The PTSD that comes with living through weekly shootings, teenage funerals and that third-world American experience in general makes phone alerts scary. This is what happens when you grow up in a rough environment. A phone chirping and glowing past 1 a.m. is a horror film scene because you know that no good news is waiting on the other side.

I was in bed reading myself to sleep, my wife next me, "Law and Order: SVU"-ing herself to sleep, when my phone buzzed and buzzed. Not again, I thought.

“Who is that?" she said, well aware of my trauma and the bad news that hunts me.

I picked it up, punched the text bubble and gave a quick skim. No one is dead.

“There's a Freaknik documentary coming out,” I laughed. “The young kids don’t want to see their moms twerking, and my older homies don’t want to caught acting crazy on camera.”

We giggled and dozed off. I already knew the doc was coming but got a kick out of some of the reactions in my group chats. As a collective, everyone was excited about the film.

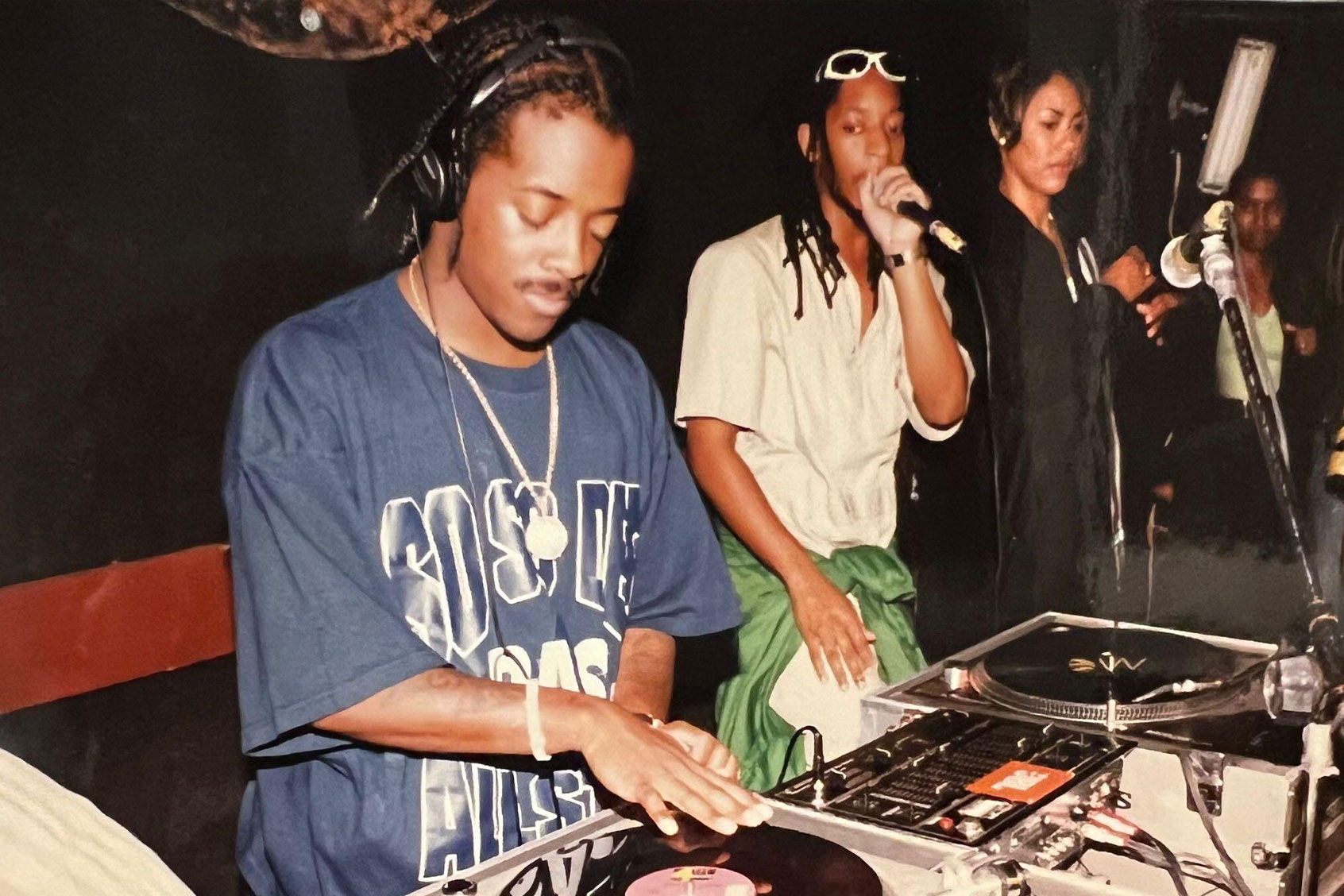

Hulu has since released "Freaknik: The Greatest Party Never Told," the Mass Appeal P. Frank Williams-directed documentary. Freaknik started in the '80s as a small outdoor party for Black students in Atlanta who couldn't always afford to travel home over Spring Break but quickly grew into a cultural phenomenon, big enough to shut down the entire city by the '90s. Industry heavy hitters and hip-hop legends Luther Campbell and Jermaine Dupri are among the film's producers. The two also appear on camera and take us down memory lane, to before we had iPhone apps, Eventbrite or group chats that made us aware of the parties. This was truly an era where you had to be in the know or risked being left out. I didn't get a lot right as a child, but I was always in the know.

* * *

“Yo, y'all wanna roll down Freaknik? We tryin' be like 40 deep down there,” Hawk said to me, DI and Willie. Hawk was an older guy from these projects where I used to like to play basketball. He was a trendsetter, a street philosopher on government conspiracy theories, most importantly, he was fly. That dude had all the new Jordans first, introduced us to Avirex leather jackets but scolded us if we wore Avirex clothes, because “they only make good leather coats and nothing else.” He even had access to lookbooks and catalogs. Who had access to lookbooks and catalogs from designers back in the '90s? Hawk did, that's who.

