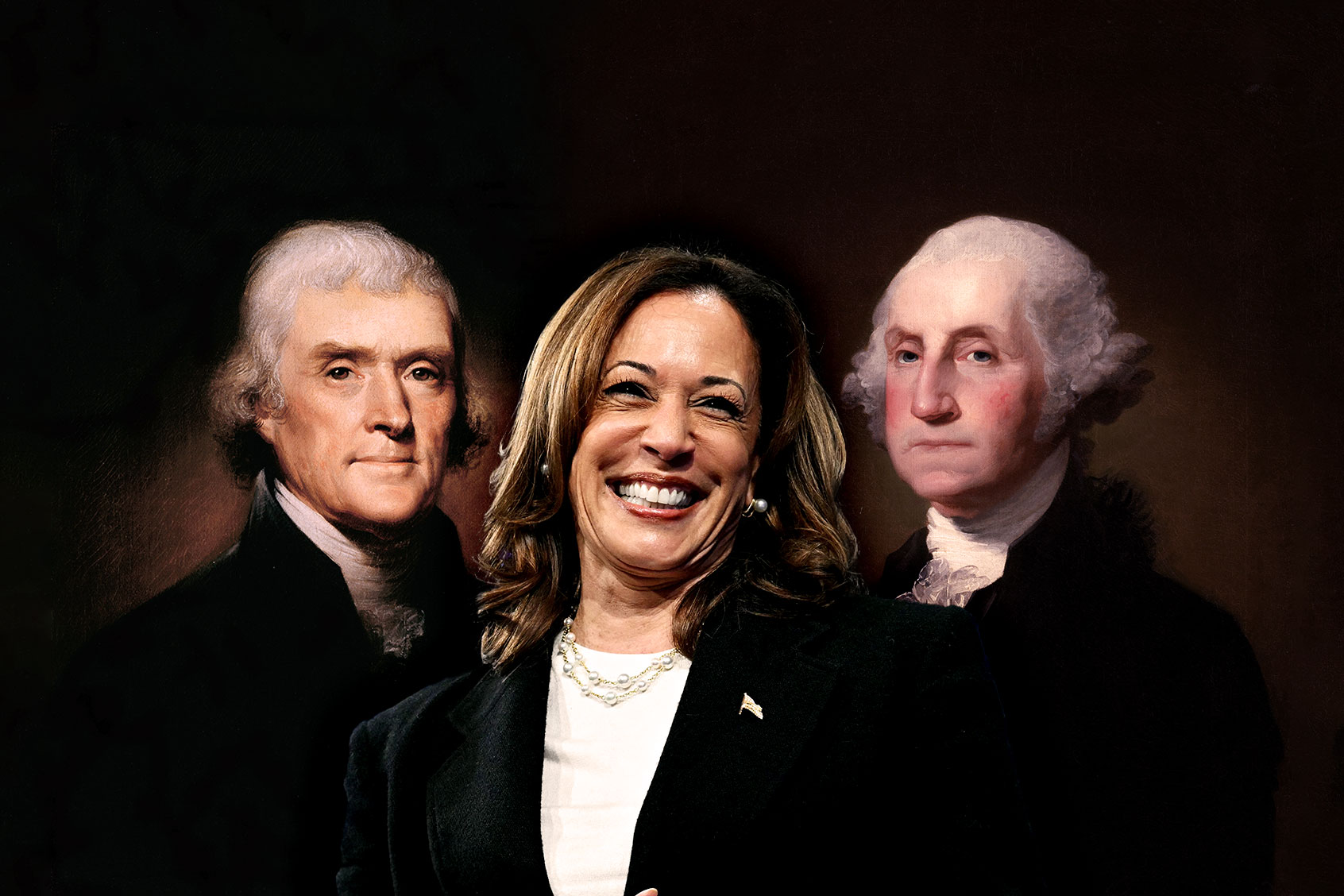

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Garry Wills got the obvious out of the way when asked about what America's founding fathers would have thought of the presidential election between former president Donald Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris. "Since women had no political position in the eighteenth century, I could not place this debate there," Wills told Salon.

