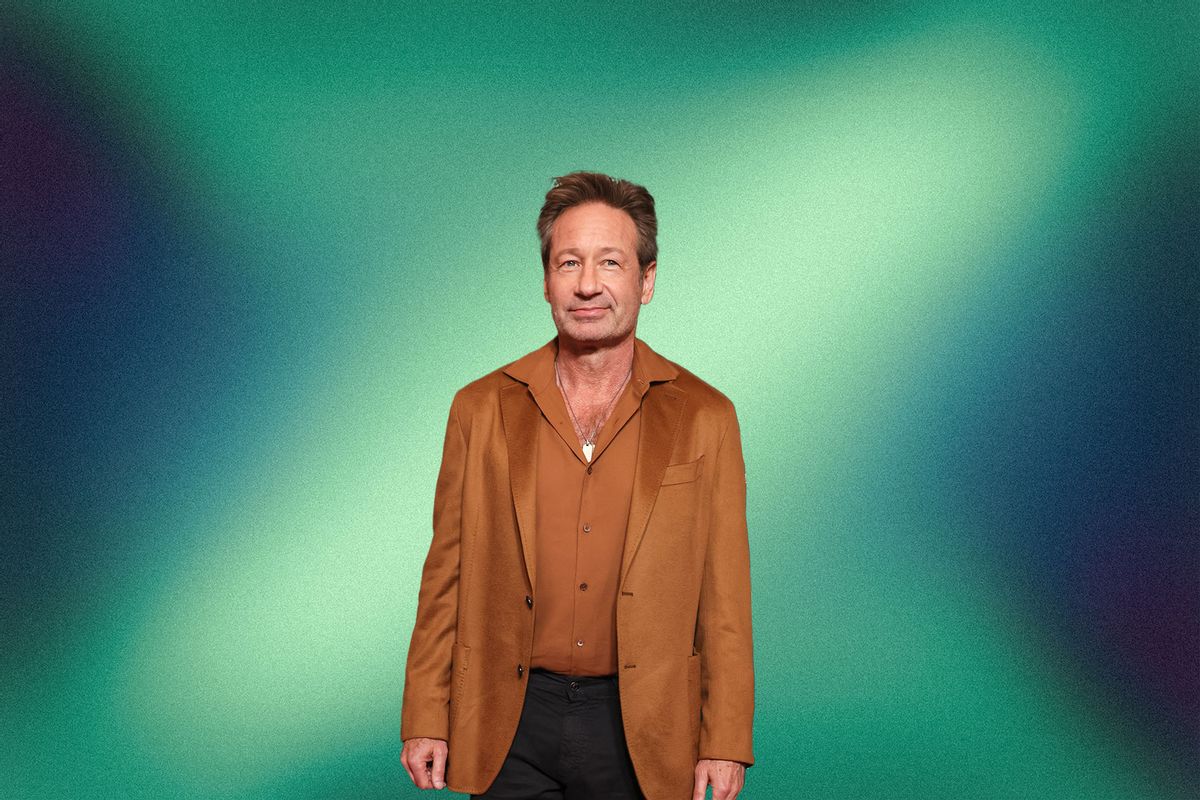

“It's all failure to me,” says David Duchovny. The Golden Globe-winning actor has led the kind of life most people would regard as a home run — a Masters degree from Yale, a string of iconic television roles on series including “Twin Peaks,” “Californication” and “The X-Files,” a lengthy and creative resume as an author, director, producer, podcaster and musician. Yet from his podcast “Fail Better” to the new movie he wrote, directed, co-produced and stars in (based on his novel “Bucky F*cking Dent”) there’s something about losing that he’s drawn to. And what more fitting metaphor for it than the famed 86 year-long “curse” of Boston Red Sox?

In “Reverse the Curse,” (now streaming on Amazon Prime, YouTube and other platforms) Duchovny plays Marty, a terminally ill Sox fan trying to make peace with his adult son Ted (Logan Marshall-Green) with the help of a “death specialist” nurse (Stephanie Beatriz) over the course of one of the team’s most memorable seasons. During a recent “Salon Talks” conversation, Duchovny opened up about his “instinctual distaste for win at all costs mentality”— including Trump’s — the eternal appeal of “X-Files“ and why a man who has graced the cover of GQ wrote himself a nude scene that “I think we can laugh at."

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This takes place in 1978, an historic year in baseball, and baseball forms the backdrop of this father-son story. Tell me about the curse.

The literal curse in the movie is the curse of the Babe, which is when Red Sox owner Harry Frazee sold the rights to Babe Ruth to finance a Broadway play. He sold Ruth to the Yankees, and the Sox never won again. They hadn't won in 1978, when this movie takes place, when the book takes place. That's the curse of the Babe that needs to be reversed.

