Depending on whose story you believe the most, Patty Hearst is either a victim, a bank robber, a kidnapper or a privileged white woman who found herself uniquely positioned to rebel against her family in a fashion so monumental that the recounting of it will outlive everyone involved.

Abducted from her apartment in Berkeley, California on February 4, 1974 by members of a small group of revolutionaries calling themselves the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), Hearst went from being known as the apolitical 19-year old granddaughter of newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst to, in just a few short months, a suspected willing participant in a string of crimes led by her captors; one of whom — Willie Wolfe — she was reportedly in a consensual romantic relationship with.

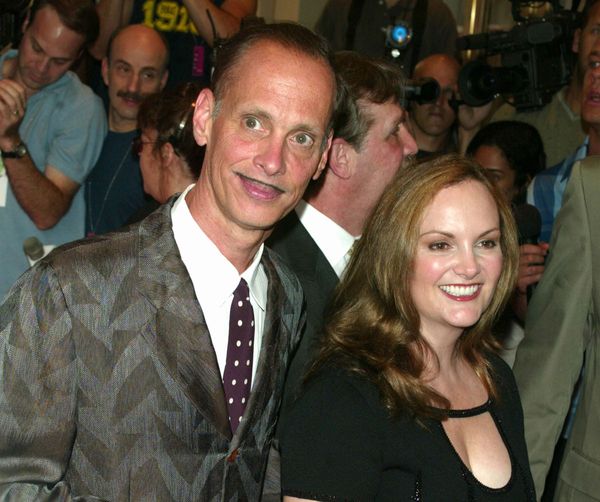

Fifty years have gone by since Hearst made the switch from Patty to "Tania" — the name she took on while enacting bank heists with the SLA — to Patricia, as she prefers to be called. And there remains a great deal of speculation as to whether or not Stockholm syndrome played a part in her sticking with the group for well past the point when she could have freely walked to the nearest police station to ask to be taken back home. In her own book, "Every Secret Thing," which she wrote after former President Jimmy Carter commuted her federal sentence in 1979, but before former President Bill Clinton granted her a full pardon in 2001, she opens up about the abuse she suffered at the hands of the SLA, her treatment during her trial, and the life she went on to live after. In the time between then and now, Hearst has carved out an existence of her own as a wife, a mother and an occasional movie star, having befriended director John Waters in 1988 and taken on roles in five of his films.

But her story is only one of many.

"This is a great window into what journalists do every day, which is not taking one person’s word for anything."

After reporting on the case since 1974, journalist Roger D. Rapoport's new book, "Searching for Patty Hearst: A Novel," tells all the other sides. Compiling firsthand knowledge gained from Patty's ex-fiancé Steven Weed — whom he lived with for a period of time after the kidnapping — as well as interviews with Coroner Tom Noguchi — tasked with inspecting the charred remains of the six SLA members who died in the LAPD firefight on May 17, 1974 — and Bill Harris — one of Patty's kidnappers and a founding member of the SLA — Rapoport puts it all in readers' hands and leaves them to draw their own conclusion on what the "true" story of Patty's Hearst kidnapping is. But, of course, assumption and perspective plays a hand in this regardless, resulting in what is still one of the biggest crime mysteries of our time. In an interview with Rapoport conducted over Zoom, he breaks it all down, including how piecing together these theories in the form of fiction allowed him to present them all in a way that's freshly entertaining for readers.

The following transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

The craft of your book and the fact that it’s a fictionalized way of recounting all of these theories, what did that allow you to present that you wouldn’t have necessarily been able to do were it purely a work of non-fiction?

Well, the limitation of non-fiction is that you basically are forced to stick to the facts. But as you’ve seen in this “true crime story,” who’s telling the truth? Who’s making stuff up? For example, if you wanna be an omniscient narrator, that’s great, but if you’re working for months and months with a guy who lived with her for three years (Steven Weed) and knew her from the time she was a 16-year-old high school student until she was a UC Berkeley art student and then later his fiancée, and he’s saying to you "I can’t publish this because it’s gonna get me in trouble," that really ties your hands. In other words, the publisher and the reader wanna know everything.

The other thing is that stress contaminates memory, so you can have two people in the same room telling completely opposite stories. So imagine this, you have eight people in a 1,200-square foot apartment living there for 53 days after the kidnapping, and Patty Hearst has a completely different version of the story than does Bill Harris, her kidnapper. It’s very very difficult to pinpoint who’s telling the truth and who’s got the goods. So the advantage of fiction is, you can give equal time to all the protagonists and let them tell their own stories. It gets a little harder when they’re not around, but through their history, through their writings, you can at least reasonably put together a fair picture. But I think it’s the conflict of disagreement between all the characters that helps the reader decide who’s telling the truth.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

How would you describe your book to someone looking to learn more about Patty Hearst and the details of her kidnapping? This anniversary will have her name in headlines again. And, I would imagine, put her in front of some young readers who may just be learning about her for the first time.