Indeed. America's founding fathers operated in a strictly white supremacist, patriarchal world and therefore would have opposed Harris' campaign simply because she is a Black woman of Indian descent. Her marriage to a Jewish man would not have helped.

"Jefferson would have been horrified by Project 2025's backward-looking attitudes as obscurantist, antiprogress, and no friend of a pro-capitalist social agenda which Jefferson supported (if not without reservations in the manner of [Alexander] Hamilton)."

Yet despite these barriers of bigotry, in more than half a dozen interviews with top scholars of U.S. history, it turns out that the philosophical notions fueling the Harris presidential campaign are much closer to those of America's key thinkers than those of her opponent.

Such a conclusion may be shocking about a candidate whose party often claims to have a monopoly on respect for America's founding documents; it is much less surprising about a man who has said he would "terminate" the Constitution. Harris called Trump for his threats to democracy during the 2024 presidential debate, and both she and the moderators drew attention to how Trump violated Washington's precedent of peacefully relinquishing power in favor of election denialism and promises that he will make it so his supporters "won't have to vote anymore." As Harris astutely observed, Trump has clearly had "trouble processing" the objective reality that he lost to President Joe Biden in the 2020 election.

Similarly, when it comes to the objective realities of America's revolutionary history, the evidence shows that — to the extent that one can directly apply political philosophies from more than two centuries ago to the present — the founding fathers would have been far more likely to join the #KHive than wear MAGA red hats.

On scientific literacy

On key issue after key issue, the modern conservative community rejects established scientific fact. Scientists overwhelmingly agree that Earth's climate is warming to existentially dangerous levels because of human activity, primarily burning fossil fuels; the vaccines developed to fight COVID-19, such as the pioneering mRNA platform, succeeded in curbing a worldwide pandemic because the scientific community worked together; and gender theorists in both hard and social sciences confirm that transgender identities have a long history with a firm grounding in medical science.

Yet because the Republican Party's ideology cannot abide acknowledging the reality of anthropogenic global warming, successful mRNA vaccines and transgender identities, they instead encourage the general public to abhor both scientific literacy and the professionals who advance the frontiers of human knowledge. This is perhaps best embodied by Project 2025, the policy and personnel proposal book co-authored by more than 140 former Trump officials and introduced by his vice presidential running mate, Ohio Sen. J D Vance. In addition to pandering to the aforementioned anti-science prejudices — in some cases mixed with other prejudices, such as homophobia and transphobia — Project 2025 relies on the general public distrusting established scientists and refusing to comprehend the scientific method.

This would have "horrified" America's founding fathers. Many of them — from Benjamin Franklin to James Madison — were community scientists and argued that the government should be informed by scientific knowledge. For his part, Washington followed the leading doctors of his day when confronted with pandemics. Yet perhaps no founding father was as passionate about the sciences as the Declaration of Independence co-author and third president, Thomas Jefferson.

"Jefferson was alive in the early period of capitalism when its emergence from feudalism represented the economic aspect of the broad social emergence from feudalism," Dr. Richard D. Wolff, professor emeritus of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and author of "The Sickness is the System," told Salon. "That meant replacing medieval religion with 'modern' science religiosity, the new replacing the old, science as the vehicle for technical progress and thus ever more profit opportunities, etc. technical progress. Jefferson would have been horrified by Project 2025's backward-looking attitudes as obscurantist, antiprogress, and no friend of a pro-capitalist social agenda which Jefferson supported (if not without reservations in the manner of [Alexander] Hamilton)."

