Talk about outlandish — I’m here at the edge of the world to learn more about the demise of ancient giant sloths, as well as environmental and wildlife conservation lessons for the future. In the quirky and offbeat city of Punta Arenas, located in southern Chile, I duck inside a local ethnographic museum where I take in the ghoulish remains of Milodón darwinii (Darwin’s sloth, or Mylodon), including claws, skin and fur.

Strolling further, I notice a model of HMS Beagle, the ship which Charles Darwin sailed on from 1832 to 1835 throughout South America. During his voyage, Darwin uncovered the remains of four species of giant sloths, three of which were new to science, and such discoveries would later help to inform the naturalist’s theory of evolution. Indeed, after observing the relationship between extinct giant sloths and living species, Darwin developed his “law of succession of types;” that is to say, the relationship between past and present inhabitants of a given region.

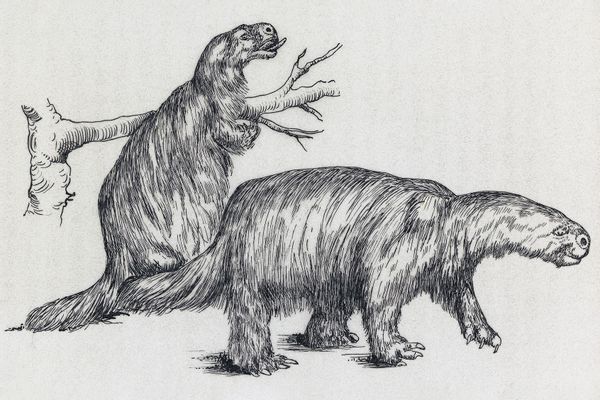

Mylodon, which lived between 1.8 million and 12,000 years ago, was mainly vegetarian but was also an opportunistic omnivore. The creature is related to current armadillos, anteaters and sloths, though in contrast to some of its relatives, Mylodon did not burrow or climb trees. Remains have been found throughout South America, demonstrating the animal was adaptable to cold climates.

At the crack of dawn, I’m picked up at my hotel by Maximiliano Valdivieso, a guide who will take me to Mylodon cave located outside the city. Several hours later, feeling out of sorts from lack of sleep, I got out of the minivan in the middle of a rainstorm. A path leads us alongside a dramatic cliff face, and to one side I take in life-size models of Mylodon, as well as illustrations of other ancient megafauna which roamed the area, such as Macrauchenia, which Darwin regarded as a “prehistoric llama” and saber-toothed tigers.

He “realized he had been looking for a ghost, a unicorn, an animal that had been extinct for thousands of years. It was Mylodon.”

Discovered in 1895 by German explorer Hermann Eberhard, Mylodon cave contained exceptionally well-preserved remains including pieces of skin, fur and dung. As we make our way into the vast cavern, my guide explains how Eberhard dissected samples and sent them to England for analysis. In the meantime, however, the German hunted in vain for the animal, surmising it might still be alive since the remains were in good condition. When the results came back, however, he “realized he had been looking for a ghost, a unicorn, an animal that had been extinct for thousands of years. It was Mylodon.”

Gigantic sloth, extinct mammal of the Pleistocene Epoch, drawing (Getty Images/DeAgostini/Getty Images)And yet, how did researchers identify the animal? Fortuitously, they were able to compare Eberhard’s sample with Darwin’s original fossils from Argentina, noting a resemblance. Peering into dark recesses of the cave, I wonder what might have caused Mylodon’s demise? Valdivieso says arrowheads were uncovered, indicating early human presence.

Gigantic sloth, extinct mammal of the Pleistocene Epoch, drawing (Getty Images/DeAgostini/Getty Images)And yet, how did researchers identify the animal? Fortuitously, they were able to compare Eberhard’s sample with Darwin’s original fossils from Argentina, noting a resemblance. Peering into dark recesses of the cave, I wonder what might have caused Mylodon’s demise? Valdivieso says arrowheads were uncovered, indicating early human presence.

Could human hunting have played a role, or were there other factors? Rewind more than a month earlier, and I find myself in Montevideo. During his travels in Uruguay, Darwin uncovered fossils belonging to Glossotherium, also known as the “tongue beast,” another species of giant sloth. Hoping to learn more about Darwin’s ancient megafauna, I headed to a storehouse linked to Uruguay’s National Museum of Natural History. Shortly before my arrival, the museum had put on an exhibit dealing with Darwin’s legacy in the country. Andrés Rinderknecht, a paleontologist, provided me with a tour of the fossil collection.

