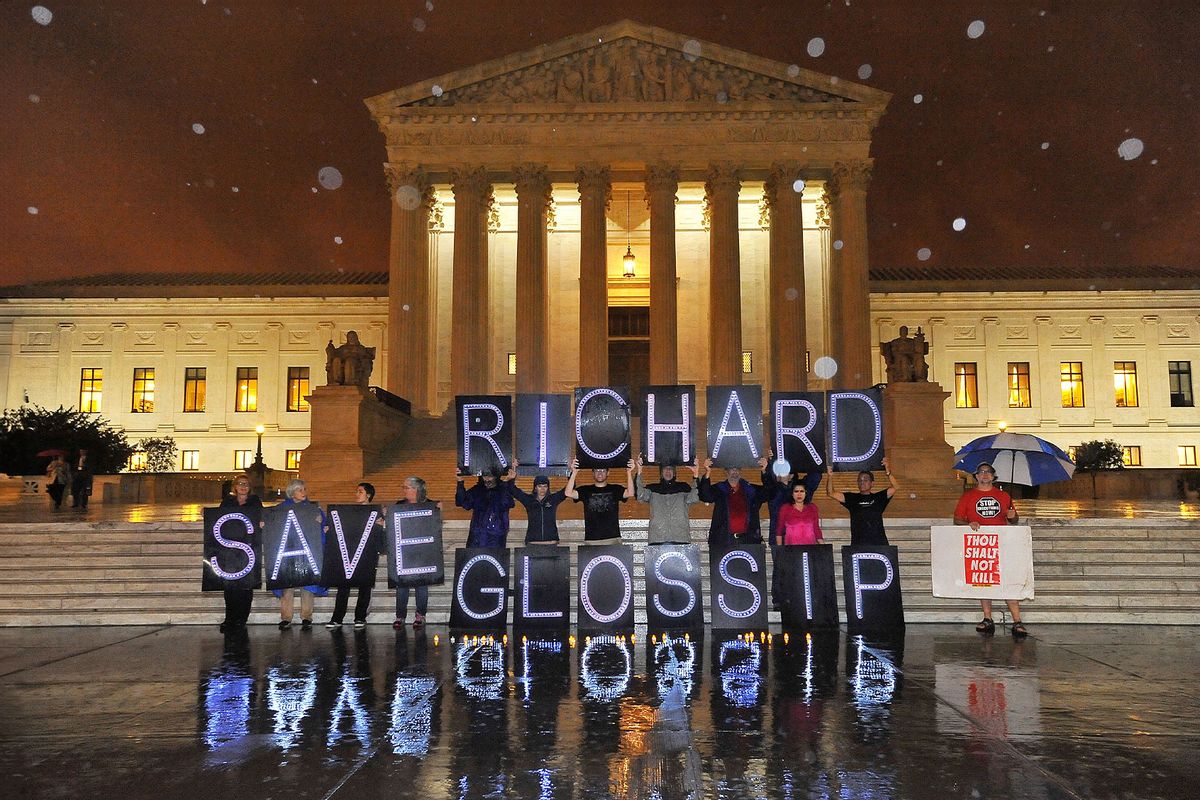

The Supreme Court on Wednesday heard oral arguments in a rare capital punishment case that's seen the Oklahoma attorney general side with death row inmate Richard Glossip's request to have his murder conviction overturned due to alleged prosecutorial misconduct.

Glossip, who has been on death row for more than 25 years, has asked the justices to grant him a new trial after the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals upheld his conviction despite recently uncovered evidence that could potentially help his defense. He accused the prosecutors who sought his conviction of withholding that evidence and the attorney general acknowledged the error.

Lawyers for Republican Attorney General Gentner Drummond and Glossip, in part, argued before the justices that Glossip's due process rights had been violated. Because Oklahoma's attorney general decided to support Glossip's appeal, the Supreme Court appointed an outside lawyer — private attorney Christopher Michel — to argue on behalf of the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals that Glossip's conviction should be upheld.

For nearly two hours, the justices pelted lawyers with questions concerning whether information from prosecutors' notes about the key witness whose testimony bolstered Glossip's conviction could have been enough to sway the jury twenty years ago. Much of the hearing also saw them wrestling with the appellate court's refusal to waive a procedural limitation on post-conviction relief in Oklahoma state, while they, at times, also grappled with whether the Supreme Court should even be deciding this case at all.

