If you want to believe one of the more dubious claims concerning the influence of the 1980 adaptation of “Shōgun,” Americans may thank the production for bringing sushi to middle America.

This apocryphal trivia hasn’t been entirely debunked; it’s more accurate to say that it is roundly doubted. Never mind that Japanese dining establishments like Benihana had been wowing Americans since the mid-'60s, or that sushi as we know it didn’t appear until the 1800s. ("Shōgun" is set in 1600.) The allegation’s source is the behind-the-scenes documentary “The Making of Shōgun.”

Given the times in which NBC’s adaptation of James Clavell’s novel aired, however, that detail feels true even if it isn’t.

The 1980 miniseries was the first to bring a highly fantasized version of Edo-era Japan to American primetime television by way of a production filmed entirely in Japan. It went on to win a Peabody Award along with several Golden Globes and Primetime Emmys, including for outstanding limited series, along with giving Richard Chamberlain’s career a second wind.

Looking back on America’s 1980s fixation with Japanese popular culture, one might be tempted to theorize that “Shōgun” seeded that obsession. The late Tom Shales, who reviewed the series for The Washington Post, wagered that “[the] serial may in fact constitute the first great wave in the Easternization of the '80s and it could do much to popularize or re-popularize Oriental culture and fashion here.”

If you couldn’t tell from his usage of an offensive descriptive term in that sentence, 44 years ago was a very different time. (A British New Wave band called The Vapors already had a hit with the speedy “Turning Japanese” months before the miniseries premiered. Cultural sensitivity was not exactly at an all-time high.)

But Shales couldn’t have predicted how lasting in popularity “Shōgun” would turn out to be.

“Shōgun's" debut coincided with a strike by the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) and the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (AFTRA) that had run since July. Meaning, it didn't have much competition on that fall's TV schedule.

Even if there were, by that era’s standards the miniseries' cinematography was dazzling, and the brutality, which challenged broadcast standards to a high degree, was unlike anything that had aired before. American TV dramas long depicted violence, but not beheadings. Sexuality was implied, but women didn't go topless; this miniseries flashed bare breasts.

For five nights in September of 1980, if you owned a television, it was probably tuned in to “Shōgun” at some point.

Since the VCR wasn’t as ubiquitous as it would be a few years later, relatively few horndogs were rewinding to ogle those moments. But a lot of people took them in. Nearly 33% of households with TVs watched all or part of “Shōgun,” giving it the second-highest rating in TV history after ABC's “Roots,” which was broadcast in 1977.

Like that telecast, NBC put “Shōgun” on the air outside of sweeps, although it intended to draw more attention instead of burying it, as ABC’s top executives sought to do with “Roots” by having it air over eight consecutive nights in January.

Presenting its top miniseries as the opening salvo in its fall season worked. For five nights in September of 1980, if you owned a television, it was probably tuned in to “Shōgun” at some point, if not for the entire run.

As is the case with most pop culture curiosa, “Shōgun” only deserves partial credit or blame for escalating America’s fetishizing of Japanese style and customs. In truth, its premiere coincided with an enthusiasm that was already rising by the time we watched it.

Actor Richard Chamberlain and actress Yoko Shimada on set of the mini-series "Shogun" , circa 1980. (Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)It’s not as if Americans hadn’t been regularly exposed to Japanese culture, products or ideas before. The summer before, NBC News aired "If Japan Can . . . Why Can't We?" which endeavored to demystify the reasons for that country’s famed productivity. During the same September that “Shōgun” came to TV, PBS featured five programs from its public broadcaster NHK.

Actor Richard Chamberlain and actress Yoko Shimada on set of the mini-series "Shogun" , circa 1980. (Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)It’s not as if Americans hadn’t been regularly exposed to Japanese culture, products or ideas before. The summer before, NBC News aired "If Japan Can . . . Why Can't We?" which endeavored to demystify the reasons for that country’s famed productivity. During the same September that “Shōgun” came to TV, PBS featured five programs from its public broadcaster NHK.

For many years before that, American and Japanese filmmakers had engaged in tacit cultural exchanges over the post-World War II era. Cinephiles already revered director Akira Kurosawa, who featured “Shōgun” co-star Toshiro Mifune in his famous Edo-era set jidaigeki films including "Rashomon," "Seven Samurai" and "Yojimbo." These works and other paid homage to American directors such as John Ford.

American audiences of the ‘60s, ’70s and ‘80s were amply exposed to other Japanese entertainment, mainly giant monster rampages epitomized by the 1954 movie “Godzilla” and its resulting sequels.

Since being syndicated to the U.S. in the mid-60s onward, American kids watched the adventures of, among others, “Ultraman,” “Spectreman” and “The Space Giants” after school.

These shows and movies reflect a post-war, industrialized, atomic-influenced vein of storytelling with none of the flirtation “Shōgun” foregrounded narratively and stylistically.

Then again, the miniseries also featured sword fights and ninja assassins, both of which still top the list of boyhood fantasies and inspire legions of would-be Karate Kids to this day. Each also figures centrally in many video games. The lineage of Sony Interactive’s lushly rendered “Ghost of Tsushima” may draw direct links to Kurosawa’s oeuvre, but if the swooning romance of its visuals and haiku interludes draw us in, I’d argue that’s a mild symptom of Clavell’s influence.