I was 16. Willie was two years younger and greener than a frog holding a cucumber. DI was one year older than me and maybe more mature than us all. He wasn't trendy. He wore Timberlands all year round and constantly listened to music. It's kind of like music was the only thing that would allow him to function.

DI didn't really have structure. He lived with his mom, but she had her own issues that didn't require clocking a 17-year-old. Besides, where we were from 17 was a man anyway, at least to the system.

“We gotta go. I heard Atlanta was crazy,” DI said.

“I can’t,” Willie answered instantly. “My grandma would flip out.”

“You can’t do nothin',” DI spat back. “Like come on, man. You gotta grow up at some point!”

I quickly said I was down before it turned into a thing. The three of us came from three different kinds of households. While I had parents who sometimes required explanations for things like me venturing to Atlanta, I also had freedom. The freedom to stay at a friend's house for extended amounts of time, the freedom to not call or check in daily, the freedom for me to shoot to Atlanta, and get back without anyone noticing. DI didn't really have structure. He lived with his mom, but she had her own issues that didn't require clocking a 17-year-old. Besides, where we were from 17 was a man, at least to the system.

Willie was being raised by his grandparents. His mother had a new man she started a new family with. His grandparents were strict, like overseers on a slave plantation — he couldn't really go anywhere, stay out too late or wear anything too flashy. So I knew he wouldn't be going down, and a conversation about him participating would be a tremendous waste of time.

“There’s no time to bulls**t,” Hawk said. “Y'all gotta be ready because you gonna see the girl of your dream 1,000 times in one weekend. So many dream girls, you won’t have a dream girl anymore.”

Willie stomped off. DI and I grew evil grins.

Freaknik: The Wildest Party Never Told (Hulu)A few days later, our trio was chilling on the block, talking Freaknik, when Hawk and light-skinned Desmond, who we called Des, walked over.

