats, dogs and mammals come to mind — not exoplanets.

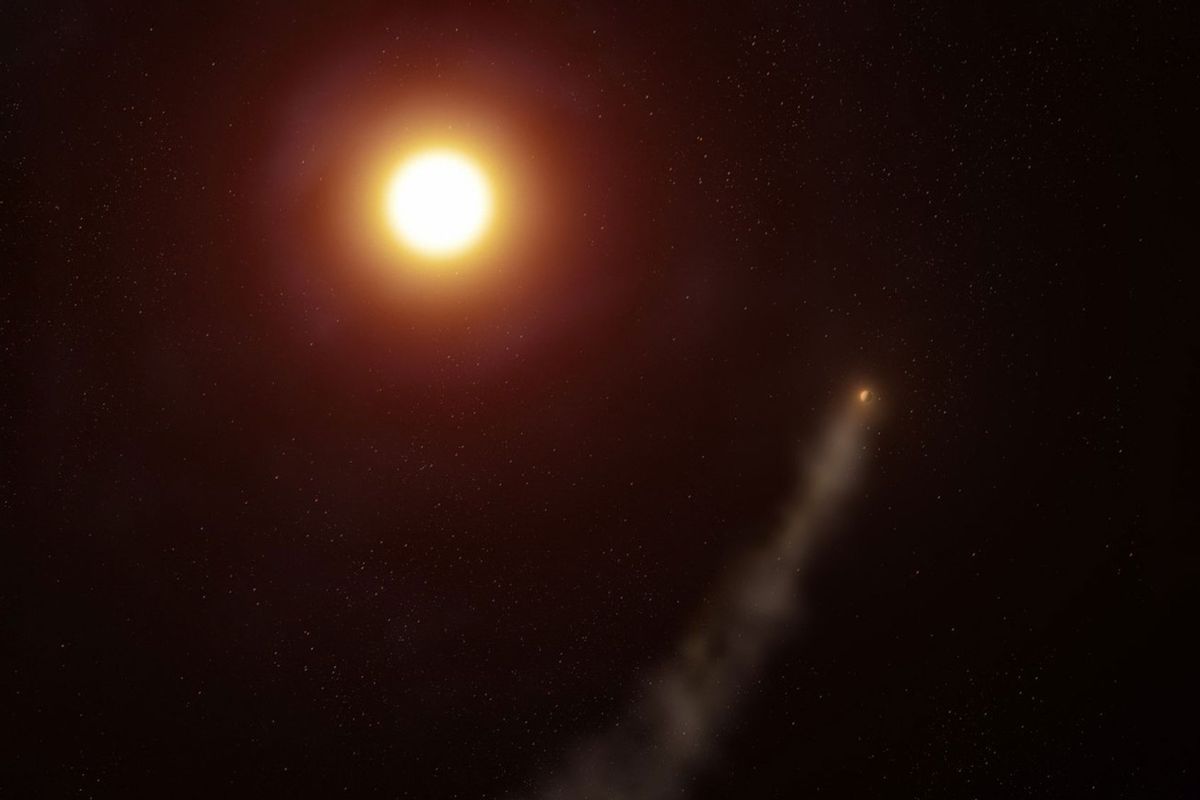

However, according to a new study published in The Astrophysical Journal, astronomers have discovered that a massive, gaseous, exoplanet in space has a giant tail. Known as WASP-69b — an exoplanet that is nearly the same size as Jupiter and located approximately 160 light years from Earth — it has a comet-like tail that trails the planet for at least 350,000 miles. Notably, the tail is essentially the planet’s atmosphere, which it appears to be losing.

“Work by previous groups showed that this planet was losing some of its atmosphere and suggested a subtle tail or perhaps none at all,” Dakotah Tyler, the first author of the research, said in a statement. “However, we have now definitively detected this tail and shown it to be at least seven times longer than the planet itself.”

The massive exoplanet was first discovered about 10 years ago. Astronomers famously nicknamed it “hot Jupiter,” in part because the exoplanet is so close to its host star that it makes a complete orbit in less than four Earth days. For comparison, in Earth’s solar system, Mercury has an 88-day orbit. Not only does the exoplanet’s close proximity to its host star affect its temperature, but also it’s essentially stripping away the planet’s atmosphere, leaving behind this massive tail.

Fortunately, the discovery of the tail is a win for science, as it may lead to further findings in astronomy.

“These comet-like tails are really valuable because they form when the escaping atmosphere of the planet rams into the stellar wind, which causes the gas to be swept back,” co-author Erik Petigura added. “Observing such an extended tail allows us to study these interactions in great detail.”

Shares