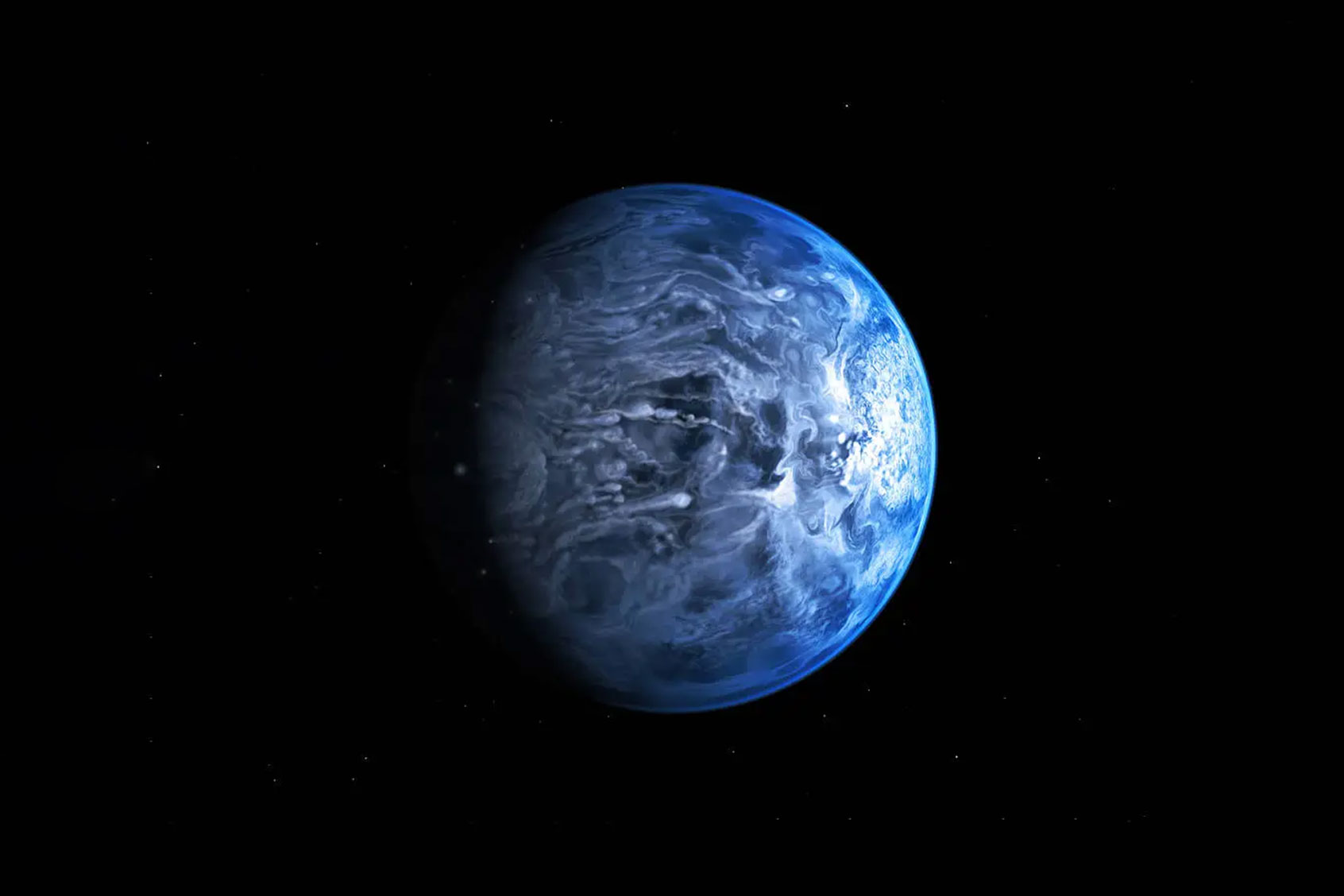

Scientists have discovered thousands of exoplanets in other solar systems and some of them are especially weird compared to our stellar neighborhood. For example, HD 189733 b, a planet 65 light years from Earth in the constellation Vulpecula, is larger than Jupiter, the largest planet in Earth's solar system. But it also rains molten glass at extremely hot temperatures, with the scorching shards flying sideways due to winds that reach speeds of up to 5,000 mph (8,046 kph).

Although it was discovered in 2005, immediately drawing attention for its distinct blue-and-white appearance, HD 189733b is still revealing strange properties to us. A recent report by the James Webb Space Telescope revealed that the exoplanet probably smells like rotten eggs. Apparently the explanation can be found in hydrogen sulfide, the same compound found in crude petroleum, sewage sludge and volcanic gases. Hydrogen sulfide infamously smells like flatulence or rotten eggs, a fact not lost upon the astronomers who discovered it in the atmosphere of HD 189733 b.

"Hydrogen sulfide is a major molecule that we didn't know was there. We predicted it would be, and we know it's in Jupiter, but we hadn't really detected it outside the solar system," Johns Hopkins University astrophysicist and team leader Guangwei Fu said in a statement. "We're not looking for life on this planet because it's way too hot, but finding hydrogen sulfide is a stepping stone for finding this molecule on other planets and gaining more understanding of how different types of planets form."

Fu added, "Sulfur is a vital element for building more complex molecules, and — like carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and phosphate — scientists need to study it more to fully understand how planets are made and what they're made of."