James Earl Jones introduced me to August Wilson by way of his play “Fences.” Our acquaintance was forged indirectly and vicariously, I should say, through my mother. In 1986, Mom was a season ticket holder with the Goodman Theatre in Chicago, where Jones starred in a pre-Broadway run of Wilson’s plan.

Mom attended a lot of Goodman productions, but Wilson’s play is the only one she couldn’t stop talking about for years, due to the writing and Jones’ anchoring presence. “Fences” was the playwright’s third production, and by the mid-‘80s, Jones was already a bonafide star, having completed his arc as Darth Vader in the first “Star Wars” trilogy and played Alex Haley in the groundbreaking miniseries “Roots” and “Roots: The Next Generation.”

Darth Vader wasn’t Jones’ first father role for the big screen; in John Berry’s 1974 feature “Claudine” he co-starred with the late Diahann Carroll as Roop Marshall, a charming municipal waste collector who falls behind on child support.

Thanks to George Lucas tapping in to provide the voice of the films’ great villain, however, he held separate identities in the minds of children and their parents. To the young, his voice could be synonymous with authoritative menace or vast warmth, depending on the circumstances of their first encounter. His cameo on "The Big Bang Theory" encapsulates both sensations in a single, wonderful interaction.

“Fences,” I came to understand much later, provided Jones an opportunity to originate another kind of father, Troy Maxson, burdened with a different type of destiny. Wilson’s lead is a working-class Black man, a former Negro league superstar whose dreams festered when baseball’s color barrier prevented him from rising into the big leagues.

In his remembrance of Jones, a Grammy, Emmy, Tony and honorary Oscar winner who died Monday at the age of 93, Chicago Tribune critic Michael Phillips recalls the actor explaining Troy Maxson’s appeal in their long-ago conversation. “This is a character who comes on the stage representing something hopeful, especially for the Black female,” Jones said. “He’s a strong man who has the chance to make something happen right, rather than just (mess) up.”

Then he does mess up, Jones continues. “It’s the last thing they want to see,” he told Phillips, “because the audience has gotten pretty wrapped up in the play by then.”

This, at last, explains why my mother was so taken by Jones' performance. By 1986 she and my father were divorcing, and hideously. And there was Jones, a tower of a man, breathing warmth and dignity into this flawed man worked over by life but still trying. Still doing right by his children, which must have been the least of what she wanted from her dispiriting situation.

Memory is tricky, though, and perhaps that emotional context didn't enter her evaluation of the experience at all.

Either way, a scene from its Broadway performance is still making the rounds featuring Jones' Troy dressing down his son Cory – played by Courtney B. Vance, another incredible talent – for having the temerity to ask his father why he never liked him. Jones pours all his passion into his response, ensuring the scene is carved into whatever monument to stagecraft might exist. Denzel Washington played Troy Maxson in the movie version of "Fences" in 2016, and if you thought his work was excellent, that's probably because he had a mountainous standard to meet.

The multitude of tributes to Jones that have come out in the days since his death tend to lead with references to his voice, and well they should. There are indelible voices in entertainment, and there is James Earl Jones’ baritone, variously described as sonorous, commanding, and booming.

It is a voice that erupted from beneath the thick mantle of a difficult childhood, nearly muted by a stutter that a teacher taught him to overcome by forcing him to read a poem aloud. He says this made him realize performing the written word was his path to moving the world.

This happened long before “Star Wars” changed how a generation saw him, before “The Lion King” introduced him to Millennials as Mufasa, Simba's father and the rightful and just ruler of the African savannah. News-watchers recognized him as the voice of CNN. Om is said to be the mantra describing the sound of the universe. Likening the music produced by Jones’ golden vocal cords to that would be pushing it, we know.

But Jones’ timbre perhaps gave voice to something universal, a sound to nobility and resplendence. That was true whether he was playing kings, garbage collectors, or a hope-weaving author, as he did in “Field of Dreams” – or one of the many fathers he brought to life on stage, in movies, or in the many TV series in which he appeared or starred, including the short-lived ABC drama "Gabriel's Fire," for which he won one of his two primetime Emmy awards.

Inimitable voices might stay with us for a time, but it’s the vessels, the deliverers, who might ensure their immortality.

If it seems to many of us that Jones has been with us since we were in our cradles, that’s because he was. Before his first major Hollywood breakout, he became part of the test run for “Sesame Street,” seen in a 1969 video clip of him reading the alphabet.

That appearance was one of many over the years, and made him the show’s first celebrity guest, although it was recorded a year or so before he starred in the movie adaptation of “The Great White Hope.”

By then Jones had already won a Tony for playing the role on Broadway as well as playing roles on TV shows like “Dr. Kildare” and “N.Y.P.D.” The movie added a Golden Globe (for most promising newcomer-male) along with an Academy Award nomination, although review averages on sites like Metacritic and Rotten Tomatoes sit on the lower edge of middling.

We need your help to stay independent

It could be that modern critics and audience reviewers are evaluating it from the stance of those already deeply versed in the actor we know from modern movies, such as the “Field of Dreams" author Terence Mann, who transformed from a disillusioned hermit to a revitalized believer.