Freaknik: The Wildest Party Never Told (Hulu)A few days later, our trio was chilling on the block, talking Freaknik, when Hawk and light-skinned Desmond, who we called Des, walked over.

Des, who was my age, had attended with Hawk and those older guys a year before. He couldn’t stop talking about Freaknik. He didn't have a car his first time out, but now owned a gold Acura Legend with gold BBS rims and peanut butter-colored leather. He also had custom sheepskin chair covers for the front and back. Those Legends seated four to five people comfortably. I told him I had all the gas money, if me and DI could roll down with him.

“I wanted you to come anyway, boy, keep ya money,” Des laughed, waving a wad of cash at me. “Just bring your best fit, because you will never see this amount of badass girls all together in one spot.”

Des explained Freaknik as a Mecca of beauty. A place where our smarts and looks or the amount of game we had didn’t matter because there were so many women. Tall women, short women, genius women, fun women, serious women — every shade of Blackness, in bikinis, in booty shorts, in love, in lust with us. Writing this now feels awful, and out of control. But you must remember this was 1996. I was 16 and as tall as I was gullible.

“You see, most guys who go don’t have money,” Des continued, waving his cash, digging into his sock to reveal another fluffy green stack of bills. “They be sleeping on people's couches and in tents like bums. We gonna have 10-star luxury suites with champagne and all that!”

My eyes widened as Willie buried both of his hands deep into his palms, and said something like, “Man, f**k my grandparents!”

I can’t remember my actual response, but I probably agreed with him, which was messed up because his grandparents did the best they could. 1996 was an extremely violent year in Baltimore City. If you weren't using drugs coming, then you were selling them going as you floated in between the 333 homicides that happened in our small city that year. Honestly, Willie's grandparents were just trying to protect him the best way they knew.

* * *

Fashion was the first and maybe the most important step for this big trip. There was no online shopping or social media, and the trends didn't run together like they do now. You dressed based on what was sold in your region. Our region was big on Guess jeans, Boss, Polo by Ralph Lauren, Nautica and Tommy Hilfiger. As far as sneakers, we always rocked Air Jordans, Nike Uptempos, Nike Air Max and New Balance. DI and I, both street kids, both with pockets full of street money, went to Downtown Locker Room, Macy’s and Hecht’s and blew thousands on our outfits. We were ready.

Well, I was ready. DI got booked for drug possession a few days before we were supposed to leave. Spring Break rolled around, and I was in the back of Des’ Legend next to a stranger that Hawk stuck with us. Des was behind the wheel, and his cousin who didn't speak much, sat in the front holding a map.

It was easy for me to sleep, because Des was the best driver, especially to be so young. He drove us to New York often, where we’d use to get our Pelle Pelles and now Avirexs. The previous summer he drove us from a basketball tournament in New York all the way down to Virginia Beach, and still had enough energy to party as soon as we pulled up to our hotel.

Hawk’s plan wasn't perfect, because we weren’t 40 deep, but there were about 12 guys from East and West Baltimore linked up and headed down 95 South to Atlanta. It should be about a 10-to-11-hour trip if you are only stopping for gas and bathroom breaks, but we were young and immature, so we drank too much, stopped too much, burned down the fast food stands at rest stops then did it over and over again. None of our stops were coordinated; you’d think everyone would go to the bathroom at one particular exit, but we couldn't get it together. We complained to each other about the frequent stops but never stopped stopping.

The new documentary gave me a chance to relive that trip, making me realize that we've probably spent more time in the car than at wild parties.

Des’ sound system and 12-disc CD changer was my favorite part of the trip, because Nas had music out and Biggie had music out and Wu-Tang had music out and Tupac had music out and Mobb Deep had music out and AZ had music out. I imagine we had to sound like a ghetto chorus as we gunned down the highway because we knew all the words to "Ready to Die," and all the words to "Doe or Die," and all the words to "If I Die 2Nite." And we sang and sang and sang. DI would’ve been in heaven, just by being on the open road and zoning out to our favorite artists. Instead, he was in a cell.

