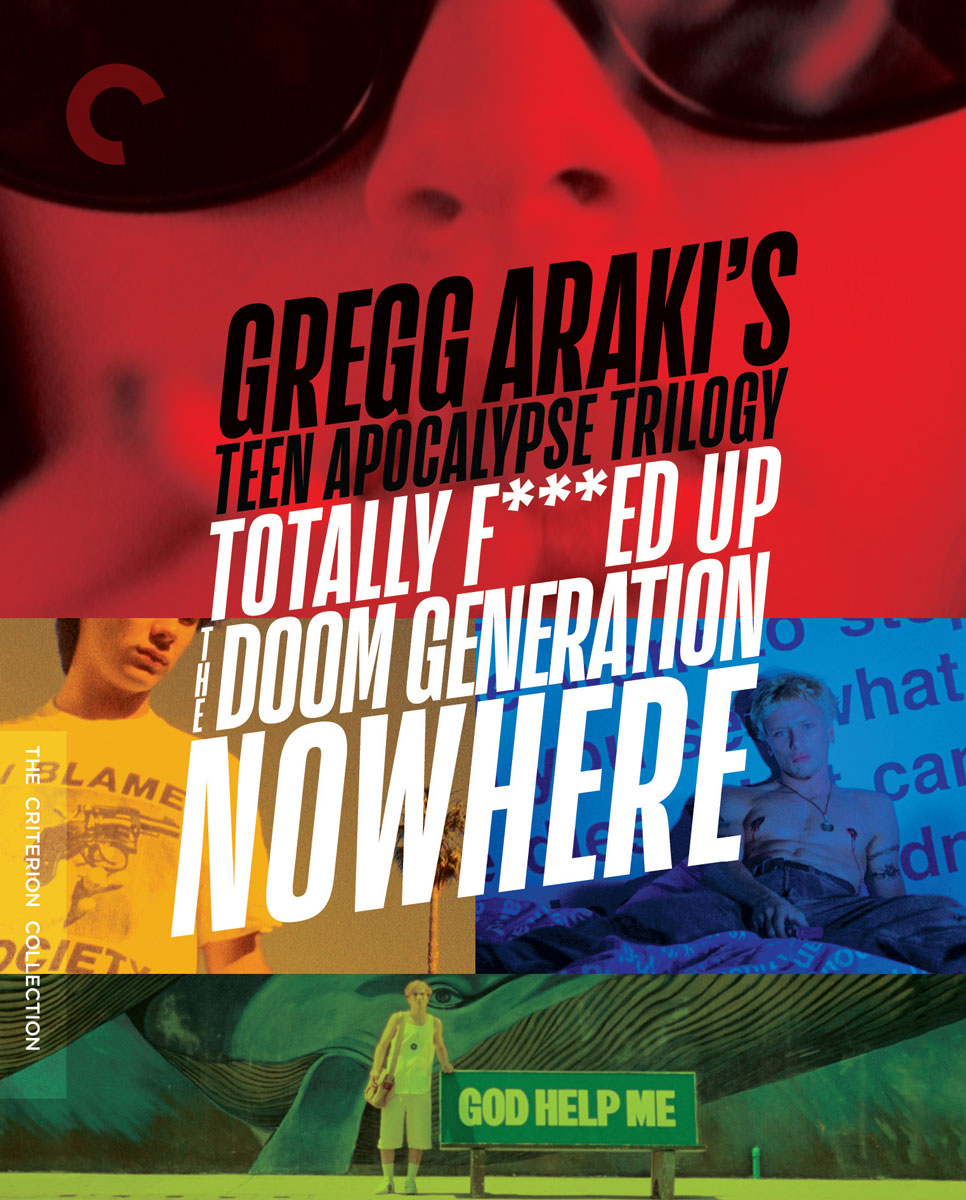

Gregg Araki followed up his 1992 breakout hit, “The Living End” — about two HIV+ lovers (Craig Gilmore and Mike Dytri) on the run — with his “Teen Apocalypse Trilogy.” These three films — “Totally F***ed Up,” (1993) “The Doom Generation,” (1995) and “Nowhere,” (1997) — are now getting released as a set by the Criterion Collection in a 4K UHD + Blue-Ray Special Edition on September 24. It is the perfect time to revisit these gems about jaded teens trapped in a hedonistic vortex.

The six queer teens in “Totally F***ed Up” struggle not with their sexuality — at a time when it was dangerous to be openly gay — but with finding and keeping love. The emotions ring true as the characters experience sex and setbacks, and Araki films “Totally F***d Up” with dramatic scenes as well as the actors talking in direct address as they play out their romances and hookups.

“The Doom Generation” has a different tone as lovers Jordan White (James Duval, who appears as the lead in all three films) and Amy Blue (Rose McGowan) meet Xavier Red (Johnathon Schaech) one fateful night. After a murder occurs, the trio hit the road, holing up in cheap hotels for sex and a series of bizarre and violent encounters. Araki’s lurid film culminates in a shocking episode, brilliantly shot with a strobe effect.