We need your help to stay independent

Dean Caivano, an assistant professor of political theory at Lehigh University and author of "A Politics of All: Thomas Jefferson and Radical Democracy," explained that Jefferson believed the American republic's future independence and sustainability depended on public education and science. "His 'empire of liberty' offered the potential to dismantle the artificial hierarchies inherited from the past and imbue all aspects of life with the promise of freedom and happiness," Caivano said. "Although this idealized image of a free and harmonious American society is undeniably marred by the institution and legacy of slavery, overlooking the role of education and science as prerequisites for freedom and equality diminishes our ability to assess the historical and contemporary limits of American democracy critically."

From Jefferson's optimistic point of view, America was already in the midst of a scientific revolution when its political revolution occurred, and he did not believe this to be coincidental. "Jefferson envisioned American science as an agent of transformation, reshaping all aspects of life—from units of measurement to farming practices and geological exploration," Caivano said. "According to Jefferson, creating an enlightened, scientific society was achievable by spreading accessible public education. Unsurprisingly, his founding of the University of Virginia is one of his most cherished personal accomplishments."

He added, "In contrast to Jefferson's vision, Project 2025—the ultra-conservative guidebook transparently designed to reshape the American federal government with a Machiavellian intent—relies on reactionary, draconian, and dogmatic thinking. By launching a direct assault on the scientific community, Project 2025 undermines the foundation of an enlightened citizenry that Jefferson held in high regard. The project advocates for dramatic cuts to research and development, promotes climate denialism, and seeks to hyper-politicize public health and STEM fields."

Columbia University historian Richard John, author of "Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse," detailed a list of Jeffersonian accomplishments that would have been impossible had he not placed such a high premium on scientific knowledge: the Lewis and Clark expedition across the American west, wariness toward broad patent protection, advocating public investments in science

"Jefferson was not a great fan of federal government regulation, but he would've supported state government regulation," John said. "The presumption that a scientific elite cannot or should not make decisions would have troubled Jefferson, although he would also have [hoped] that perhaps some of those activities could take place inside the individual states."

For his part Mark Peterson, a Yale University historian currently working on a book called "The Long Crisis of the Constitution," bluntly stated that "Jefferson would have been repulsed by Project 2025's rejection of scientific knowledge." While American University legal historian and Law & History Review editor-in-chief Guatham Rao suspects Jefferson may have liked the "anti-statist sensibility" in some of Project 2025's text, Rao agrees with the other scholars that Jefferson "would have found the idea of 'burrowing' into government to destroy it from within to be deeply dishonorable and ungentlemanly. And yes, he would not at all have liked the anti-scientific bent of it."

This is not to say that Jefferson's devotion to science was unlimited. In fact, when compared to some founding fathers who never became president (most notably Franklin), Jefferson was not even the most intellectually impressive of America's early leaders. Author Wills, who wrote "Inventing America: Jefferson's Declaration of Independence," pointed out to Salon that "Jefferson's was a deeply divided mind" on many issues, from the necessary strength of the federal government to whether he was more loyal to Virginia or the newly-formed United States. Yet even in his parochialism, Jefferson's broad-mindedness remained apparent.

"He knew that Dr. Witherspoon's College of New Jersey (proto-Princeton), attended by Madison, was superior to his own alma mater, William and Mary, and he established the University of Virginia, to compete," Wills said. "In the same way, he left Virginia and went to the enlightened and cosmopolitan Philadelphia to get vaccinated. The clash between his native and his aspirational ideals was never resolved Despite his own weather records kept at Monticello, little science got down on plantations. He went to the presidency thinking to preserve his first values, but international duties (especially for the navy) forced him to become, begrudgingly, a national leader."

On freedom of religion

If there is another regular theme to modern Republicanism, it is the notion that America is a "Christian" nation and should craft its policies accordingly. Even if one ignores the massive doses of Christian nationalist ideology infused into Project 2025, both Trump and his followers cite their religion as the basis for policies on issues ranging from public education and LGBT rights to abortion and race relations.

