A few months after receiving a diagnosis of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), a neurological disease often triggered by an infection in which serious fatigue leaves many patients unable to work or bedridden, Guy Fincham tried the Wim Hof breathwork technique. He had seen promising signals in a few studies that suggested the technique could influence the nervous and immune systems, and, without a cure available for his condition, he was looking for a way to find relief from his symptoms.

Over time, he explored various forms of breathwork that each played a role in his healing, along with other lifestyle changes like removing processed foods and staying socially connected. Slower practices calmed his mind and body while faster ones like holotropic breathing put his body into a state of hyperventilation and gave him profound psychedelic experiences. Immediately, his ME/CFS relapses became less frequent and he began to feel better. As a researcher, his instincts were to turn to science to get answers about what was causing his experience. However, there was relatively little research on the subject.

“It could have been a lot of belief effect or placebo there,” Fincham told Salon in a video call. But breathwork "gave me a sense of control for the first time over how I felt my body.”

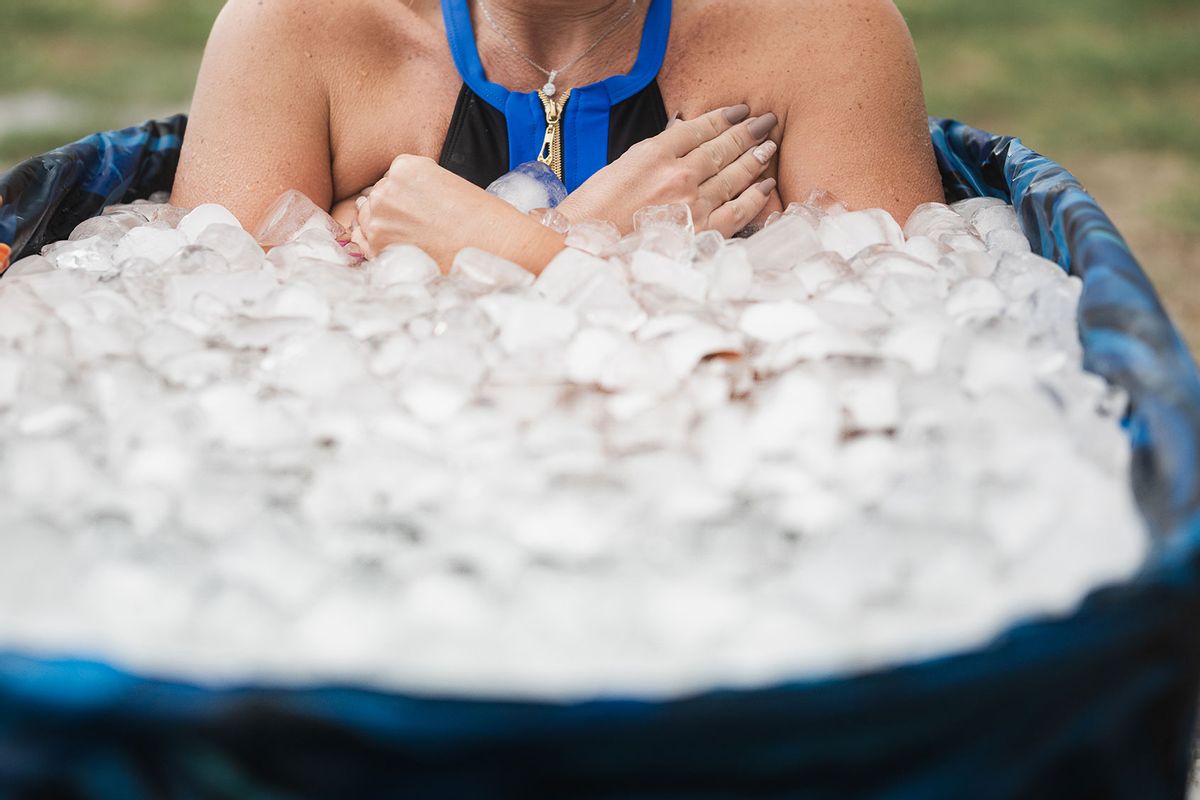

Wim Hof, a Dutch author and motivational speaker nicknamed the “Iceman,” has gathered a cult following for his extreme athletic achievements, including holding Guinness World Records for swimming under ice and running a barefoot half-marathon across snow. The Wim Hof method, which pushes the body to extreme states through regular ice baths, meditation and breathwork, is touted as a way to reduce inflammation and calm the body’s stress response. On Wim Hof's website, his method is described as a way to “become happier, healthier and stronger.”

“Through decades of self-exploration and groundbreaking scientific studies, Wim has created a simple, effective way to stimulate these deep physiological processes and realize our full potential,” it states.

Breathwork techniques, in general, have been shown to impact physiological and mental health, and millions of people use them, with some anecdotally reporting them to be life-changing. Yet relatively little is known biologically about how breathing affects the brain and therefore the body, said Jack Feldman, a neuroscientist at the University of California, Los Angeles who studies breathwork.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

“There are many different breathwork protocols, and there seems to be good data that many of them work and can be very powerful,” Feldman told Salon in a phone interview. “But they're quite different from each other, and I think it will likely turn out that different breathwork practices will have different effects on basic emotional states and clinical problems like anxiety, depression and cognitive function.”

Breathwork is based on practices in pranayama, which basically translates to "controlling the breath" in Sanskrit. The practice of pranayama has appeared in various ancient texts for thousands of years and is connected to yoga, which is derived from the Sanskrit root “Yuj” and roughly translates to joining the breath with the body. Anyone who has taken a yoga class might have done some breathwork exercises, including Kundalini rapid breathing practices like Breath of Fire or box breathing, in which participants inhale and hold, and then exhale and hold the breath for four beats, said Dr. Helen Lavretsky, a psychiatrist at UCLA who studies breathing’s impact on the body in practices like yoga.

