It took Melissa G. Moore a decade to convince Dominique, Denise and Tanya Brown — sisters to Nicole Brown Simpson, the ex-wife of former all-star NFL runningback and actor, O.J. Simpson — to make a documentary about their sister. Now, on the 30th anniversary of the day Nicole and her friend Ron Goldman were brutally murdered in 1994 outside Nicole's townhome in Brentwood, Calif., Moore says the sisters are "in the right space to actually tell the story."

Lifetime's "The Life and Murder of Nicole Brown Simpson," which airs in two parts on June 1 and 2, chronicles the tragic double homicide and the resulting media frenzy. However, and perhaps more importantly, the documentary shares Nicole's story, the "one key side" to the infamous crime and subsequent highly publicized trial that has "always been missing," per a press release from Lifetime.

Though O.J. Simpson was acquitted of the murders in 1995 and maintained innocence until his recent death from metastatic cancer in April, in 1997, he was found liable for both deaths in a civil lawsuit filed by the victims' families. The ex-athlete was ordered to pay $33.5 million in damages.

While many filmmakers and journalists have endeavored to rehash the hugely sensationalized case, Moore's documentary stands out as particularly unique, not only for its focus on detailing Nicole's life but also for Moore's personal connection to the true crime genre.

"The sisters were in a space to actually tell the story — enough time had passed."

Moore's father, Keith Hunter Jesperson, was a serial killer who assaulted and murdered at least eight women in the early 1990s. Known as the Happy Face Killer, Jesperson often drew smiley faces to confession letters he submitted to police and various media outlets. This experience profoundly shaped the trajectory of Moore's career as a true crime filmmaker and podcaster. For a time, it also stymied her ability to move on with her life without feeling sullied by, and inextricably connected to, her father's actions. In 2009, Moore published "Shattered Silence: The Untold Story of a Serial Killer's Daughter," a memoir that detailed her journey toward healing and self-love.

Now, with her latest project, she hopes viewers will come to see the depths of Nicole Brown Simpson's strength.

"She was a fighter," Moore said. "That's what I think people will be surprised about — the whole time she was fighting for her life."

Check out the full interview with Moore, in which she discusses Nicole as the documentary's North Star, the isolating experience of domestic abuse, and the idiosyncratic relationship she has with true crime stories.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What does it mean for this project to be released so close to O.J.'s death?

We kind of planned it, but it didn't change anything at that point. We were done filming months ago, and we were in the final stages of editing the last hour of the documentary. One of our North Stars in this documentary was every act started and ended with Nicole. And so it didn't change anything in the sense that we were still going to end this documentary on Nicole and it wouldn't feel right to tell her story and then end it with his death — that would be a contradiction of our intention in all ways. So, we were just at the point where we were getting ready to submit, for legal reasons, all of the statements for O.J. to make a rebuttal or to comment. He passed away before that could happen.

This documentary notably features 50 participants, which is quite a lot. You have everyone from journalists to former LAPD to jury members. What was your process in reaching out to so many participants?

So starting out, the genesis of this whole documentary started 10 years ago on the 20th anniversary of Nicole's passing. Denise [Brown] and I had a connection because I'm a survivor of domestic violence, and she was a speaker. So I was raising funds for shelters as well — that's how Denise and I met. I would tell her, "Hey, we have to do something about Nicole. What about now on the 20th [anniversary of Nicole's murder]?"

She's like, "No, it's not time yet."

On the 25th — "How about now?"

"No."

And then as it approached 30 years and on Jan. 1 — it was New Year's Day, 2023 — she said, "All right, it's time. It's the 30-year anniversary. Let me talk to my sisters and see if we could make this happen." And so it was just the right timing to tell her story. Everything about it felt right, the sisters were in a space to actually tell the story — enough time had passed. And so they were the genesis. They were the start.

I asked them what was important to them, and they're like, "Well, we want people who've never spoken before to come forward." I'm like, "Yes, that's what I want too."

