Shortly after Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential election, I contacted Alastair Smith and Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, the two NYU political scientists who, several years before that, co-authored a book entitled "The Dictator's Handbook," which outlines a novel theory of how political leaders — whether they are democratically elected politicians, unelected autocrats, or somewhere in between — acquire and hold onto power. I wanted to explore the question of what a Trump presidency might mean for the future of American democracy, which seems even more urgent eight years later.

My interview with Smith and de Mesquita, published in early 2017 by Salon, was surprisingly hopeful in tone. De Mesquita expressed the view that the United States is a “mature democracy,” and “mature democracies don’t become authoritarian.” Even though Trump had clear authoritarian and even fascist tendencies, the authors reassured me that our democratic institutions would survive — and in large part, they were right. Despite Trump’s “Big Lie” about the 2020 election and the Jan. 6 insurrection, Joe Biden took his seat in the Oval Office and reversed some of Trump’s anti-democratic policies, such as the “Schedule F” executive order aimed at turning the entire executive branch into a political instrument. While countries like ours may “oscillate a bit and become more or less democratic,” de Mesquita said, there has “never” in history been a mature democracy that has slid into authoritarianism, dictatorship or autocracy. It just doesn’t happen.

Well, OK. But what about this time around? What if Trump gets elected again? As many have noted, Trump entered the White House in 2017 completely unprepared for the job. That won’t be the case if he moves back in next January: Despite his disavowal of Project 2025, he will immediately begin to implement many of its proposals, most notably by replacing much of the “deep state” (i.e., nonpartisan federal employees who are hired and promoted based on competence and expertise) with MAGA loyalists. Trump has also threatened to punish political opponents, journalists and other voices of dissent, whom he has called “vermin” and “scum.” In July, he reposted an image on Truth Social calling for a televised military tribunal of former Republican congresswoman Liz Cheney, who voted to impeach Trump after the Jan. 6 insurrection and then helped lead the resulting congressional investigation.

Worse yet, the Supreme Court’s recent ruling on presidential immunity removes many barriers to potential presidential misconduct. If Trump returns to office, he could — according to some interpretations of that decision — literally order the assassination or imprisonment of his rivals with zero legal consequences. He could get away with almost everything he’s fantasized about doing since he was first elected. So there seems to be a significant and realistic chance that Trump could become an autocrat who rigs future elections, locks up dissidents and pursues vicious retribution against his perceived enemies.

Faced with mounting anxiety about the future of our democracy, I contacted Smith and de Mesquita once again to get their take on a possible Trump 2.0 administration. Since a second Trump term would almost certainly be much worse than the first, I was curious as to whether they had changed any of their views. Are they still hopeful, or do they now believe that Trump and his MAGA cronies could actually destroy our democracy and replace it with an autocratic state headed by Dear Leader?

Smith and de Mesquita told me that the biggest reason our democracy will survive [a second Trump term] is because Trump’s policies will likely cause so much damage that they’ll ignite massive protests, uprisings and unrest.

As with our first interview, the conversation was fascinating, insightful, unsettling and, yes, ultimately optimistic. They told me that, on the one hand, there’s virtually no chance that America will lose its democracy, even if Trump is elected and acts on his most destructive instincts, unconstrained by the law. Mature democracies just don’t collapse into authoritarianism, they insist, and that remains true today no less than it did in 2016. On the other hand, Smith and de Mesquita told me, one of the biggest reasons that our democracy will survive is because Trump’s policies will likely cause so much damage that they’ll ignite massive protests, uprisings and unrest across the U.S., ultimately leading to his downfall.

As Smith told me when we spoke last month, people “should have concerns” about what Trump will do if he regains power. But it’s precisely “because of those concerns," he continued, "that Trump destroying our democracy isn’t going to happen.” He added: “I envision the number of people who would be demonstrating if Trump wins the election, if the Republicans were to win both houses, making Tahrir Square in Egypt — the 'Arab Spring' demonstrations in 2011 — look small. And those protests succeeded in bringing down the autocratic Mubarak government.” If Trump tries to restrict voting, as he probably will, that will only further energize the pro-democracy opposition. Ultimately, Trump's efforts to seize and hold power “will fail,” de Mesquita told me, for the same reason that public pressure during the 1960s ended the Jim Crow laws and ended legal segregation.