More metaphorically, it's a curse between a father and a son, and reversing the curse in their life. One of the things I talk about in the book and in the movie is how we tell the stories of our lives. I know it's become popular in therapy recently, seizing the narrative of your life and recasting it in a certain way that's healthier, or more loving, or more fair in whatever way. Instead of being a victim, you're something else. Instead of being a hero, you're something else. That's really the reversal of the curse. Aside from the baseball backdrop is this curse between fathers and sons that I'm dealing with in the film.

I love seeing a story that is about how we parent adults. Our kids don't fly out of the nest the moment they turn 18 and then stop being our children and our responsibility. But what happens is the dynamics when you're both adults change, and this is a story that is very much about that, and the reversal is also caretaking.

The son in the movie and the story starts to treat the father like a child in a way, because he's taming the world. He's lying about the world, because in the story, the father's health deteriorates every time the Red Sox lose. So the son takes it upon himself to fake certain outcomes and to keep that truth from his father. That's something you would normally associate with a parent for a child, to keep them in a bubble until they can handle the truth of what can happen in the world, or failure or disappointment or heartache.

It's his version of Santa Claus.

He's like the baseball Santa Claus.

Speaking of reversals, I heard that this movie started as a movie, and then became the novel, and then reimagined itself again as a film. What happened? This seems like a long journey, because you originally saw yourself as the son.

"It wasn't like people were knocking down my door and saying, 'Direct this film, because you have a magic touch.'"

Yeah, I did. I wrote the screenplay. And the first movie I did, didn't do great business. [2004's “House of D”] It wasn't like people were knocking down my door and saying, “Direct this film, because you have a magic touch.” I liked the film that I did, the first one. But it wasn't, quote, unquote, a box office success or anything like that.

Once that happened, I had the script and I wanted to make it, and I couldn't make it. Then I got busy doing other things, mostly as an actor. Then five, six, 10 years later, I was raising my kids here in New York, and they were at school. They were now in middle school, high school. I had a lot of time during the day and I was like, s**t, I like the story. I want to get the story out there. I'm going to write it as a novel because I can control that. I can get that out. That’s how that happened. And then I was like, oh, that's a great story, I want to rewrite the script. I did that and tried to get it done, still with me as the son. It would have been terrible if I'd been able to get the money together with me in my mid-50s, trying to play early 30s. Luckily, it got postponed long enough that I could play the dad.

I saw an interview you did about the book, where you said that this is a story about losers, and about loving the losers. That's a recurring theme in your in your work in the last few years. You have a podcast called “Fail Better.” What is it about that side of of life, and the experiences that we all have, that you're so driven to talk about?

I just think it’s an instinctual distaste for win at all costs mentality. You point to somebody like Trump, who can't accept the loss of the election and the hysteria that's put the nation into when you have his backers who are also refusing to accept a loss. With Trump, it seems like a matter of life and death, not ever to lose.

Even before that, George Steinbrenner turned the Yankees into a winner, but it was all about winner, winner, all this winner stuff. I played sports my whole life, and I like to win, I love to win. I was very competitive. But I loved the game more, and it was more about fair game, and hugging it out afterwards, hugging the person that beat you, and giving them respect. So I have been kind of horrified, even like in athletics, seeing people say, “Losing is not an option.” I'm like, you think so? Let's see.

I wanted to get at the heart of what I see as a sickness, literally. What's at the heart of that possibly humiliation or shame around the concept of losing, being beaten, coming in second, all this “America first” s**t that I just hate? I wanted to try to heal it. I wanted to try to open up a discussion around that. With a book and a movie like “Reverse the Curse,” I'm going at it very obliquely as an artist. The podcast is more going at it head on. I'm like, what's the problem with us?

And it's warping our kids, because we're raising kids in a bubble where the idea of being less than perfect and less than No. 1 is unacceptable to parents.

I feel the winning mentality is also a reaction against that “Everybody gets a trophy” mentality, which I am also not a fan of. Life does have winners and losers, but it all changes. You take the loss, and that doesn't define you. So, on the one hand, you've got “Everybody gets a trophy.” On the other hand, you've got “Only winners count.” And I'm like, there's another way.

This movie is also very much an exploration of our terror of the idea of “losing” to disease or “losing” to age. Aging or sickness or death are seen as defeats in American culture. You are aged in this movie, you are sick in this movie. You don't look good. There’s a scene where you are nude, and you're talking about what it looks like to have an aging body. Tell me about that, and why that scene is so important.

"You can look at horrific things with a sense of humor."

You can turn it into humor. You can look at horrific things with a sense of humor, and the humor comes from the fact that it's going to happen to all of us. It’s not like some people age and some people don't, some people die and some people don't. If I've got one of my main characters — me — showing his his naked body to his son and saying, “It looks like a dead sparrow where my c**k should be,” I find that funny. I think we can laugh at that, and then hug it out. And he comments on his son's penis in a way that's funny. I'm laughing and I'm also moved in a way.

You cast this movie with funny people. This is a funny movie.