Austin Sarat, a Salon contributor and Amherst College professor of law and political science whose research focuses on the death penalty, argued that the proceedings fell short of delivering the revelations of "justices' interest in profound moral and legal questions" that are typical in Supreme Court oral argument.

"The court got bogged down in a variety of legal minutiae and legal technicalities," he told Salon in a phone interview, asserting that the focus of the proceedings "should have been on what [Glossip and Drummond] were arguing, which is, there was prosecutorial misconduct in the case."

While the justices weigh whether Oklahoma can execute Glossip despite those errors, "the question in the background is: Is it possible that Richard Glossip actually is innocent of the crime for which he was convicted? And if so, would the Constitution bar the execution of an innocent person?" Sarat added.

Glossip, now 61, was convicted of arranging the murder of his boss, Barry Van Treese, who owned a motel in Oklahoma City where Glossip worked as a manager. According to Reuters, all parties in the case agree that Van Treese was beaten to death with a baseball bat by motel maintenance worker Justin Sneed. Sneed confessed to the murder and accepted a plea deal that allowed him to escape capital punishment and involved testifying that Glossip had paid him $10,000 to kill Van Treese.

"The law is so interested in procedural niceties and procedural complexities that it loses really what's at stake in the case."

Glossip's conviction relied on the testimony and credibility of Sneed, who had a methamphetamine addiction and was receiving psychiatric treatment for previously undiagnosed bipolar disorder. Glossip had admitted to assisting Sneed in covering up the murder but denied being in on the plan.

Glossip's lawyers contend they were never informed about Sneed receiving psychiatric treatment immediately following his arrest and that prosecutors failed to correct a false statement Sneed made at trial about ever having received such treatment.

Alexis Hoag-Fordjour, a Brooklyn Law School professor who specializes in capital punishment argued that, given the defendants' differing sentences, an outcome where Glossip is executed "would fly in the face" of justice.

"How can the public trust the justice system where the person that carries out a murder is not given the death penalty, and the person that maybe participated — that participated in some aspect of planning if we're going to even agree with that argument — does get the death penalty?" she told Salon in a phone interview.

Hoag-Fordjour also noted some Americans' frustration with the fact that the federal appeals process requires the Supreme Court to determine if, in making its decision, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals fulfilled the requirements of due process, not to reexamine the events of the trial.

"The real focus then becomes did Oklahoma state courts get it right? Did the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals — was their decision based on adequate and independent state law grounds?" she said. "If so, then federal courts shouldn't disturb that ruling, and that can just feel removed."

We need your help to stay independent

Former U.S. Solicitor General Seth Waxman, who represented Glossip, told the justices Wednesday that Glossip had been "convicted on the word of one man" and had his due process rights violated as a result.

"[Sneed] lied to the jury about his history of psychiatric treatment, including the fact that a prison psychiatrist prescribed lithium to treat his previously undiagnosed bipolar disorder," Waxman said, adding: "The prosecution suppressed that evidence and then failed to correct Mr. Sneed's perjured denial."

Michel, who represented the Oklahoma court, challenged the claim that the newly disclosed information undermined Sneed's credibility or the prosecution's handling of the case. He also argued that the justices should defer to the Oklahoma court's ruling upholding Glossip's conviction based on the state's procedural bar limiting post-conviction legal efforts.

That bar was central to Wednesday's hearing and consumed much of the justices' questioning as they probed the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals' refusal to waive it. The Oklahoma attorney general had sought to have that limit waived in order to evaluate the merits of Glossip's underlying claims of misconduct, but the lower court prohibited him from doing so — a move several of the justices noted was unusual for the state given its usual practice.

Sarat said that the court's focus on the legal technicalities during Wednesday's proceedings — rather than on the man whose life is on the line — was "in moments bizarre and quite Kafkaesque, something out of an absurd story where the law is so interested in procedural niceties and procedural complexities that it loses really what's at stake in the case."

The three liberal justices appeared sympathetic to Glossip's cause, with Justice Sonia Sotomayor seeming most interested in directly addressing the merits of the case before them: the claims of federal due process violations.