We need your help to stay independent

Perhaps surprisingly, the authors don't believe that only those on the political left will protest a future Trump administration. “Even among his supporters,” de Mesquita said, “they would quickly see how bad another Trump presidency was for them. … They’d see their welfare diminished, and will be on the streets” with everyone else. In other words, Trump 2.0 will likely be so disastrous that Trump will lose some of his base. They might still support his alleged policies, to some extent, but they will be so negatively impacted by the broader decline of our country that they’ll turn against the man they voted for. This has already happened to some extent, as Smith notes:

I remember, four years ago, biking around up in the Catskills where I love to go, and there are some neighborhoods that are clearly Trump neighborhoods. There were some spectacularly good displays of Trump flags and “melt the snowflakes,” etc. — displays on the side of the street, very creative stuff. I mean, not that I agree with it! But it was spectacularly well done. Things hanging from cranes with “Go Trump,” everything. This year, I’ve noticed those neighborhoods — there are very few signs up. Just a lot of people who backed Trump and probably still sort of like the policies he had. It’s just like, they don’t want to erode the democracy that they have.

I asked Smith and de Mesquita to elaborate on why they feel so confident that U.S. democracy would survive a second Trump term. Couldn’t the “democratic backsliding” that we’ve seen in Hungary and Poland — or, heck, the backsliding seen in Germany during the Weimar Republic — happen here, too? Why exactly has no “mature democracy” ever collapsed into autocracy, and why couldn't that change?