I’ve been doing some events, and the diversity in the group is quite amazing. There are a lot of young people — I’m talking people in college, even younger — who knew nothing of this case. Kind of a blank slate. I think what’s great for younger people is that they get to make up their own mind. They can read all of these conflicting accounts. And even if you’re not someone who watches a lot of true crime or reads a lot of true crime, I think this is a great window into what journalists do every day, which is not taking one person’s word for anything, and I think that’s all part of the creative process, but it’s also incredibly important right now because so much of what is coming out and is being read is filtered through a single voice. And the scientific method is never saying for sure that this is the final answer to the problem. And same in journalism, you have to look at all sides, and that’s what the book does.

Joan Didion and Stephen King both attempted to write novels about this case. And in Stephen King’s case, part of it morphed into a section of his book "The Stand," and in Joan Didion’s case, she wrote a book that never got published, so she published her notebooks called “South and West” about the case. So trying to see this through the lens of one protagonist or one kidnapper, it doesn’t work. You have to realize that, first of all, there were originally about a dozen members of the SLA, and then of course there’s Patty, her family, and in very short order she went from being a Hearst daughter, fiancée, a kidnapping victim, a kidnapper, then, in the middle of the kidnapping, the guy she fell in love with (Willie Wolfe) died in a firefight with the LAPD, then she fell in love with her bodyguard. So that’s a lot of transitions, a lot of families, and every one of those families has a story.

"She’d always been kind of a rebel."

When she went to jail, she was really in the custody of her lawyers so to speak, because they were the ones that were calling the shots. And her family hired the most famous criminal attorney in the country, F. Lee Bailey, and one of the psychiatrists he brought in had worked with another one of his clients, The Boston Strangler. So you can imagine, she’s now being psychoanalyzed by the psychiatrist who worked on the Boston Strangler case. So all this is going on, and they’re kind of coaching her on what she’s going to say and what she’s not going to say. Meanwhile, her lawyer, when he signed the fee agreement with the family had a clause inserted that Patty had to sign that said when she writes her book she’ll agree not to publish it until 18 months after he publishes his book, in exchange for a discount on his fee. He loses the case, and his book contract is canceled. So there’s all these different motivations, and whether or not she was a terrorist, a bank robber, a kidnapper or whether she was a victim of brainwashing, I think that’s where readers get to decide and make up their own mind.

I was born in 1977, so I grew up knowing about the Patty Hearst case after the fact. But my initial impression of it, which is a hard one to shake, Is that she was a rich white woman living in the Bay Area who found herself in a situation where she could rebel from everything she’d previously known and go wild for a bit and she took it. So having reported on the events of her kidnapping, and now writing this book, what’s your opinion on that still being a very common take?

Well, here’s something that most people don’t know about Patty Hearst. She wasn’t just a rich white girl about to get married in a society wedding. In fact, that’s the how the SLA discovered her was they saw her wedding announcement in the paper and they were broke and wanted to get attention in the media and get people thinking about the war in Vietnam. Patty wasn’t just apolitical; her father, who was considered to be a fairly conservative publisher, was actually to the left of her. She walked through a United Farm Workers picket line, she was at a junior college where there was a student strike and she went to class. She made fun of her father who was doing some work in the Latino community to get computers in schools that couldn’t afford them and Patty thought all that was ridiculous. And to the right of her was her mother, who was a conservative University of California regent, who actually took her on a roots trip back to Atlanta and was using the N word. I mean, so there was this big disparity. So when her father failed to ransom her on the advice of the FBI, the attorney general and the governor, she took it very badly and announced that she decided to stay [with the SLA] and fight. Her mother was furious about the father not paying the ransom, and it ultimately led to their divorce.

Patty had been fed a lot of propaganda by the SLA, but she’d always been kind of a rebel. In the Catholic private schools as a young girl mouthing off to the nuns. She was always a bit impudent. So when she made her announcement, a lot of people said "Oh no, this is just the SLA crafting dialogue for her. She’s obviously been brainwashed." So [Patty and the SLA] went out and robbed a bank. And not just any bank, but a bank owned by the father of a childhood friend. So that really took her from being a charity case into being a very very shady character. That really affected the reputation of the Hearst family dramatically.