So they did a lot of the initial outreach to the people that were closest to Nicole. And then from there, we progressed on their outreach . . . But some of the LAPD that you see in this documentary, we made outreach not knowing what stories they were keeping. And when they sat down and did the interview, we were just gobsmacked. Like, wow, "You witnessed Marguerite's [O.J.'s first wife] domestic violence and Nicole's." So there's a lot of times that we were sitting in front of somebody interviewing them and were just surprised that none of this was ever known.

Dominique Brown, Tanya Brown and Denise Brown. The Life and Murder of Nicole Brown Simpson. (Lifetime)What were the biggest challenges in making "The Life and Murder of Nicole Brown Simpson"?

Dominique Brown, Tanya Brown and Denise Brown. The Life and Murder of Nicole Brown Simpson. (Lifetime)What were the biggest challenges in making "The Life and Murder of Nicole Brown Simpson"?

The biggest factor was just giving enough time to each participant. And just that balancing act. I mean, there are so many stories, just happy memories of Nicole that while we would love to share them, we couldn't.

There's a story that Denise shared about her sister [Nicole] loving this horse named Diablo that kicked her off. And her mom had this intuition that something was wrong with her daughter. And it was foreshadowing, basically, what happened the night Nicole was murdered. Her mother [Judith] "Dita" had this feeling that something was wrong with her daughter. Nicole was young — I think she was 13 years old when she was kicked off Diablo and was put in a coma or she was in critical condition. She had a scar on her forehead from that fall off the horse. But just how her mom had this feeling that something was wrong with Nicole and went to the stables and found her daughter unconscious on the ground. So while that was a really impactful story, it's just like, now we have to wait for the other stories and give enough time to each storyteller to share their memory of Nicole.

Did you ever consider including Nicole's kids Sydney and Justin Simpson in this project?

Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. Yeah, I met with them in 2016 and wanted to have them. A part of this was really about timing. One thing that people aren't aware of is that they started their own families. They were really young, new parents when we started making this documentary. And then their father passed away at the end of this documentary. So hopefully, my goal is that there will be a time when they feel ready to tell their story and it works for them. But unfortunately, the timing of this didn't work out for them.

Some of the most heartbreaking scenes as a viewer were those moments when the Brown sisters and Nicole's friends described learning of Nicole's murder and the subsequent wake and funeral. Denise has this moment where she talks about purchasing a dress for Nicole's wake and funeral and having to ensure that it had a turtleneck because of how badly her neck had been cut. Is that something she was open about sharing with you at first? And did you allow the sisters to have time together to prepare for what I can only imagine was a hugely emotional process of sharing all of these really intense memories?

Yeah, while we interviewed them for hours, there were so many, countless hours of conversations over the years to get to that point where they could openly share these details. There were so many conversations. I mean, countless hours of conversations leading to even picking up the camera. And then there were days of filming with them when we did have the camera. So we just let them freely speak and share their stories.

And how did you decide how much pain to actually show without being exploitative?

That's a really good question. I don't feel like I censored their pain at all. I felt like that was the pathway through it — just to let them unleash their pain in real time. And let them share it and expose it because that's what it is. There is something vulnerable about that. There's something real about that. And so there was nothing that I felt like was left on the cutting floor about what their grief was.

It certainly came through as a viewer. Much of the documentary was extremely heavy and harrowing, but seeing Nicole's sisters and family and friends recount how they felt in those moments only gave you the tiniest glimpse into what it could have been like. And even that was incredibly difficult to go through as a viewer.

I feel like one of the gifts about this documentary is that not only do you get to know Nicole — you get to know her sisters, you get to know their family, the Brown family. And to get to know the Brown family is to love them. And that makes it even more heart-wrenching when you find out what happens to them as a family. I feel like this documentary also highlights just what a wonderful family they were. And then they go through this horrific [situation] and it just makes it even sadder, I think.

One thing I was really curious about was the inclusion of Polaroids of Nicole looking extremely battered. It was interesting to see how those photos were animated, almost like a live photo on an iPhone. Can you talk about why you chose to do that?

"When you're a crime survivor, you lost control."