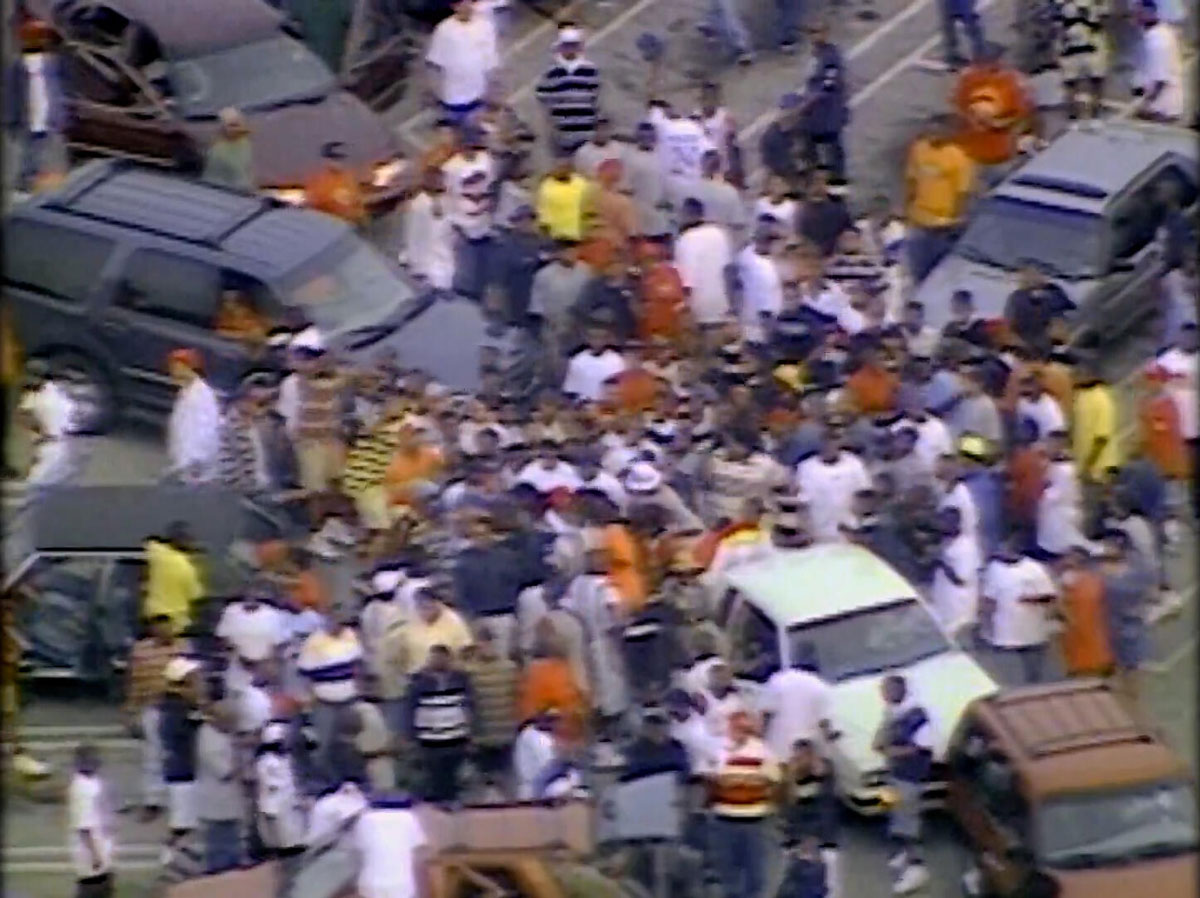

Unfortunately for us, a lot of singing would occur, because we arrived and saw that Freaknik should have been called Trafficnik. The only cool thing about being stuck in traffic was sometimes girls would jump on the hoods of cars and dance for those of us who could do nothing but inch forward down along the busy streets.