I think funny actors can do anything. Dramatic actors, I don't know if they can do funny or not. Sometimes they can and sometimes they can't. That's why I cast Stephanie Beatriz. I saw her on “Brooklyn Nine-Nine.” She brought so much depth to that. I just watched the movie again yesterday, I hadn't seen it for probably a year. And I was really struck by her performance more than anything. She's so deep and has such easy access to real pain, and in a facile way can show it. I'm just grateful that she did that in my movie.

You've twice now returned to roles that you originally created 30 years ago. You did it on “Twin Peaks” with Denise, and of course, “X-Files.” I want to ask what it is like. Were you wondering what Denise had been up to and what Fox has been up to when you were presented with, “Here’s where these characters have gone”? You're a writer, you must be thinking about these their their storylines and their arcs.

I separate my my sense of myself as a writer from my job as an actor, unless I'm being enlisted. On “The X-Files,” I did write episodes, but I'm not enlisted as a writer in the room. That's not my job, I leave that to the experts in that I might have opinions or whatever. I'm not going to tell David Lynch, “Hey, I want to rewrite you.” I don't even have that door open in my mind.

"How is Mulder 30 years later? I find that to be an interesting question."

But to answer your question, yes, that's exactly how I think of it. It’ll be interesting to visit this person 30 years later. That's an acting trick. You can't play it the same way. It's not the same reality, not just the outside world, but the person. Thirty years is a long time. A lot has happened. Your character maybe doesn't change, but other things do change. So how do you play that? It's subtle. It’s a pivot. You can't play a new character, because you don't want to break that bond with the audience. You can’t all of a sudden show up with a French accent because you want to work on your French accent for Mulder. But how is Mulder 30 years later? I find that to be an interesting kind of a question. Same with Denise.

These two shows were adored, were monoculture phenomenons back in the day when we didn't have 100,000 other things competing for our attention. Now we do have 100,000 other things competing for attention and they are still such a huge part of my generation, but also our kids' generations. What do you think it is about those two series that is so indelible and enduring?

In the case of “Twin Peaks,” you have just a really singular artist behind it all with a vision that is unique. You can you can probably watch a minute of film and you’d go, “That's got to be David Lynch.” There’s not many people you could say that about. You could maybe say that about Paul Thomas Anderson or Scorsese maybe or Tarantino, but Lynch even moreso because he's such an odd and singular imagination.

I think that just endures. One has a taste for it or one doesn't. But he's never bent in any way to try to be popular or anything. It always seems to be coming directly from his unconscious in many ways, and who does that? He does that, I think only.

With “X-Files,” I think Chris Carter just came up with an amazing frame, an amazing precedent of a show that could just spark off in so many different directions and spoke to a sense of wonder but also a sense of foreboding. I can't think of another show that has as much hope and fear in it. That'll always be a powerful mixture.

And humor.

Well, we tried. That was something that grew. There was definitely an irreverence to the Mulder character from the beginning, and something that I was really interested in growing as we went along. We were lucky enough to have great, great writers who could also write comedy like Glen Morgan and James Wong, but also Vince Gilligan, who went on to do “Breaking Bad,” of course. Darin Morgan, Glen's brother, who's a very unique writer that people don't really know about. He wrote probably only eight episodes, but they're usually in the Top 20 of what people love about the show. [Darin’s credits includes the classics "Jose Chung's From Outer Space,” "Clyde Bruckman's Final Repose"and “Humbug.”]

In the midst of all of these other things that you're doing, you're going to be playing in London this summer. You are also a musician. I want to ask how the music fits into everything else that you're doing, and how your different creative projects kind of feed on each other.

The music is different, because it wasn't something that I ever thought of. It was really picking up a guitar more than 10 years ago now and just trying to amuse myself, and then kind of finding that I could string chords together and maybe hear melodies. And I knew I could write words, so that just became an avenue that was opened to me that I didn't ever think about. What's interesting to me about that whole process was, even as I am older, I wasn't an old songwriter. If I wrote my first song when I was 53, in my mind, I was 17. Not lyrically, but the parts of my brain that were engaged were super new. It taught me something about life in a way, that it's about that mindset. They call it Zen mind, beginner's mind. On the one hand, we have Malcom Gladwell saying you’ve got to do a million hours. On the other hand, you’ve got Zen mind, beginner's mind. I'm both. I put in my hours as an actor, I got to a certain, I don't want to say mastery, but a certain kind of comfort in that area. Then all of a sudden, I had another avenue where I was completely in the dark and young, and it informed everything.

Another opportunity to fail better as a beginner.

It's all failure to me, because I'm just never going to be that good. You know, I'm never going to be a great player, because I started too late. I'm never going to be a great singer, because I just don't have the natural gift. But I'm still in there. And I'm trying to do something. I find that that failure, the failure of being able to do it great, can also make great music. Perfect music doesn't exist. So stumbling blindly in the dark, trying to make good songs, has a certain kind of energy that can work sometimes.

Read more

Salon Talks with actors from your favorite series

Shares