Glossip's lawyers argue that the prosecutors' conduct violated two Supreme Court decisions pertaining to due process, Brady v. Maryland and Napue v. Illinois. The former holds that prosecutors must turn over all evidence, while the latter establishes that prosecutors failing to correct a witness' false testimony when they are aware it is false violates the defendant's 14th Amendment right to due process.

Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas seemed most skeptical of Glossip's claims of prosecutorial misconduct, while the positions of the remaining members of the court's conservative flank, who largely remained quiet during argument, seemed far more unclear, Hoag-Fordjour said.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, however, questioned Michel's argument that the knowledge that Sneed had bipolar disorder and lied on the stand wouldn't have influenced the jury's decision.

"I'm having some trouble on that last piece of the argument, if we get there, understanding that, when the whole case depended on his credibility," Kavanaugh told Michel before asking him to explain further.

Kagan also appeared to take umbrage with Michel's claim.

"If I know that he has gotten up to the stand and lied about anything, whether it's important or not — it might have been important; it might not have been important — if he's lying, if he's trying to cover up something about his own behavior, I'm going to take that into account in deciding whether, when he accuses the defendant, he's telling the truth," she told Michel, describing her perspective if she were a juror.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Chief Justice John Roberts earlier in the proceedings appeared to have come to the opposite conclusion, telling Waxman that the jury was aware during trial that Sneed was taking lithium.

"What they didn't know is that it was prescribed by a psychiatrist. Do you really think it would make that much difference to the jury?" Roberts asked.

Only eight of the justices heard arguments during Wednesday's hearing. Justice Neil Gorsuch recused himself reportedly because he was involved in a prior ruling in the Glossip case while serving on a lower, appellate court that heard cases from Oklahoma.

"There's a potential for an even split, which would ultimately mean that the lower court decision stands," Hoag-Fordjour said, "affirming or upholding the death sentence and the conviction. So, this actually requires a 5-3 decision, and it's unclear if Glossip will be able to secure five votes."

Liberal Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson floated the idea of sending the case back to a lower court to further evaluate whether the newly disclosed evidence favors Glossip's defense — a move all three parties opposed.

Her suggestion offered the justices a middle-ground means of deciding the case 5-3, allowing them to avoid both denying Glossip's claims and request for a new trial and completely affirming the Oklahoma appellate court's ruling, Hoag-Fordjour and Sarat said.

Wednesday's hearing was not the first time Glossip had come before the Supreme Court. The court has previously intervened to halt his execution twice — once last year before it took up his latest petition — and in 2015 the defendant unsuccessfully challenged Oklahoma's method of execution. Glossip has evaded execution nine times and eaten his "last meal" three times, according to CBS News.

He found an unusual backer in Oklahoma's Republican attorney general, who concluded after an independent investigation that prosecutors hid evidence that might have led to an acquittal. Drummond has said he believes Glossip's role in covering up Van Treese's murder at least makes him an "accessory after the fact," which would justify a lengthy prison sentence. But Glossip's murder conviction, he said according to Reuters, was too flawed for him to support.

For Sarat and Hoag-Fordjour, Glossip's case rings eerily similar to that of Marcellus Williams, a Missouri man who was convicted of murder, sentenced to death and executed last month after several eleventh-hour appeals for clemency and stays on his execution failed.

Williams, who was on death row for 23 years, had earlier this year received the support of the original prosecuting office that sought his conviction after it learned of potential prosecutorial misconduct in the case and trial two decades prior. The St. Louis County prosecuting attorney sought to reduce his sentence to life without parole but was ultimately unsuccessful.

Hoag-Fordjour said she hopes that, no matter what the justices ultimately decide, the case continues to encourage the public to question and withdraw support for the death penalty while moving "us closer, as a society, to the abolition of capital punishment."

Sarat added that increased public disapproval of the death penalty would be "the catch" of the Glossip case should the Supreme Court decide to uphold his conviction and death sentence.

"If the Supreme Court decides against him — it would be a tragedy for him and for every person in this country who cares about the constitutional guarantee of due process of law," he said. "But as is true in the Marcellus Williams case, in the end, the more the Supreme Court allows these very problematic cases to result in an execution, the more it fuels doubts about whether this country should continue to sentence people to death and execute people."

Read more

about the death penalty in the U.S.

Shares