Well, because you see those images so stale — they didn't they don't show her life. And I feel like that was the whole purpose of who Nicole is. I think Denise said it best to me, and I don't know if she said on camera, but I'll never forget. She said, "Oh, my gosh, she's walking." When she saw the video of Nicole, it was like she was brought back to life. I felt like it was a really important factor — to bring Nicole back to life so that people could get to know her and hear her voice because if you close your eyes, you could probably picture or hear O.J.'s voice. He has this distinct voice. How do we not know what Nicole sounds like? And so to take her from two-dimensional to three-dimensional was always a goal. And thankfully, we have technology to do that, with her blinking. It really makes you feel something.

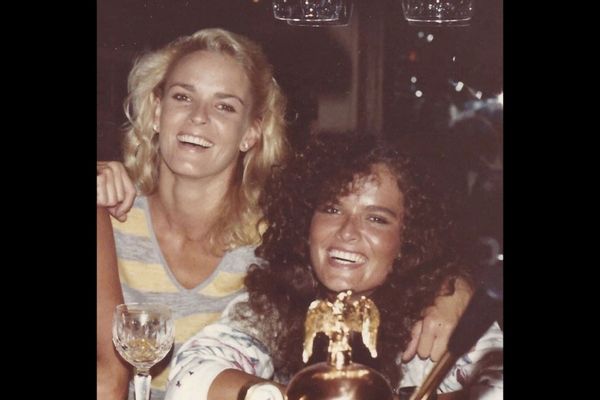

Nicole Brown Simpson and Denise Brown. The Life and Murder of Nicole Brown Simpson. (The Brown Family)You just briefly touched on hearing Nicole's voice. I was going to talk about how we see lots of home video footage in the docuseries. We hear her voice. We see her as a child blowing out birthday candles, and riding on her bike. It was all extremely emotionally visceral. Were the Brown sisters very forthcoming with that content?

Nicole Brown Simpson and Denise Brown. The Life and Murder of Nicole Brown Simpson. (The Brown Family)You just briefly touched on hearing Nicole's voice. I was going to talk about how we see lots of home video footage in the docuseries. We hear her voice. We see her as a child blowing out birthday candles, and riding on her bike. It was all extremely emotionally visceral. Were the Brown sisters very forthcoming with that content?

Yeah, that was one of the key parts of doing this documentary. It was like, "OK, so we're going to tell them a cool story. All right. But we need the materials to do it. We need videos."

The Browns were actually nervous that they didn't have enough. I pulled up to Orange County and they open up the garage door and there's tons of bins of home videos and photos. I was like, "Oh, there's plenty here. There's so much." But then there was the task of, "How do we digitize these very old, old reels?" I mean, they're fragile. They're brittle. They could break if you roll them. So while trying to preserve them, you could damage them. So that was an art in itself.

There is also a backstory that Denise told me about how some of that very early footage of Nicole when they were little babies was at the bottom of the ocean at one point in a container. When they [the Brown family] left Germany, their belongings were shipped in a container. And one of the containers fell into the ocean. They later revived it, like brought it back up. But that was also interesting to note that some of the footage could have been lost forever. But we get to see it because it was restored and brought back to the surface.

Why is it so important that we hear Nicole's voice and see her at different stages of her life?

So I let my curiosity about who she was as a person be the guide, and that was, "How do I get to know somebody who's no longer here and really understand what her personality, her spirit was like?" And the one way to really do that is to watch videos, to hear the stories from people. I mean, you're a stranger to me. If I wanted to know you, I would talk to your best friends, you know?

What I love too is that she was in her 30s, and so she had many layers of friends just like we all do. And so to tell the story of Nicole, you'd have to tell all of her generations of friends. So if I talk to your friends from high school, they would tell me a different story than your friends today.

And we do see that. We see Nicole's close friend Robin [Greer], and we see Kris Jenner. I love the photo of Nicole and her Ferrari that had the "L84AD8" ["late for a date"] license plate. And especially when she's in that era when she meets Ron and just is so happy. Of course, that comes shortly before the end.

Yeah. I love that. Dominique said that she's happy she got to see her sister have a good life before she was murdered, because her life was so hard and hellish before that with O.J., with the abuse. And so that gave some solace to Dominique. And I'm glad that she got to hear those stories from friends.