Not surprisingly Jefferson — who advocated keeping religion out of government for so long that he literally coined the phrase "wall of separation between church and state" — adamantly believed the government should be as secular as possible. Yet as with his enthusiasm for science, Jefferson was far from alone among the founding fathers in that respect.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

"The idea that you could have a Christian nationalist position would have just set Jefferson into paroxysms of rage," John said. "There was in fact kind of a Christian consensus, or the states having religious establishments. The religious establishment in Virginia had been abolished by James Madison. Massachusetts still had a religious establishment […] until 1833. The Jeffersonian party in Massachusetts never opposed the religious establishment in Massachusetts because it was popular [as it was not in Virginia—which helps explain why the religious establishment was abolished in Virginia so quickly]. [But almost no one favored a] federal mandate for religion." For example, when Jefferson's Democratic-Republicans (led by President Madison) passed an 1810 federal law requiring the mail to be open every day it was delivered, so-called Sabbatarians rose up to oppose this on the grounds that government officials should not work on a religious day, Sunday. From the Jeffersonian perspective, it was anathema to argue that government mail should not move to honor religious sensibilities, so they lost that battle.

"Jefferson was as remote from the idea of Christian nationalism as possible," Peterson said. "Washington? Over the course of his life, he didn't really have a great deal in the way of expression about religion. He does interestingly, on his national tour after he assumes the presidency, visits the Touro Synagogue in Rhode Island,, in Newport, to show his respect for the validity and importance of religious worship of all kinds." During that visit, Washington famously told the assembled congregants that he hoped "the Children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other Inhabitants; while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and figtree, and there shall be none to make him afraid."

As evidenced by Washington's kindness toward the Jewish community and the federal government's willingness to let states take their time easing out their religious establishments, the founding fathers were not hostile to the practice of organized religion. Jefferson even tried to rewrite the New Testament, albeit stripped of supernatural elements so that Jesus Christ would be a secular philosopher. Their position was nuanced — religion had its place, but that role should never mix with the one played by the government.

"People who we call the founders or whatever saw religion broadly defined as a vital element in the promotion of good citizenship, law-abiding, public mindedness," Peterson said. "It was a great nurturer of the kinds of values that you needed in a republic. But the idea that one religion or group of religions in particular should be 'that of the United States,' that was far from the minds of national leaders, in part because they all knew that the 13 former colonies that became states were just wildly different in terms of their religious commitments. The New England colonies had, except for Rhode Island, established religions as the sort of descendants of the Puritans' congregational Protestantism, while the southern colonies like Virginia and South Carolina had established the Church of England." Meanwhile Virginia operated under the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, authored by Jefferson himself and passed by the colony in 1786, which was intended as the template for the federal government's approach to religious matters. It emphasized that people could not be compelled to attend church, pay taxes to religious organizations or in any way face harm to their body or property because of their religious beliefs.

The founding fathers were far from perfect in practicing their secular beliefs. As alluded to earlier, in 1815 Secretary of State James Monroe infamously recalled a Jewish ambassador to the Kingdom of Tunis named Mordecai Manuel Noah in part on the grounds that his religion was “an obstacle to the exercise of [his] Consular function.” (Madison later retracted the religious explanation for Noah's firing and emphasized other reasons for the termination.) Yet even if the founding fathers imperfectly practiced separating church and state, they consistently preached it. Without question, they felt that "the First Amendment's rejection of the idea that Congress would establish any religion was in many ways a practical thing of these people knowing that there was no one religion that you could establish for the United States, and therefore the national government should keep its hands off of it," Peterson said.

On free speech

Twitter/X CEO Elon Musk openly spreads misinformation on the platform he purchased with the goal of electing Trump and furthering various right-wing causes. Meanwhile, TikTok, which is owned by China, has sent shockwaves through Washington over its potential use as a spying tool. The founding fathers, John notes, had a special interest in guaranteeing Americans' access to accurate information — and were worried that foreign bad actors would attempt to dupe the public.