John Waters, writer/director of original film, & Patricia Hearst attend of the opening of 'Hairspray' on Broadway, New York, 15/08/2002. (Jim Spellman/WireImage/Getty Images)Patty has a famous quote that I’ve always found fascinating where she says, "I finally figured out what my crime was: I lived, big mistake." This brings to mind other women who have walked away from their own crime cases such as Gypsy Rose Blanchard, Amanda Knox, Leslie Van Houten. And they went on to live lives forever associated with the crimes they’re tied to. So compared to them, would you consider Patty Hearst to be a survivor? And what’s your read on that quote of hers?

John Waters, writer/director of original film, & Patricia Hearst attend of the opening of 'Hairspray' on Broadway, New York, 15/08/2002. (Jim Spellman/WireImage/Getty Images)Patty has a famous quote that I’ve always found fascinating where she says, "I finally figured out what my crime was: I lived, big mistake." This brings to mind other women who have walked away from their own crime cases such as Gypsy Rose Blanchard, Amanda Knox, Leslie Van Houten. And they went on to live lives forever associated with the crimes they’re tied to. So compared to them, would you consider Patty Hearst to be a survivor? And what’s your read on that quote of hers?

"There’s no question that privilege was part of this."

She is a survivor. However, there’s absolutely no question from day one in this case that she was treated differently from other women who have been in similar revolutionary situations. Sara Jane Olson, who was actually Kathy Soliah, one of the SLA members, they found her years later in Minneapolis, she was an actress and had been married to a doctor. She was one of the SLA members involved in one of the bank robberies. She didn’t actually pull the trigger on the woman who was bringing in a church collection who died, or anything like that, but she went to jail. Patty, who drove one of the getaway vehicles, not only did she not go to jail, not only was she not prosecuted, but there was a civil case brought about by the family of the woman who died, and Patty’s dad cut a check for a settlement. So the guy who didn’t wanna do the ransom was pleased to do this out of court settlement. In the jury selection, the Hearst family was allowed to sit in on the jury selection for the bank robbery case. So there’s no question that privilege was part of this.

Similar to Gypsy Rose, who got early release and then dove right into the media aspect of things, Patty kind of did the same thing. She wrote her book, she starred in those wonderful John Waters movies. Didn’t it seem like it would occur to her that doing this would hurt her chances of every being seen as anyone other than that image of the woman in the beret with the gun?

Right. Well one of her daughters played Abigail Folger in a movie about the Manson murders, so it even goes farther than her. But here’s a question I’ve thought about a lot, because obviously the decision not to ransom her made her really vulnerable. And when she realized they weren’t going to ransom her, the SLA said, "Look, if you wanna just walk you can walk." They gave her a gun while she was in captivity. There was one point where after the shoot-out where Willie Wolfe died and so on, they were kind of on the run and they were on a beach in San Mateo County and a park ranger came and helped her with a sling to help lift her off the beach because this hill that they’d gone down was too steep and very rocky. And when they lifted her up to safe ground, she could have just said, "Hi, I’m Patty Hearst. Take me away." So there were all these opportunities, and that really really clouds her story. But the point of the media thing, the Hearst family had obviously been a victim. They had to run all of Patty’s communiques from the SLA on the front page of their papers and so on, and the whole damsel in distress narrative that her grandfather created to build circulation over the years — the kind of women you’re talking about, white women somehow kidnapped or taken in these captivity narratives by Native Americans or Black people, kind of the Ku Klux Klan recruiting narrative — well that was a huge circulation builder. And suddenly they, after merchandising it and marketing it for years, suddenly one of their own is at the heart of the story. So Patty decided to flip it back, and I think you’re absolutely right, that clearly, to this day, raises a question about how at one point she’s spouting all this revolutionary rhetoric and the next day she’s saying it was all made up.

How do you explain this? And this is part of what happened in the trial. F. Lee Bailey had watched "The Manchurian Candidate" and he was fascinated by the whole idea of brainwashing, but, during the trial, New Times, the magazine I was writing for, ran another article pointing out that in her purse when she was captured was an Olmec monkey carving that had been given to her by Willie Wolfe, who had been wearing an identical carving as a necklace. So why, a year and a half after this guy died, was this carving from her lover in her purse? A lover who she claimed in the trial that he’d abused her. And during the trial, they took that out of her purse from a police locker and showed it to the jury, and that really undercut her credibility.

The Hearst family, to the best of Rapoport’s knowledge, has decided as a family and as a company that they’re not going to be talking during the 50th anniversary.

Shares