The sisters weren't producers in this at all. So while they did outreach, they didn't see any of the edits until the very end, when we had them sit and watch the four hours to see what they thought about it. And sitting there and watching them watch this for the first time — they were learning things that they never knew about before. They didn't know about Marguerite's abuse. They didn't know about the details from Robin, about the stories that Nicole was telling. In the series, she tells Robin that the kids broke the door, and then she's telling other people different ideas of what happened on Gretna Green [Way] that October night. So a lot of it was new to them. And it was the first time that all three sisters listened to the 911 call in its entirety.

What were their reactions to that call and everything else that they hadn't previously known about?

I think anger. Watching it, they just got angrier and angrier, because they knew. They knew, but then to see it in full conflict, to see everything in full picture — all the pieces were now whole. And that was only possible because of friends coming together to share their little fragments of their stories, and then it made a whole picture for them. I mean, a lot of the abuse was hidden from the sisters and from close family friends. And that was to protect them. Nicole was protecting people close to her. And that's what I hope that people actually get from this documentary: how lonely Nicole must have been, and how lonely and isolating it is to be a victim of domestic abuse because you can't really share with people that you love what's going on behind closed doors. Because they're going to tell you to leave, of course. And then they're not going to understand why you're staying. So you have to justify your actions to people you love.

In speaking about the intense media frenzy that followed Nicole's murder and O.J.'s trial, Dominique actually shared this really heavy anecdote about how she used to make this game out of being chased by the media helicopters basically to protect Sydney and Justin.

They'd be at the beach, and they would grab their towels and pretend to be superheroes, running down the beach. But it was a result of the fact that they had no privacy at that time and that they were being followed, under constant media surveillance. I was quite affected by that. I think the fact that these are little kids who no longer have a mother, and their family who's also in the process of grieving is now just trying to maintain a sense of normalcy for them. Why did you choose to include how the sensationalization of the case affected the Brown family and Sydney and Justin specifically?

"Every case that I work on, I have full consent of everybody working with it. Because to me, it is a consensual project."

Because that added another level of victimization to them. Because it was so sensational, there was a voyeuristic greed to it. And it came at every expense. There were no boundaries. And it was limitless, the access that they wanted, without consent. So these children have no rights, and the family circled them and protected them. But everybody wanted a piece because everything led to money. So if they got a scoop, it meant more money. When doing the research for this, there was a friend of Nicole's whose housekeeper stole one of the photos while cleaning the house and sold it to the tabloids. Everything was money. And so there was a level of greed that I think was important to show. I think it was an "Inside Edition" reporter who said that it became a business opportunity.

I also wanted to discuss your background. You've spoken extensively about your being a crime survivor, as well as your father's past. I'm curious to learn if you ever feel emotionally fatigued by being immersed in true crime work, especially given your background of having lived through it. I know I have a hard time watching too much true crime at once, and I certainly don't have as much of a close tie to it as you do.

I think it's one of the best questions I've ever been asked. I totally do. Thank you for asking that. There's a couple stories that will completely get me fatigued. Let me see how I can answer that, because I've never been asked that. I have a memory of when I was first working in true crime, and I met with Shasta Groene. Are you familiar with her case?

Yeah, I am.

Okay. That was a local case. And I sat down with her to do her interview. And as a crime survivor, she told her story uncensored. There are some horrors that this girl endured that were so shocking, and so horrific, that they stayed with me even to this day. I can't even repeat some of the things she told me. And I felt that she told me that because she knew I could hear it. But it doesn't make it easy to hear. And it haunts me to this day. I've just never been asked this. I'm trying to figure out how to answer it.

I feel like I go around in my life, and I have an association with a crime story. Like, everything. Some things I feel like I can share and some things I can't. I'll keep it as a thought to myself. So for example, if I'm driving and I see a tan beetle, a VW [Volkswagen] bug, I'll think of the Ted Bundy survivor. Other people will be saying "Slug bug!" [makes punching motion] and I'll be thinking of a Ted Bundy survivor. Or when somebody describes something, I'll have a flashback of another crime case. So I feel like I have a box of stories in my head for me to know.