Archaeologists have uncovered early pendants made of bony Glossotherium material, suggesting humans may have played a role in the creature’s demise, however Rinderknecht says the jury is still out on whether hunting, climate change, or even other factors may have dealt the crucial blow.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

Are there lessons for the present day? Extant animals like giant armadillos and giant anteaters, related to Darwin’s ancient giant sloths, have experienced similar pressures. Indeed, the former has been listed as endangered, and in Uruguay the animal has been hunted while suffering habitat loss. Giant anteaters, meanwhile, are listed as vulnerable and have been targeted by poachers. There is little knowledge of local fauna, Rinderknecht remarks, and coastal ecosystems have become a “disaster” due to urbanization.

“We recently experienced the worst drought in one hundred years,” the paleontologist adds, and Montevideo was hit by a lack of potable water. On the other hand, Uruguay has a historic secular streak, and though the current conservative government isn’t wholly supportive of science, at least officials recognize the reality of climate change.

After concluding my business in Montevideo, I took a short ferry ride to Buenos Aires. In the midst of a suffocating summer heat wave, I paid a visit to the “Bernardino Rivadavia” Argentine Museum of Natural Sciences, where I spoke with paleontologist Agustín Martinelli. In addition to Mylodon, Darwin uncovered fossils in Argentina belonging to another giant sloth species, Megatherium. Though the creature had already been described by science, researchers lacked significant specimens to inspect until Darwin happened upon a Megatherium skull. Martinelli himself was inspired to become a paleontologist after growing up as a young boy near the Luján River, where Megatherium remains had been discovered.

Upstairs, walking through an exhibit dealing with ancient megafauna, I was non-plussed by the sheer scale of a Megatherium skeleton — indeed, the creature weighed up to four tons and grew to the size of an elephant while consuming vast quantities of vegetation daily. As with Glossotherium, it’s unclear what caused Megatherium’s demise 12,000 years ago, though some believe climate and hunting played a role. Megatherium is related to present-day sloths, which face climate and environmental pressures. Currently, Martinelli remarks, sloths are restricted to northern Argentina and Brazil, though the creatures are at ecological risk. Meanwhile, though giant anteaters have successfully been released back into the wild, giant armadillos are extremely threatened.

Argentina’s political environment, meanwhile, leaves something to be desired and provides a stark contrast to Uruguay, where there is more support for science. Just before I arrived, the country elected Javier Milei to the presidency, a rightist politician and climate denier. Milei is highly volatile and unpredictable, Martinelli remarks, and he and his scientific colleagues are concerned for the future. Even within the museum itself, Martinelli says, they do not have the proper means to regulate indoor temperature. Outside, meanwhile, the climate in Buenos Aires is becoming more and more tropical.

Fast forward to Chile, and I’m thinking more broadly about human folly and our inability to protect native wildlife. After visiting the Mylodon cave, I took in majestic mountains and glaciers in Torres del Paine National Park. Struggling to hear amid high winds, my guide Valdivieso explained the region had witnessed high temperatures and a lack of rain, with hundreds of small lagoons drying up, which in turn had a ripple effect on wildlife.

“I’d never seen anything like that in my life,” he said, “which startled and alarmed me.” I, too, was taken aback by the sight of burnt patches of trees. Local fires linked to human error and carelessness, Valdivieso explained, have become more intense and difficult to extinguish.

We need your help to stay independent

Back in Punta Arenas, I caught up with Juan Francisco Pizarro, a government biologist, who was inclined to believe Mylodon succumbed to both hunting and climate pressures. Considering current environmental problems, he remarked, Mylodon cave should not be considered a “mere curiosity.”

Pizarro remarked how Punta Arenas, the most southerly city in the world, has been experiencing strange weather patterns. Just that morning, in fact, he had remarked to his family how Punta Arenas had gone through two days of rain, though it wasn’t cold but rather quite humid with temperatures ranging in the mid-60s. That is the type of summer weather one might expect far to the north, in more temperate areas of Chile.

On the other hand, in contrast to climate-denying Milei, the government in Santiago has sought to prioritize the environment and Pizarro praised Chile’s president Gabriel Boric for his efforts. And what would Darwin have made of climate change? The naturalist observed how species can adapt to such change over long periods of time, Pizarro remarks, but now the climate is changing at a more accelerated pace. Given previous extinctions of megafauna such as Darwin’s giant sloth, and humanity’s inability to protect current day wildlife, it’s not clear whether valuable lessons have been learned.

Shares