We need your help to stay independent

It’s impossible to place a concise count on the number of business school graduates who decided mounting katanas on the office walls was cool – it never was. Sadly, it was a thing for a while which, again, is less the fault of “Shōgun” than the result of an industrial shift.

When the American auto industry was in a slump in the early ‘80s, Japan’s economy was ascending. With the Reagan administration capping the number of vehicles allowed to be imported to the United States, Japanese automakers responded by moving a portion of manufacturing to the United States.

Like other fleeting trends of the '80s and '90s, our subsiding infatuation was followed by our embarrassment.

Honda began manufacturing automobiles at its Marysville, Ohio plant in 1982. Nissan’s first American-made cars rolled off the line in 1983; Toyota’s in 1986. Along with Sony, Casio and other brands we now see as commonplace, these companies’ functional entry into American life exposed more working and middle class employees to Japanese business culture, along with insinuating bastardized samurai lore into Western interpretations of the so-called Japanese business mindset.

So: Want to trace the origins of white-collar douchebaggery epitomized by, say, some of the choicest employees of the fictional Nakatomi Corporation of “Die Hard” to a source? Start there.

The perceived impact of “Shōgun” on fashion might have a stronger case although, again, many experts would argue that a group of Japanese designers including Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons and the late Issey Miyake were already changing couture.

“[T]o many historians the exposure of modern ‘Japanese fashion’ to a suddenly more accepting international audience was intrinsically tied to the rise of Japan as an economic force in the 1980s,” observed Melissa Marra-Alvare, an assistant curator of research for the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, in an article about the Japanese influence on fashion.

She went on to cite the “cultural exoticism depicted in author James Clavell’s bestseller ‘Shōgun’” as adding to America’s fixation on Japanese culture. This is true: in the weeks leading up to its adaptation’s TV debut Clavell’s book could be found in nearly every grocery store across the United States, and in the years afterward you could find piles of their paperback version at second-hand bookstores and used book fairs.

But like other fleeting trends of the '80s and '90s, our subsiding infatuation was followed by a collective embarrassment. Hence, when FX announced in 2018 that “Shōgun,” the prevailing murmured sentiment at the time was that the network was courting disaster.

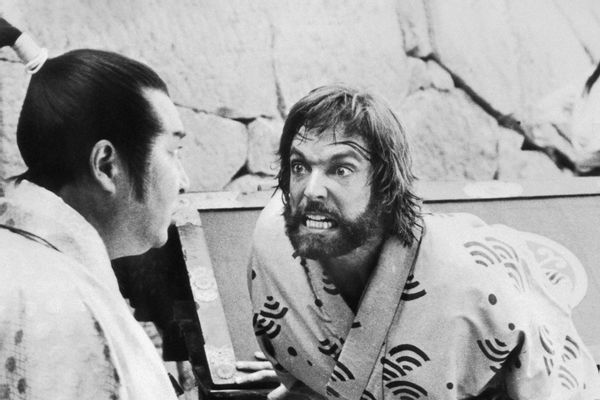

Richard Chamberlain and Nobuo Kaneko in the 1980 miniseries "Shogun" (Getty Images)Its sins are what we remember best. Women depicted in “Shōgun” are highly sexualized, both in Clavell’s 1975 novel and the broadcast version. Chamberlain is written as the quintessential white savior, the “one man [who] has the power to change Japan’s destiny,” as a cable channel commercial describes. It’s no wonder that Japanese audiences couldn’t stand it when it first aired there in 1981.

Richard Chamberlain and Nobuo Kaneko in the 1980 miniseries "Shogun" (Getty Images)Its sins are what we remember best. Women depicted in “Shōgun” are highly sexualized, both in Clavell’s 1975 novel and the broadcast version. Chamberlain is written as the quintessential white savior, the “one man [who] has the power to change Japan’s destiny,” as a cable channel commercial describes. It’s no wonder that Japanese audiences couldn’t stand it when it first aired there in 1981.

But we’ve also benefited from what its success inspired. More than its predecessors, “Shōgun” ushered in the age of can’t-miss miniseries exemplified by “North and South,” “Lonesome Dove” and Chamberlain’s other best-known limited series star turn, “The Thornbirds.”

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Four decades later, FX’s refreshing revisit from the perspective of its Japanese characters drew 764,000 same-day viewers for its on-air premiere, an audience that expanded to 9 million streaming views globally on Hulu, Disney+ and Star+.

These totals reflect a whole new world of television in which the 10-episode limited series competes not with two or three other channels but hundreds of episodes across dozens of channels and platforms, and a streaming view is defined by a formula: total viewing time divided by running time.

It’s also breaking through in a time when American audiences can choose from a broad variety of series and films from Asian countries; Japan is but one. We are fortunate to live in an era when a new “Shōgun” invites informed discussions about its filmmaking techniques and storytelling instead of gawking at its supposed foreignness. And it does make a person hungry for more limited series like it. Other cravings are entirely coincidental.

New episodes of "Shogun" premiere Tuesdays on Hulu and air Tuesdays at 10 p.m. on FX.

Shares