The new documentary gave me the chance to relive that trip, making me realize that we probably spent more time in the car than at wild parties. I do remember the Olympic signs all around town, but we had no idea at that particular time what that could have meant to our trip. As a character on the documentary put it, and I'm paraphrasing, “Freaknik brought millions to Atlanta. The Olympics will bring billions.”

Some people in the film credited Atlanta winning the bid to host the 1996 Summer Olympics with the beginning of the end of Freaknik. The party used to take place at Piedmont Park until popularity and outsiders from around the country made it a citywide thing. To combat the traffic from Black outsiders, the city of Atlanta attempted to block off many exits, which caused the nightmarish traffic.

Freaknik: The Wildest Party Never Told (Hulu)But I would say that our presence played a major part in Freaknik's decline as well, because I wasn't supposed to be there. According to the film, and the founders of the event, Freaknik was a party hosted for college students who couldn't afford to go home over Spring Break. It grew into a destination for Black college students across the country while remaining fun and innocent as it was sexy.

Freaknik: The Wildest Party Never Told (Hulu)But I would say that our presence played a major part in Freaknik's decline as well, because I wasn't supposed to be there. According to the film, and the founders of the event, Freaknik was a party hosted for college students who couldn't afford to go home over Spring Break. It grew into a destination for Black college students across the country while remaining fun and innocent as it was sexy.

So how does a pack of teenage drug dealers, drug dealer affiliates and street runners — who had no plans of attending college at the time and thought all of that Greek life stuff was the corniest thing anyone could ever do — end up at this party? The answer is simple: nothing sells like the combination of sex and beautiful people who are looking to have a good time. We were told that took place in Atlanta over Spring Break, and we all wanted in.

My very presence, I believe, helped turn Freaknik from a healthy gathering of young intellectuals into I don't know what. I didn't have a gun on me, but I'm 1000 percent sure some of my friends did, and some of them were always eager to use them. Baltimore had a reputation for being a city of gunslingers, and some of those guys were very excited about keeping that stereotype alive and well.

When we finally got out of traffic, we found our way into a few parties. I will say that Des wasn't lying. Freaknik was the Mecca of beautiful women who all seemed to have one thing in common: They were all out of my league.

These cultured women were dancing, having fun and turning up, but who were they? And better yet, who was I to insert myself into their reality? I didn't trust them. I couldn't trust them. I liked plenty of them, but not enough to talk to them. And what if they had boyfriends who were jealous, boyfriends down with college and church who would have to face my friends who were gangsters? A conflict between my homeboys and those college kids could have ended badly.

I remember thinking about talking to some of the women just so the trip wouldn't be a total waste, but then changing my mind because what if a woman wanted me to go to a hotel? And what if I follow her to the hotel and she tried to set me up and have some guys rob me and take all my money like some of the women do to horny out-of-towners back home in Baltimore? I spent most of my night checking my money, patting my pocket like it was on fire, making sure my knot was still there. I spent most of my time people-watching the partiers, people-watching others talk, wondering what their conversations were about, and noticing some of the guys I came with having fun, while other guys looked just as paranoid as me. I wasn't in the right headspace to be at Freaknik. I probably should have canceled the trip once DI was arrested.

Wille sat alone on the corner when Des dropped me off after the trip.

“Yo, I want to know everything!” Willie said. “Don’t skip any details!”

“Willie, my boy,” I grinned. “You missed the best trip ever.”

Eventually, I told him the truth, but I had to get a laugh out of the situation.

What's funny is I hate festivals now, probably because I tried to grow up too fast and insert myself in places for adults. What’s not funny is the Hulu documentary taught me that I actually didn't go to Freaknik. Yes, I was at the wild event, but the glory years had passed long before I ever got a chance to attend.