These concerns came to the fore when Washington proposed, and ultimately passed, his signature Post Office Act, which established the United States Postal Service. "The Post Office Act 1792 was contested," John explained. "Washington had a radical position that was not adopted. He wanted all newspapers in the mail made free of charge. It was a radical position. And that would've been calamitous from the point of view of the postmaster general, who has an obligation to break even. [Washington was opposed by more conservative, or let's say less expansive-minded, Federalists who wanted [to admit] only the government [-sponsored] newspaper in the mail. That was what Madison opposed."

Ultimately the lawmakers compromised, with every American-originated newspaper being admitted in the mail at a low rate.

"Newspapers [were] by far the most important source of information on public affairs," John said. "Soon they become 95% of the weight of the mail, and they never pay more than 15% of their revenue. So [lawmakers supported] a massive government subsidy for newspapers—[to facilitate the circulation of] information on public affairs. [It is not too much to say that this policy could be understood as a precedent for the federal funding of election expenses.]"

Needless to say, this leads to some obvious conclusions about how they would have viewed Twitter/X and TikTok.

"Today we have TikTok and we have social media originating all around the world," John said. "The founders would've been deeply troubled by foreign interference with American politics." When asked specifically about the South Africa-born Musk and the circles in which the billionaire runs, John said that "Washington would've been troubled by foreign powers trying to undermine the sanctity of American elections by interfering with or by buying up or shaping editorial opinion. And of course, the Russians and Trump, this would have been seen as treasonous, straight up."

Elaborating on that last point, John pointed out that "Trump appears to have very close connections with the Russian government, and we've just learned maybe with the Egyptian government, and that would've been an anathema to Washington and Jefferson. They would have regarded [his ties with foreign leaders] as a cause for impeachment."

Perhaps the most astute analysis of the bottom line on Musk was summed up by University of Pennsylvania climate scientist Michael E. Mann, who has both written about and been victimized by misinformation on platforms like Twitter/X.

"Harris’ call for price controls, reminiscent of the Jeffersonian intervention approach, is politically astute."

"Elon Musk obviously bought Twitter with the intent to destroy it, to weaponize it for bad actors who helped fund his takeover, which includes Saudi Arabia and Russia," Mann said. "Twitter has become a cesspool for the promotion of misinformation and disinformation; Elon Musk is not an honest actor. By some measures, he has engaged in criminal behavior, and I think it's pretty clear that he has to be reined in and we are going to need much tougher regulatory policies to deal with companies like Twitter and Facebook, that are effectively monopolies now."

On policy

When Harris proposed a ban on grocery price gouging, supporters and critics alike compared her bold move to a policy passed by President Richard Nixon in 1971, like Nixon's price freeze and other liberal economic policies. Still Republicans like Trump insist Harris' every progressive economic program is a literal step toward communism. Yet according to the experts who spoke to Salon, Harris' policies are similar to those that the founding fathers would have contemplated.

"Early Americans were pretty well acquainted with radical market measures in times of crisis," Rao said. "Price controls were implemented in multiple jurisdictions during the American Revolution, though they differed pretty radically from place to place. The Continental Congress imposed price controls in 1775 and 1776. Given this background, it is likely some subset of founders would not object to price controls."

Once America won the Revolutionary War and became its own nation, it found that it needed even stronger centralized economic policies than previously expected.

"Washington had to forge the federal army by controlling and ultimately absorbing the state militias," Wills said. "In the same way, he had to forge the federal government by reducing the power of state taxing and financing, which could not have supported the Congress, the Supreme Court, and the armed forces. He promoted [Alexander] Hamilton's schemes for making this a national economy."

Caivano elaborated on Washington's various interventionist economic policies, including a number of legislative and executive measures that were initially very unpopular because they seemed to run athwart the notion of a government with limited power. While founding fathers like Federalist Papers co-author and Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton were not fazed by claims the state had acquired too much power, others disagreed with him.