That's incredibly interesting, and I kind of resonate in a completely different way. My mom is a 9/11 survivor, and I published something last September — it was a personal essay about how this intergenerational trauma has affected me, even though I wasn't even there. I was alive, obviously, but even now I'm getting an emotional reaction in my chest. And it is so interesting to think about the ways that things that either people in our family did or went through can have that really specific and lasting impact on us that maybe no one else, or maybe more people than we realize, relate to — as I learned when I wrote my own story. An experience can feel very isolating because it is so specific, especially in your case, which I can only begin to imagine.

And you don't want to inflict trauma on someone by telling them a story that they're not prepared to hear or have to live with because you know how it affects you — what you heard or what you witnessed. So it feels like it has to live in a capsule within you because to release it is to pass down something that shouldn't. You don't want to have that effect on a child or somebody that you love or your friend, you know.

Nicole Brown Simpson, Dominique Brown, Denise Brown, Juditha Brown, Louis Brown and Tanya Brown. The Life and Murder of Nicole Brown Simpson. (The Brown Family)Thank you for sharing that. That was an extremely powerful sentiment. My next question is sort of related. What do you feel that true crime storytellers should be focusing on? And where can true crime really improve? What is the genre missing right now, and how would you like to see it evolve?

Nicole Brown Simpson, Dominique Brown, Denise Brown, Juditha Brown, Louis Brown and Tanya Brown. The Life and Murder of Nicole Brown Simpson. (The Brown Family)Thank you for sharing that. That was an extremely powerful sentiment. My next question is sort of related. What do you feel that true crime storytellers should be focusing on? And where can true crime really improve? What is the genre missing right now, and how would you like to see it evolve?

I actually feel like true crime is going in the right direction. It felt like it was off course for a beat there. It was really focused and still tabloidy, and now I feel like with documentaries like "Quiet On Set" or these high-end, quality caliber documentaries are showing that people have an appetite for actually hearing survivors tell their story. And not just for a voyeuristic sense, but to really understand a survivor's experience. So I feel like true crime is going in the right direction. Whereas before it was really like — I don't want to like name names of shows — but it's just like fast food, you know? It was really poorly executed. And it was just about all the salacious details and none of the substance.

Right. And I think a lot of what I feel like I've seen of true crime in the past has been focused not on the victims and their families, but on the perpetrator of alleged crimes. And I think that can be a sticky territory to navigate as well, especially when we hear stories about victims' families not being notified about the production of a documentary, and we're talking about potentially re-traumatizing people all over again.

Well, one thing that I noticed about this, and being a crime survivor myself, is that when you're a crime survivor, you lost control. You had no control. If you're a rape survivor, things were taken from you. Either your voice was taken from you, your body, your story. And so I feel like what's important about honoring survivors is not to steal their story. So in every case that I work on, I have full consent of everybody working with it. Because to me, it is a consensual project. I would never feel good about myself making a work and exploiting someone's survivor story without their consent. That's just not how I operate. Whereas some productions do that. And then they're the last to be notified. But that to me is revictimizing the survivor because they didn't have control over the crime. And then now they don't have control over their own story.

This docuseries was made in collaboration with the National Domestic Violence Hotline. What do you hope people, specifically people who may find themselves in abusive relationships — especially in light of recent media developments — take away from this project?

Well, I hope they feel seen, because it is isolating to be a survivor of domestic violence. I hope they feel like they understand that they're not alone in their experience and that there are other people that have endured that. Unfortunately, it's such an epidemic — violence against women and domestic violence in general — but especially violence against women, that the likelihood that a viewer or somebody watching this knows somebody that is being abused [is high.] So I hope that they'll see how isolated the victim feels.

What do you hope that people come away with about Nicole after they've watched "The Life and Murder of Nicole Brown Simpson"?

She was a fighter. She was a fighter. That's what I think people will be surprised about — the whole time she was fighting for her life.

"The Life and Murder of Nicole Brown Simpson" airs at 8 p.m. ET on June 1 and 2 on Lifetime.

Shares