“Nowhere” is far more playful as more than a dozen teens try, with varying degrees of success, to have sex. Perhaps it is the overwhelming sense that “the end is near” that prompts the characters to explore their sexual fantasies, but “Nowhere” is easily the horniest film in the trilogy—quite an accomplishment given the palpable sexual tension in “The Doom Generation,” and all the desire on display in “Totally F***ed Up.”

But what is most notable about the Teen Apocalypse Trilogy is Araki’s brash, take-no-prisoners style, which plays up both the gore and the sexuality in equal — and at times offensive — measure. The dialogue consists of teen angst vernacular, and it can be off-putting too, with rude insults and numerous euphemisms for sex and genitalia. But this —call it childish glee — is part of Araki’s style along with his fabulous soundtracks (The The, My Life with The Thrill Kill Kult, and Cocteau Twins, etc.) and fun celebrity cameos (Christopher Knight! Lauren Tewes! Heidi Fleiss!).

These films separately and together provide a shrewd snapshot of 1990s nihilism. Araki spoke with Salon about his teenage angst and his "Teen Apocalypse Trilogy."

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Did you set out to make these films as a trilogy, or did it happen organically?

It was very organic. “Totally F***ed Up” was its own thing. I wanted to do a queer remake of “Masculine/Feminine,” which is probably my all-time favorite Godard movie. [Araki named his characters in “The Living End” Jon and Luke after Jean-Luc Godard]. “Totally F***ed Up” was about the problems and issues young gay people were facing in the homophobic '90s. It was cast with non-actors. Gilbert Luna, who plays Steven, was the roommate of a friend of Andrea’s [Sperling, the producer]. We had a dramalogue. From there, the experience of making that movie — we shot for 6 months, because we were just shooting weekends — hanging out with those kids inspired me to make the other films in the trilogy. I wrote the parts in “The Doom Generation” and “Nowhere” for Jimmy [Duval.]

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

As someone who has been watching your films since the early '90s — I still remember seeing “Long Weekend (O’ Despair)” and “Three Bewildered People in the Night” at a film festival here in Philly — I wrote you and you sent me back envelopes with all these crazy designs all over them.

Save those, because when I die, they will be worth a fortune! I used to make these collages on my mail with pictures and captions. That’s cool that you’ve seen “Long Weekend.” That’s the rare movie, like a hidden Beatles album. “Three Bewildered People” played on PBS at like 2 o’clock in the morning and there are VHS copies floating around. It was screened at Outfest in 2000-something. But “Long Weekend” is super rare. One day I’m going to release it as an Easter Egg. People have seen everything but “Long Weekend.” Those that have seen it, like that 500 people — are true, true, true fans.

Yes, I think of the trilogy, I like “Totally F***ed Up” best because it gives me the feels I had watching “Long Weekend (O’ Despair),” “Three Bewildered People in the Night” and “The Living End.”

“Totally F***ed Up” is the most heartfelt and raw and primal, like my early movies.

How do you think these films — which deal with issues of queer teen suicide, homophobia, AIDS and ennui, during a time when it was dangerous to be gay — hold up now?

It’s interesting because it’s sadly still relevant. Things in the trilogy like the homophobia, AIDS-phobia, violence, and f***ing Nazis in “Doom Generation” should be so passe now. There is footage of Jesse Helms in “Totally F***ed Up,” and he is such an icon for that phobia and hatred. Thankfully he’s dead, now there are a million Jesse Helms. He’s bred like a hydra. There is gay marriage now, which is awesome, and more acceptance of queer people. Gen Z is very fluid and the stigma of being bisexual or pansexual is better than it was back then, but so many of those themes and the alienation — not just queer alienation but of being young, feeling different, and being an outsider — is almost more relevant today. It was so fascinating when Jimmy [Duval] and I were doing screenings that the audience was almost all new. So many young kids, like teenagers — I was wondering how do you know about this movie? It is interesting how the trilogy has lived on in the culture and been passed on like bootlegs. Now you can get it in 4K and it looks gorgeous. It’s amazing that these movies have lived on for so long and are still resonating with people.

What can you say about how you depicted queer teen sexuality and sexual fluidity back in the mid-1990s?

It’s funny because when we remastered “Living End,” in 2008 — that film was so controversial and shocking; the gay sex was so extreme. When I saw it in 2008, it was so quaint and so restrained. By 1990s standards — 1992 when we did “The Living End,” seeing two guys kiss was shocking. It was a different world. It was before “Will & Grace” and “Ellen.”

Yes, I couldn’t sleep the night before I saw “The Living End,” because I was so excited to see it. I recall just having to catch my breath during the scene with X on the bed in “The Doom Generation” because I just couldn’t take it. It was trailblazing at the time. We just were not seeing films like this back in the 1990s. The queer teen coming-of-age films were nothing like your movies. It was important you made these films for a gay audience.

