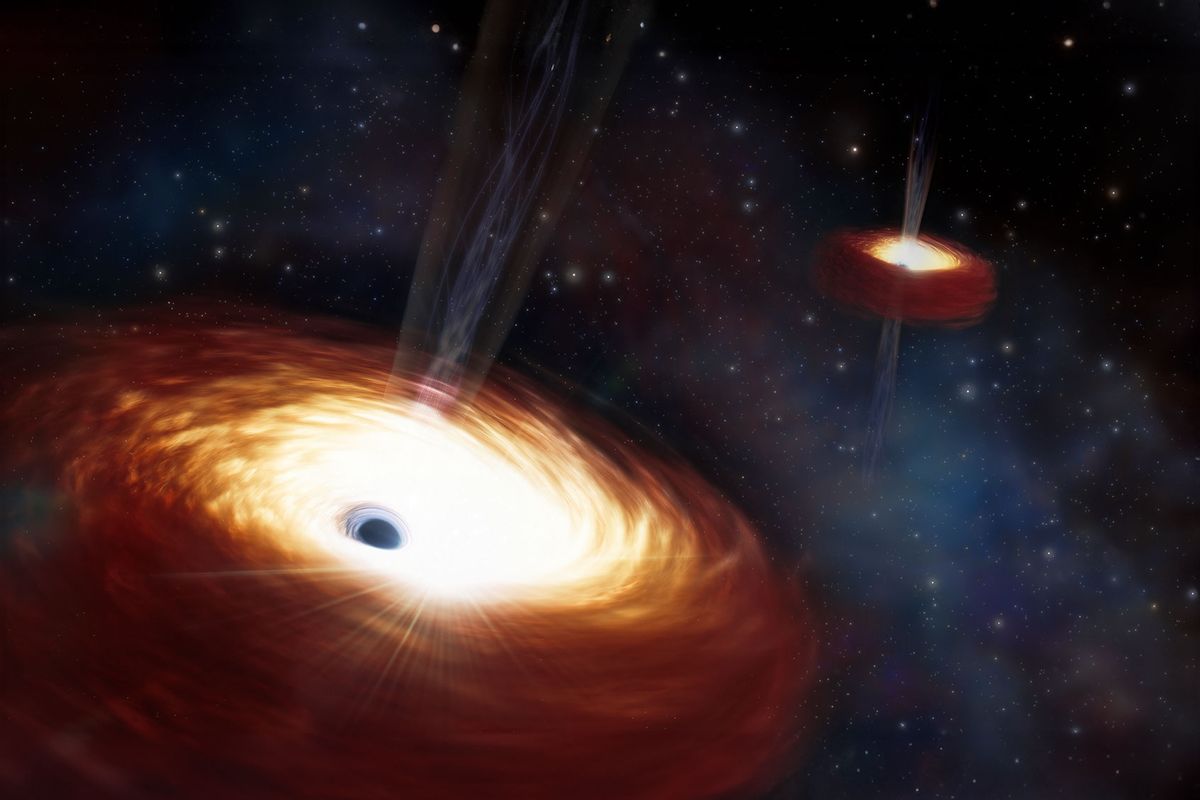

Black holes are some of the most powerful, destructive and massive objects in the known universe, devouring stars at unimaginable speeds and ripping them apart with such ferocity that they discharge luminous flares visible from millions of lightyears away. When black holes collide into each other, they produce gravitational waves, as scientists learned in 2015 after recording a pair of stellar-mass black holes colliding for the first time. One can only imagine the spectacle that would ensure if a pair of supermassive black holes (which are much larger) collided into each other. Unfortunately for astronomers and astronomy aficionados alike, scientists have never detected such a merger... and a recent study of the heaviest pair of supermassive black holes ever measured may help explain why.

Published by a team of American scientists in The Astrophysical Journal, the study analyzes "one of the most massive black hole systems known," a binary located within the elliptical galaxy B2 0402+379. It is not unusual for two black holes to get bound in orbit with each other after galaxies merge; when this happens, they are known as a binary pair. In theory, binary pairs should inevitably merge with each other, but a look at the largest supermassive black hole binary pair ever measured — 28 billion times more massive than our Sun —shows how supermassive black holes could render that impossible because of their sheer immensity.

These two supermassive black holes are about 24 light years apart. But the researchers estimate they've been locked in at this distance for three billion years. The merger is stuck. In order for the supermassive black holes to get as close to each other as they did, they needed an unusually large number of stars, and consuming them scattered almost all of the nearby matter out of the galaxy's core. Without stars and gas to consume, the collision is as stalled as a truck without gas.

“Normally it seems that galaxies with lighter black hole pairs have enough stars and mass to drive the two together quickly,” Roger Romani, Stanford University physics professor and co-author of the paper, said in a statement. “Since this pair is so heavy it required lots of stars and gas to get the job done. But the binary has scoured the central galaxy of such matter, leaving it stalled and accessible for our study.”

Shares