Those came years after Jones learned to calibrate that voice and energy to reach not to the back row but into our spines and souls. Still, within his Jefferson lives a version of William Shakespeare’s Othello, another part Jones played to great acclaim with Christopher Plummer as his Iago.

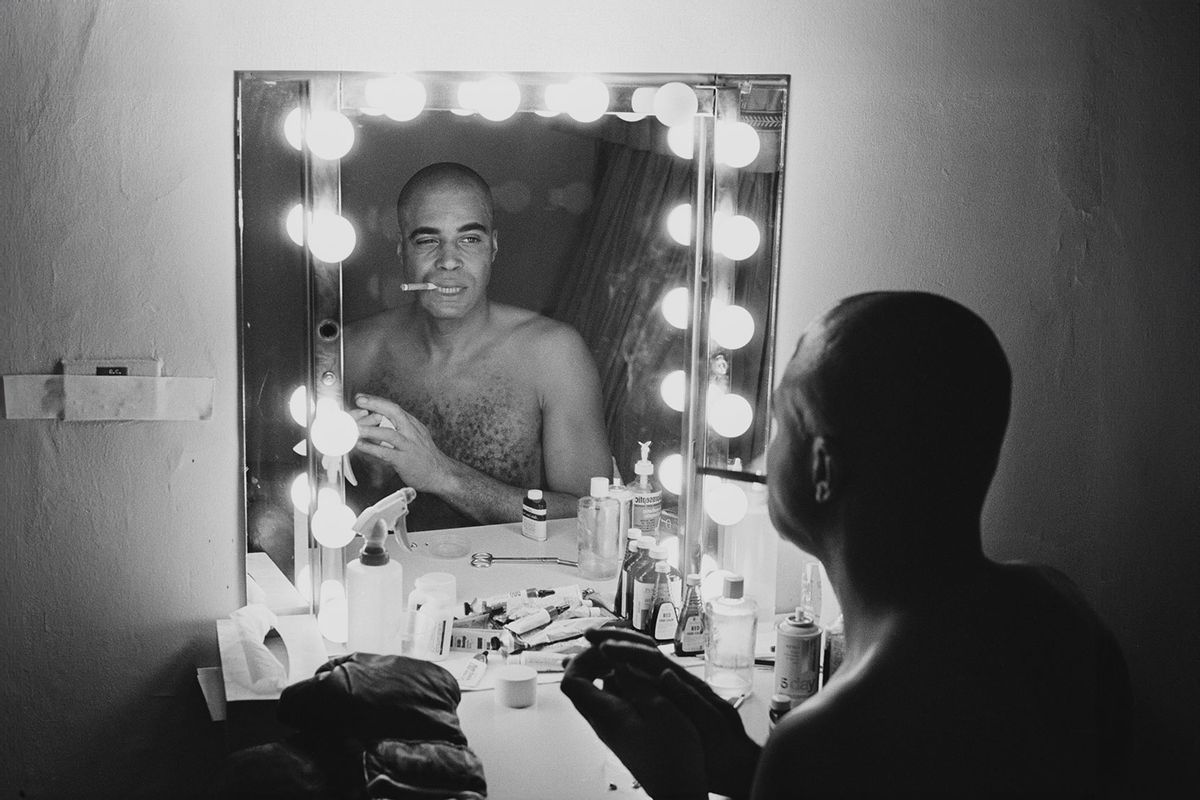

Jones was 6 foot 2 inches tall and put his muscular chest into everything whether via a quiet push, as when he growls “All I got to do is be Black and die, lady,” or a roar — as when his Jefferson, exiled from this home country, pounds his chest in frustration and screams at the sky.

Maybe that movie was too small to contain his thunder. Still, in that performance, one can appreciate the luxury of the tight shot on Jones’ face, a panoply of expressive glowing and fading between pride, joy, anger and sorrow that only theatergoers in the good seats might have been able to fully experience. Jones’ glower could chill you to the bone, but his smiles were radiant and honest. His “people will come, Ray” speech from “Field of Dreams” is preserved in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum's permanent collection, in addition to being imitated at countless auditions.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

The real magic, however, is the giddiness sparkling around Terence Mann who starts as a lost soul and ends the film believing in magic again, simply by touching the edge of a cornfield.

His “Field of Dreams” character and the man he played in “Fences” have in common an intense love affair with baseball, the sport romanticized for the way it connects us to our personal and shared histories. This, too, reflects the actor’s ultimate legacy.

The voices we never forget tend to come out of incredible performers, and we’ve gotten several tremendous ones within the last two years, including Andre Braugher and Lance Reddick – two other actors whose tone and cadence we can still hear if we listen hard enough to memory, and who were undoubtedly inspired by Jones.

“August Wilson, it is clear, can write like an angel,” the Tribune's reviewer concluded in 1986.

The same article cites Jones’ performance as integral to making Troy Maxson “a man of almost mythic power and nobility who, despite personal failings and life’s limitations, is still fit for heaven’s gates.” The playwright’s words can transport us, but only a monumental performer like Jones’, in body and voice, can propel his sentiments aloft.

Shares