Picture this, it’s 1998 and you’re called to the principal’s office. Not because you flung paper clips at the substitute teacher again, but because your deskmate who has been missing since this morning went home thanks to head lice. Now, the school nurse is tasked with checking your head. Sorting strand by strand to see if tiny, six-legged insects are clinging to your scalp.

If they are, your future includes a missed day or two of school. If not, you’ll live in fear of every little head itch over the next couple of days. What remains a peculiar childhood memory for many, no longer exists for today’s school-aged kids, and that’s because the guidance on how to handle lice in an educational setting has changed. As kids return to school, they embark on yet another year where school nurses will continue to debunk and destigmatize head lice.

“It just doesn’t make sense, if you think about the life cycle of the lice, to send a kid immediately home when you see it, when it's very likely possible that they've already been infected for three weeks or so,” Lena van der List, a general pediatrician from the University of California-Davis Children's Hospital, told Salon in a phone interview. “It’s not very easily transmissible between children, and it’s misdiagnosed frequently by non-medical professionals.”

When people think they're seeing lice, van der List said, they are just casings of these nits that aren’t alive. Head lice, scientifically known as Pediculus humanus capitis, are tiny parasitic insects that feed on blood from the human scalp; they most frequently affect kids. The wingless insects usually spread through direct contact from the hair of one person to the hair of another. Notably, research has shown that head lice are not a significant health hazard or a sign of poor hygiene.

“Despite this knowledge, there is significant stigma resulting from head lice infestations in high-income countries, resulting in children and adolescents being ostracized from their schools, friends, and other social events,” the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) states. “Head lice can be psychologically stressful to the affected individual.”

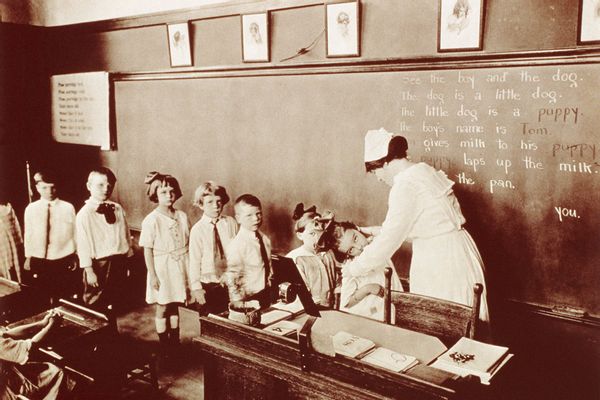

A nurse examines a group of school children in New York. She is looking for head lice. (CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)Hence, a change in guidance over the years. According to the AAP “no healthy child or adolescent should be excluded from school or allowed to miss school time because of head lice or nits.”

A nurse examines a group of school children in New York. She is looking for head lice. (CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)Hence, a change in guidance over the years. According to the AAP “no healthy child or adolescent should be excluded from school or allowed to miss school time because of head lice or nits.”

“Medical providers should educate school communities that no-nit policies for return to school should be abandoned, because such policies would have negative consequences for children’s or adolescents’ academic progress, may violate their civil rights, and stigmatize head lice as a public health hazard,” the AAP’s policy, which was released in 2022 states.

In February 2024, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also updated its guidelines stating “You do not need to send students with head lice infestation home early from school.”

"No healthy child or adolescent should be excluded from school or allowed to miss school time because of head lice or nits."

“Students with lice can go home at the end of the day, be treated, and return to class after beginning appropriate treatment,” the CDC states. “Nits may stay in hair after treatment, but successful treatment will kill crawling lice.”

Leaving kids with lice in school might sound outrageous to those who were banned from classrooms in decades past, but experts say it’s a reflection of our changing understanding of lice. For example, people used to believe that lice could jump from head to head, but that’s not true. However, a Washington Post article did point to selfies as a possible source of contagion, because putting heads together and leaning in to take a snapshot seems to give the bugs that opportunity.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

“If someone has a hat, or wears a hooded sweatshirt or coat that hangs on a hook right next to somebody else's coat, so they touch, the head lice can transfer over that way,” Kate King, a school nurse at a middle school in Ohio and president of the National Association of School Nurses, told Salon. “I wouldn't say they're highly contagious, they certainly can move from one space to another, but they do not jump, and they do not fly.”

Nobody likes to think that insects are crawling all over their heads, King added. It’s “kind of gross,” but it’s “not a high risk for disease or any other sequelae.”

Head lice used to be listed as a communicable disease, and had to report it to the Health Department, King added.

We need your help to stay independent

“We want to look at this as helping people get rid of head lice, versus stigmatizing and saying, ‘You have to go home, you can't come back to school,’” King said. “We really want children to be in school, to feel comfortable in school, and not to be excluded for something that they don't need to be excluded for.”

Van der List said the “parental workforce” has also changed the approach to managing head lice, alongside rising concerns about absenteeism. Previous guidance to send children home immediately “really hurt families,” she said, and “for no real good reason.”

Plus, over-the-counter treatments are effective.

“Over-the-counter treatments are great,” she said. “But in the very rare case that you're having this kind of persistence, you do want to talk to your physician because there might be a prescription needed.”

But rarely, head lice require a call to the doctor anymore.

Shares