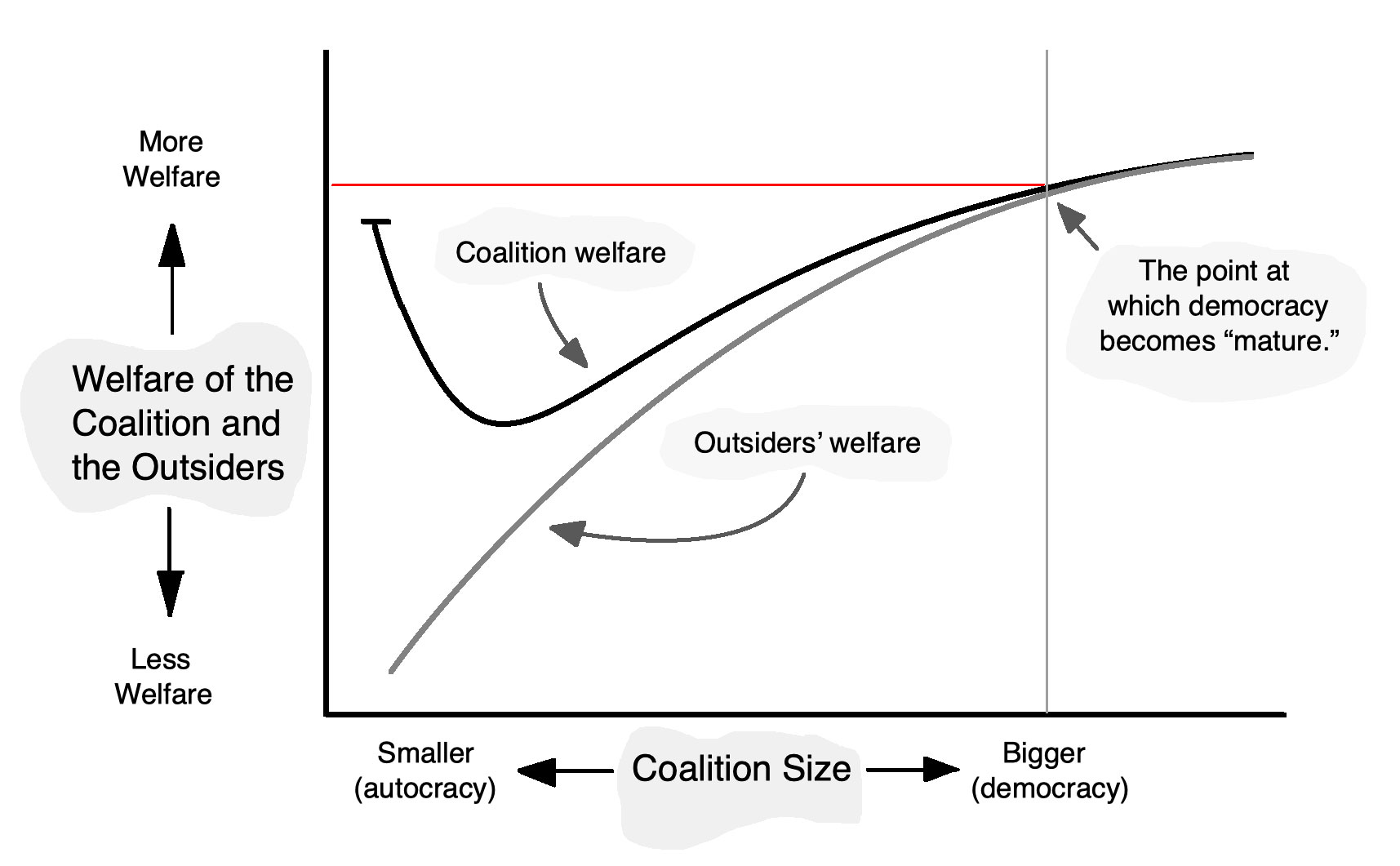

A key part of their explanation comes from the “swoosh” graph below, which Smith and de Mesquita present in the 2022 edition of "The Dictator’s Handbook." (I present a modified version here, with their approval.) This graph is deceptively insightful, and once you understand what it means, you might come to share their confidence as well.

On the up-down axis is the welfare of two groups: the "coalition," meaning those who support the political leader in power, and the "outsiders," meaning those who oppose the leader. On the left-right axis is the size of this coalition of supporters.

(Émile P. Torres)In an autocracy, all that’s required for the leader to stay in power is for him or her to keep a small group of cronies happy — think of the oligarchs and military leaders in Vladimir Putin’s Russia, or the inner circle of Kim Jong-un’s North Korea. The leader secures the loyalty of this tiny coalition through corrupt practices, often heavily taxing the outsiders (in other words, most of the society) and then redistributing this wealth to cronies in the form of “private goods” for them. Hence, the essential supporters of these autocrats are given special access to expensive cars, luxury apartments, the best schools for their children, family vacations on the beach and so on. For the cronies, life is pretty darn good, while everyone else in society struggles to get by.

(Émile P. Torres)In an autocracy, all that’s required for the leader to stay in power is for him or her to keep a small group of cronies happy — think of the oligarchs and military leaders in Vladimir Putin’s Russia, or the inner circle of Kim Jong-un’s North Korea. The leader secures the loyalty of this tiny coalition through corrupt practices, often heavily taxing the outsiders (in other words, most of the society) and then redistributing this wealth to cronies in the form of “private goods” for them. Hence, the essential supporters of these autocrats are given special access to expensive cars, luxury apartments, the best schools for their children, family vacations on the beach and so on. For the cronies, life is pretty darn good, while everyone else in society struggles to get by.

Trump 2.0 will likely be so disastrous, the authors claim, that Trump will lose some of his base. They might still support his policies, but they will be so negatively impacted that they’ll turn against the man they voted for.

If this coalition expands, the number of people the leader would need to keep happy will also increase. As a result, the welfare of the leader’s cronies begins to decline. Why? Because there’s only so much money for the leader to throw around, and the more people there are on the gravy train, the less there is for each individual insider. People in the coalition, therefore, oppose such an expansion: They don’t want to share the private goods they’ve become accustomed to receiving. It’s a kind of local minimum in which autocratic societies sometimes get stuck, although it’s not impossible to escape that trap, and in fact the number of autocratic countries has declined over the past century and a half while the number of democratic countries has risen. (Nearly everyone lived in autocratic states in 1850, while just over 50% of countries today are more or less democratic.)

So moving from the left side of the graph to the right side is painful for the leader’s supporters, who will likely resist this transition. It’s clearly not in their interest to share their private goods with a new group of folks. But if the coalition’s size keeps expanding long enough, past that big dip in the graph, living conditions will start to improve — not just for the supporters, but for the opposition as well. Why? Because, if the political leader wants to stay in power, he or she will have to keep an ever-larger number of people happy. The best way to do that is to implement policies that provide “public goods” that benefit society in general, in contrast to private goods that go to only a few people in particular. If you’re Kim Jong-un, you only have to please a few hundred people or so. But if you’re president of the United States, you have to please, at a bare minimum, many millions of people to keep your job.

To put this a different way, it would be far too expensive to give out special benefits and private goods to all your supporters, because there are just too many of them. Instead, you begin to implement policies that make everyone (or at least a majority) better off, which by definition also benefits your supporters. If this works, it keeps your supporters happy enough to vote for you again the next time around, and might also lead some non-supporters to flip sides. As Smith told me during our conversation, such public goods include a wide range of things, including “national defense and a clean environment and law and order and efficient highway systems and those kinds of communications and … freedoms.” Society becomes more productive, in other words, and everyone wins.