"Within the groups that we study, there is a variation where some people do better with some techniques that are not good for others."

In general, faster breathwork practices work by activating the sympathetic nervous system and activating its “fight or flight” mode. In comparison, slower breathing practices work to activate the parasympathetic nervous system and can calm and relax the body, said Tanya GK Bentley, the CEO and co-founder of the Health and Human Performance Foundation (HHPF), a nonprofit that studies the benefits of breathing practices for health and well-being.

Slow breathing practices and those that combine fast and slow breathing techniques, have been shown to reduce stress, especially when performed regularly for at least five minutes at a time and with expert guidance. Slow breathing practices and breath-holds can also build stress resilience by helping the body learn to tolerate carbon dioxide build-ups, Bentley explained.

“These tools can help combat feelings of stress and anxiety that are associated with chronic sympathetic dominance and are common in today’s world,” Bentley told Salon in an email.

However, faster breathing practices, and the slower ones, at times, can trigger anxiety in certain people who have faster baseline breathing rates and are prone to anxiety, Lavretsky explained. There are hundreds of variations of breathwork techniques, with no silver bullet that will work for everyone, she said.

“Western medicine is a kind of average medicine, where we study large groups of people and average out these stats,” Lavretsky told Salon in a phone interview. “But within the groups that we study, there is a variation where some people do better with some techniques that are not good for others.”

Even the trending Wim Hof method isn’t for everyone, including people with coronary heart disease, kidney failure or epilepsy, among other conditions, according to his website. It’s also dangerous to perform the Wim Hof method near water because it can make you feel light-headed or faint. Because of these dangers, Wim Hof’s website explicitly warns against practicing near water in written and video formats. Still, in 2022, one man sued Wim Hof, alleging he was responsible for his daughter’s death because she lost consciousness in the pool after performing his method. The lawsuit is still pending.

(Salon requested an interview with Wim Hof, but his media team only agreed on the terms of a contract that allowed them to abort this story's publication if the story could "potentially damage the talent's image," and fine us 50,000 euros if the terms of the contract were violated. We declined.)

The results of studies evaluating the effectiveness on the Wim Hof method are mixed. In 2011, researchers at the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre in the Netherlands published a study in PNAS indicating Wim Hof could influence his autonomic nervous system and immune response through his meditation practices. These findings were replicated in a 2014 PNAS study with a dozen healthy volunteers who practiced the Wim Hof method.

However, a 2023 study published in Scientific Reports found that 15 days of the Wim Hof method did not affect cardiovascular measures like blood pressure or heart rate. In theory, the hyperventilation breathing technique would trigger the sympathetic nervous system, depriving the body of oxygen and pumping adrenaline that would make blood vessels contract, said study author Sascha Ketelhut, a researcher at the University of Bern.

“The question is, what is the long-term effect?” Ketelhut told Salon in a video call. “The research, in my eyes, isn’t there yet, at least for the [cardiovascular] parameters we assessed.”

The technique does seem to increase epinephrine, causing an increase in a substance in the body called interleukin-10, which can reduce inflammation, said Omar Almahayni, of the University of Warwick in the U.K. In a review paper Almahayni published last month in PLOS One, studies did show the Wim Hof Method to help with inflammation.

We need your help to stay independent

“However, given that all studies included in our systematic review exhibit ‘high concern’ for risk bias, it is important to acknowledge that the Wim Hof Method is still in its early stages of investigation, with limited trials conducted thus far,” Almahayni told Salon in an email. “As a non-pharmaceutical treatment, Wim Hof Method can probably be used within lifestyle medicine to decrease inflammation in people suffering from inflammatory disorders, [but] further research is needed to validate its effectiveness and safety for broader recommendations.”

Yet there are some important limitations to studying breathwork in humans. In 1991, Feldman published the results of a study in mice that found the source of the rodent’s breathing rhythm was a part of the brain called the pre-Bötzinger Complex in the brainstem. But this region in humans is difficult to image because of its location, and, for obvious reasons, it can’t be removed and put under a microscope. His research in mice has indicated that certain slow breathing techniques can calm the nervous system, which suggests a real effect since mice cannot be subject to placebo effects like humans.

Many studies in this field among humans are not conducted with enough statistical power and scientific controls to be considered strong evidence, but some promising results have arisen, Feldman said.

In one review of 15 studies published last year in Frontiers of Human Neuroscience, breathwork techniques that slowed breathing to fewer than 10 breaths per minute were shown to slow regions of the brain associated with thought processing, memory and emotion, along with heart rate. Participants, in turn, felt more relaxed and present while also reporting less anxiety, anger and depression.

Year after year, the prevalence of these conditions is increasing. And with the cost of healthcare in the U.S. higher than anywhere else in the world, people are looking for ways to take their healing into their own hands. Evolutionarily, triggering the sympathetic nervous system or “fight or flight” response was helpful for survival when human beings were threatened by wild animals or needed to make a run for it. But for many, the sympathetic nervous system is out of balance with the parasympathetic nervous system, which, along with the vagus nerve, works to calm the body.

“We’re kind of exhausting ourselves as humanity, and we are constantly bombarded with negative events like climate change, wars and local disasters,” Lavretsky said. “We don’t give ourselves the ability and space to recover, and all of these breathing practices really help to rebalance the system.”

A breath can create distance from negative events that cause toxic stress and unhealthy reactions in the body. Breathwork research, although in its infancy, seems to suggest that something about a breath can at least in part create enough space for the body to enter a state of rest and recovery, Fincham said.

“The more we part and separate from nature, the more we need to be drawn back to these practices in order to heal from industrial diseases,” Fincham said.

Shares