"Reflecting on the prevailing ideas of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 and the formidable influence of Alexander Hamilton, Washington's presidency played a pivotal role in solidifying the mechanisms of the American nation-state and embedding government interventions into the economy," Caivano said. "More conservative than Jefferson, Washington's brand of republicanism promoted an exclusionary nationalism, a strain of thought that has persisted throughout the republic’s history and has been strongly embraced by Trump. Washington's broad political vision would significantly transform economic policy, from taxation to establishing the National Bank to suppressing the Whiskey Rebellion and implementing protective tariffs."

The net effect of Washington's policies, which were economically nationalistic and state-centered, was a stronger federal government with expanded state power supported by the new Constitution, Caivano explained.

"Vice President Harris follows this tradition, advocating for federal government intervention in economic matters to maximize positive social outcomes," Caivano said. "Harris has called for direct investments in green technologies, infrastructure, and workforce development. What sets her proposals apart from a purely Hamiltonian approach is that modern liberalism attempts to blend economic benefits with efforts to address preexisting social inequalities. This results in Democrats, including Harris, engaging in strategic messaging tailored to different audiences. It has become common for Democrats to praise neoliberal economic policies to venture capitalists and Silicon Valley elites while simultaneously proposing solutions to issues like systemic racism, transphobia, and white supremacy to community leaders. The debate over governmental intervention in economic terms is a distraction, as such intervention is essential for the continued accumulation of economic inequality."

As America's first president, Washington was naturally the first founding father to be accused of meddling with the economy — but he was not the last. According to John, Jefferson was accused of "draconian" interventions when he passed the Embargo Act of 1807. Exhausted with the British Empire impressing American sailors into military service and refusing to accept United States neutrality in its conflict with France, Jefferson imposed a general trade embargo that crippled the New England economy.

"Jefferson was willing to shut down commerce in 1807 entirely to prevent a foreign war. He wanted low tariffs," Wills said. "We're talking about shutting down commerce—[a major industry for an entire region—that is, New England]. That's pretty draconian. Jefferson shutting down seaboard commerce led New Englanders to seriously talk about seceding from the union."

While Jefferson's contemporary critics blasted him for seemingly abandoning republican principles, Caivano told Salon that his policies "upheld key tenets of liberalism." At the same time, he was also a pragmatist, one who realized some of his doctrines would need to give way as circumstances evolved.

"While in office, he frequently departed from pure liberal thought, operating less as a steward of power and more as an assertive executive," Caivano said. "Confronted with opposition from Federalists and New England town halls, Jefferson did not hesitate to bypass the liberal principles of a restrained executive, as evidenced by his purchase of Louisiana from France and his signing of the Embargo Act of 1807. These instances reveal an alternative aspect of Jefferson’s liberal worldview: pragmatic responsiveness shaped by circumstances, with justifications often framed with economic terms. Jefferson’s public rationale for acquiring Louisiana or prohibiting American trade in foreign ports was centered on safeguarding American interests, both politically and economically. These decisions, which Jefferson argued would benefit America in the short and long term, were more calculated and politically motivated than those of a strict adherent to liberalism, highlighting the nuanced nature of political decision-making."

He added, "Harris’ call for price controls, reminiscent of the Jeffersonian intervention approach, is politically astute. Despite the low likelihood of implementation, Harris appears to be banking on the perception of decisive leadership rather than the proposal's feasibility. Bold, sweeping proposals, especially when they provoke outrage among Fox News-driven ideologues, generate significant attention. However, in the conservative arena of hyperreal discursive discourse, the lack of discussion about the federal government’s current engagement in price controls on fossil fuels is notable. While the practicality of Harris’s proposal may be debatable, its political shrewdness is undeniable. The Founders, from Washington to Jefferson, would likely publicly denounce such a move while privately acknowledging its merits."

Wolff was even more optimistic; he suspected the founding fathers may not have even been private in their support for the Harris economic agenda.