The shift from the left side to the right side of the graph corresponds to the political process of democratization, meaning that more people get a say in whether the leader stays in power and, in turn, that whether they remain in power largely depends on the type and amount of public goods they provide the people. Such goods are the only feasible way to improve the lives of your supporters, while also — by virtue of these being public goods — benefiting members of the opposition. That’s why everyone wins: Democracies are good for most people in society, whereas autocracies, by and large, are only good for a small group of elites.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

This leads us to one of the most important parts of Smith and de Mesquita’s graph: the inconspicuous gray line on the right. Look at where it intersects with the welfare lines of the “coalition” and “outsiders.” Then follow the horizontal pinkish line to the far left side of the graph. Notice that the welfare of everyone in society, to the right of the gray line, is better than the welfare of even the most privileged supporters in an autocracy, on the far left. In other words, the average person is overall better off in a highly democratized state than even the most privileged cronies in a dictatorship.

Smith and de Mesquita classify any country that falls to the right of that gray line as a “mature democracy,” and their surprising claim is that it has never happened that a country in that position on the graph has slid all the way to the far left — no mature democracy has ever become an autocracy.

Trump could cause the collapse of democracy after all — not because the U.S. will slide into authoritarianism, but because modern civilization as a whole will crumble amid the climate catastrophe.

The reasoning behind this makes sense as they lay it out: As the coalition supporting a would-be autocrat becomes smaller and the society becomes less democratic, money collected by the government is increasingly diverted from funding public goods to the “pet projects or secret bank accounts” of the leader, to quote Smith and de Mesquita in "The Dictator’s Handbook." As de Mesquita told me during our recent conversation, “When you’re past that point where the gray line intersects with the other two lines … you can’t make the coalition better off by shrinking it. You can’t even make a few of its members better off by shrinking it, and you can’t make the people better off, either. Only the leader can get better off.” So that kind of shift is likely to produce significant resistance from everyone, including, eventually, the leader’s own supporters.

So Smith and de Mesquita believe that the probability that our democracy will collapse during a possible Trump 2.0 presidency is virtually zero. Yes, Trump will almost certainly try to force the U.S. from the right of the graph to the left — and he may succeed to some unpleasant extent. But his policies will hurt so many people that even folks in the MAGA movement, they believe, will start to defect. His autocratic efforts will ultimately fail as tens of millions of people protest in the streets every month. And if you don't believe that such protests can be effective, Smith would point out, once again, that the mass protests in 2011 in Egypt did take down the autocratic regime of longtime president Hosni Mubarak. He summarized this point in our conversation:

Just think about the level of accountability. If we made the president accountable to fewer people, then the president's policies take on a "private goods" flavor. There are more corruption opportunities for cronies and less work and fewer resources are directed to rewarding the people. So you have to make this trade-off. Imagine being a Trump supporter: If you let Trump have a smaller coalition, he’s going to produce fewer public goods. Now, you might get more private goods, but fewer of the resources are going to reward you, and more are going to reward Trump and his private agenda.

So the way the trade-off goes, particularly in a productive society, is that you would be better off getting no private goods but getting the public goods under the opposition leader, rather than taking this mix [of slightly more private goods but much fewer public goods]. So you might like the policies under Trump, but Trump’s not working very hard — as opposed to, under Biden or Harris you might not like the policies, but they’re working hard to produce public goods for you.

The fact that mature democracies don’t collapse into authoritarianism, even under the leadership of wannabe dictators like Donald Trump, points to a crucial asymmetry in the graph: While autocracies can and do become democracies, and while some democracies can become autocracies, mature democracies never cross from the far right of the graph to the far left. This should give progressives and liberals, who fear Trump’s threat to our country, reason for hope — although, as Smith and de Mesquita made clear during our conversation, a Trump 2.0 presidency would self-destruct precisely because of all the terrible harm it would cause. So buckle up.

Even if our democracy can survive another Trump electoral victory, there are plenty of other reasons one might worry about America’s future. The most obvious of those concerns climate change: If Trump returns to the White House, he will almost certainly dismantle most or all climate mitigation efforts, as expressly advocated by Project 2025. Perhaps, then, he could cause the collapse of democracy after all — not because the U.S. will slide into authoritarianism with Trump on a golden throne, but because modern civilization as a whole will crumble amid the climate catastrophe. In either case, the authors of "The Dictator's Handbook" argue that even Trump supporters will lose if he wins. Let's hope enough of them figure that out.

Read more

about Trump and the topsy-turvy '24 race