It was very much me doing my own thing and expressing myself and doing things that no one else was doing. That was “Doom Generation” and “Nowhere” and “Totally F***ed Up,” too — nobody was making movies like that. Those movies have their influences, and they are clear, but movies like that are still very unique in the culture. This may be why younger audiences today are responding to them. You can’t just watch films like them on Netflix. There is a whole genre of film for queer young people, like “Red, White, and Royal Blue,” but it’s a big gap between those coming-of-age queer comedies and “Nowhere.”

That’s why I think the sex was really progressive. We didn’t see explicit sex, but it felt explicit.

I was looking at [Madonna’s] “Sex” book which came out in 1992, the same year as “The Living End,” which shocked me that it was that long ago. That notion of sex that is authentic and unapologetic and free. It wasn’t burdened with guilt or shame and anxiety. It’s more actual liberation that was such an important part of my upbringing and my sensibility and what I was feeling as a young person. I was not raised religious, and I am so grateful to my parents for that because I didn’t have that burden of fire and brimstone and guilt and you’re going to hell. It let me be free to explore myself and figure out who I was, what I liked, and who I liked. I wasn’t in that prison that so many young people are raised with.

Gregg Araki's Teen Apocalypse Trilogy (Courtesy of the Criterion Collection)One of the characters in “The Doom Generation” says, “There isn’t a place for us in this world,” suggesting how teens/queer youth feel. In “Nowhere,” Dark feels lost, and later says, “Our generation will witness the end of everything.” Can you talk about the theme of belonging in your trilogy?

Gregg Araki's Teen Apocalypse Trilogy (Courtesy of the Criterion Collection)One of the characters in “The Doom Generation” says, “There isn’t a place for us in this world,” suggesting how teens/queer youth feel. In “Nowhere,” Dark feels lost, and later says, “Our generation will witness the end of everything.” Can you talk about the theme of belonging in your trilogy?

People have told me that the trilogy movies have saved their life. They grew up in some sh***y town in some red state and it was a lifeline to see these people who were different. They felt like outsiders, or they didn’t belong. The notion that there is a world out there, and a chosen family, and a place for you — it’s just not in your sh***y town with all the homophobia and all the bigotry. You have to get old enough and grow up and escape and go to a place where there are people like you, or there is your chosen family and people can love and accept you for how you are. That’s very much a part of “Totally F***ed Up.” These six kids come together and make a family. In “Doom” and “Nowhere,” they don’t fit in in this world, but they are looking for where they do fit in and who they fit in with. That is such a huge theme of the trilogy and growing up.

The films all feature realism and surrealism and are different in tone and genre. Can you talk about striking a balance between showing things as they really are and telling stories that are outrageous, gory, and stylish?

It is definitely something I’ve always been interested in in my movies, this notion that cinema is so close to a dream world. David Lynch is, obviously, such a huge idol and his films have been such a huge influence on me. But this notion of being caught between dream and reality and what’s fantasy/not fantasy makes for a cinematic universe that is so expressive. I’m not a big fan of mumblecore and documentary realism with ugly lighting.

I notice the shift between these films in the trilogy and your earlier films. But then you played with this further with “Smiley Face” and “Kaboom!” that played with reality in ways that are more exaggerated….

I don’t go to the movies to see reality. I want to see a vision and escape somewhere. That’s why, as the trilogy wears on, the movies get more expressionistic and more stylized with the costumes, the sets and the colors. I don’t want to make reality, but the important thing though is that it is in a stylized, surreal world. The emotions and acting and what the characters are going through are all super-real to me. It is not making fun or camp. Those emotions are genuine and authentic. That is what makes the films resonate.

We have to talk about your incredible soundtracks. How does music inform your films?

Alternative music is such a huge part of my life. It’s my main source of inspiration. As an undergrad in college in 1978-82, there was literally the explosion of new wave music and punk rock. It all happened in the most formative period of my life. There was an explosion of creativity, rebellion and anti-establishment. Those new wave bands had all that androgyny and weird queer stuff going on. It was queer and cool to be different and the outsider. It was finding your tribe and family. This music inspired me to make movies. That’s why my movies are the way they are, because of those soundtracks. “The Doom Generation,” that was my Nine Inch Nails movie. I was into industrial music and was so angry. Every movie had a different vibe. “Nowhere” was pop psychedelic, Chemical Brothers and Britpop. “Splendor” was a whole electronica rave-y kind of vibe. As I was getting into all this music it was impacting the sensibility of the movies themselves. That’s why “The Doom Generation” is so intense.

I am guessing you were an angsty teenager? How do you think teens today can relate to your film?

Not as much as a teenager. More in my 20s and early 30s. Gus Van Sant [recalled] us meeting in this period, around 1989-1990, and what he remembered was me being so miserable at the time, smoking Doral cigarettes. I wore a tattered leather jacket. I was so full of existential angst, but that was what I was going through at that period.

Well, I’m glad you made these films so you could get it out of your system.

It is cool that these films preserve this. I am not like that anymore, but when I see these movies, it’s like, Holy S***! They are a time machine taking me back to who I was at that exact moment in my life. I am so grateful for the ability to do that and that the films still exist, now in glorious 4K.

“The Teen Apocalypse Trilogy” is available from the Criterion Collection on September 24.

Read more

about this topic