"The more democratic founding fathers (Jefferson, [political philosopher] Sam Adams, Patrick Henry) would have supported Nixon in 1971 and Harris in 2025 for 2 key reasons," Wolff said. "[First], inflation hurts prices-setters (employers) less than price-takers (employees) most of the time, and [second] wage-price controls favor the rich less than raising interest rates. The less democratic founding fathers would have been less likely to supporty Nixon's actons in 1971 or what Harris would do if she were to follow Nixon rather than the more recent Democratic and Republican Federal Reserve leaderships."

On the economy

Despite the glossy rhetoric of politicians from both parties, the founding fathers were not angels or even particularly god-like. They were flesh-and-blood human beings, fallible like all of us, and nowhere were these imperfections more apparent than in their obeisance to neoliberalism — that is, free-market capitalism. Indeed, when it came to capitalism's tendency to benefit the wealthy, the founding fathers were quite pleased with the result. In this respect, one could easily connect their views to those of the Republican presidential candidate.

"Trump's economic approach has much more in common with founders era political economy because of shared protectionism and elitism," Rao said. "While the Federalists use of tariffs was chiefly for revenue, Jefferson saw some protectionist rationale in market restrictions, especially his embargo policy. James Madison followed suit with his non-intercourse law. Harris' interest in the middle class and social safety net was completely foreign to early American economic thought. It was not until the late 19th century that these became mainstream ideas."

Similarly, because both politicians are pandering to constituencies within the paradigm of America's two-party system, each ultimately reinforces the social and economic status quo while proposing reforms to benefit specific interest groups.

"What stands out in the agendas of both Harris and Trump is that while they claim to advance ideological purity—progress, innovation, and personal liberty on the one hand versus protectionism, exceptionalism, and racial homogenization on the other—both are ultimately entrenched in a neoliberal framework," Caivano said. "Neither Harris nor Trump accurately embodies the philosophical principles of liberalism or conservatism. Instead, they offer a blend of ideologically curated points meticulously crafted to resonate with specific demographics, including supporters, donors, and economic interests. Their policy proposals—from tax cuts and heightened tariffs to investments in green technologies—depend on societal relevance, resulting in governance platforms that often lack consistency and, at times, appear contradictory but remain primarily unattainable."

We need your help to stay independent

Necessarily, this article must close by repeating a point made near the beginning — that because the founding fathers lived in the late 18th and early-19th centuries, their ideas can only be loosely applied to the conditions of 2024.

This is why Brown University historian Gordon S. Wood, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning "The Radicalism of the American Revolution," told Salon that "I don’t think Washington-Hamilton and Jefferson can be easily compared to the present candidates." He noted that Washington and Hamilton wanted "a fiscal-military state with a large standing army and navy in emulation of Great Britain. They were suspicious of democracy, Jefferson was utterly democratic by 18th-century standards and was essentially a libertarian believing that the federal government should have no role whatsoever in the economy. Not much you can make of that to fit present circumstances… I don't think anyone can say what Washington would think about someone or something in our present."

On the other hand, Caivano told Salon that both Harris and Trump "operate within the ideological framework inherited from the early American republic" in the sense that they are philosophically malleable. From Washington, Hamilton and Jefferson to Trump and Harris, all of these American leaders were first and foremost political creatures.

"This binary of Jefferson versus Hamilton, agrarianism versus commercialism, is woven into America's political fabric: red or blue, liberal or conservative," Caivano said. "Yet, what is essential to understand is that the positions of Jefferson, [President John] Adams, and even Hamilton were not static. Their ideological stances evolved, revealing that the American political imagination is less about strict philosophical adherence and more about political flexibility to advance a social order that fundamentally supports a patrician form of governance. Both Jefferson and Hamilton, at different times, promoted the proliferation of the manufacturing sector and the importance of international trade and American financialization. The critical takeaway from examining the early republic is that rhetoric framing adversarial relationships with rivals often garners more political capital—and, consequently, more votes (and financial backers)—than strict adherence to assumed ideological principles."

Read more

about this topic