Turns throughout PBS' “Leonardo da Vinci” remind us of how similar his era was to ours. Da Vinci’s Renaissance was a time of doubt and great uncertainty. His native city of Florence, Italy, was an oligarchy shaped by wealthy families, including that of Cossimo de Medici, a generous patron of the arts under whom an artistic class thrived.

The self-taught genius rode waves of political and cultural transformation by forging connections to other well-heeled, expansive intellects. Still, he wasn’t above aligning himself with strongmen if the price was right. When he wasn’t working on masterpieces that would endure for centuries, he was inventing weapons, schematics and maps for Cesare Borgia and offering his services to other city-states’ rulers.

"He is the embodiment of what it means to be fully alive, and aware, and questioning everything."

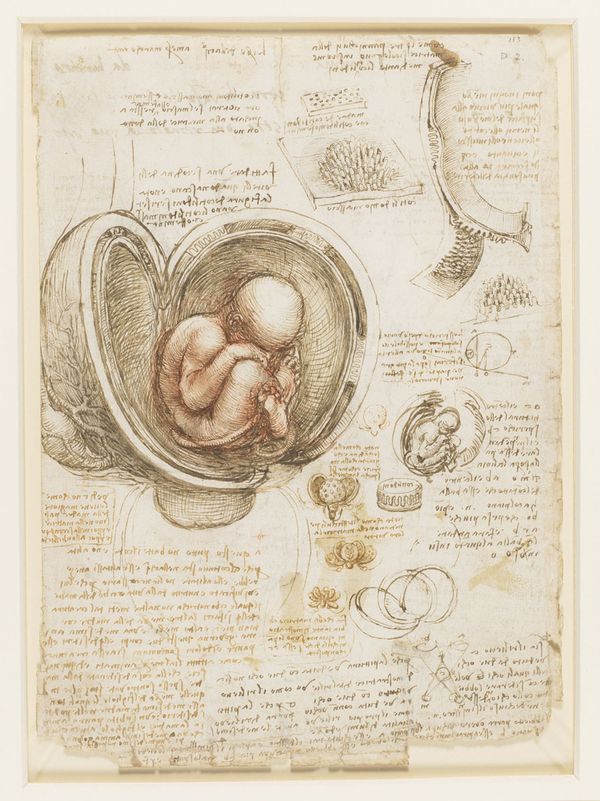

When a religious zealot came to power in his native Florence and inspired mass burnings of portraits, carnival masks, mirrors, perfumes and other vanity objects, da Vinci leaned into architectural designs. His later years yielded some of the most important early drawings of human physiology along with discoveries that revolutionized medicine.

The four-hour “Leonardo da Vinci,” directed by Ken Burns, Sarah Burns and David McMahon, represents Burns’ first documentary profile of a non-American subject. In its way, though, it snugly fits into the filmmakers’ exploration of the American story.

Biographer and journalist Walter Isaacson recognized that when he recommended that the Burnses and McMahon guide viewers through da Vinci’s storied life and accomplishments. So do the varied personalities who speak to his multidisciplinary inventiveness, a roster that includes engineers, historians, writers and director Guillermo Del Toro.

Every would-be innovator – are we still calling them disruptors? — aims to be the da Vinci whether or not they acknowledge that to be the case. Few if any qualify as true polymaths as the Renaissance artist personified the term, and without the benefit of a traditional education. Only legitimate family heirs could attend universities in his time, and da Vinci was born outside of wedlock.

Had he received an heir’s formal schooling, da Vinci would likely have become a notary. Instead, he learned through observing the world around him, inspired by nature and the artistry of calculation. “Nature begins with the cause and ends in experience,” he wrote.

Fetus in Utero by Leonardo da Vinci (Courtesy of PBS/CreditRoyal Collection Trust/© His Majesty King Charles III, 2024/Bridgeman Images)Da Vinci's way of processing the world ensured he'd transcend the designation of acclaimed painter, sketch artist and sculptor. His work cemented his status as an engineer, scientist and theorist whose findings are instructive centuries after he lived.

Fetus in Utero by Leonardo da Vinci (Courtesy of PBS/CreditRoyal Collection Trust/© His Majesty King Charles III, 2024/Bridgeman Images)Da Vinci's way of processing the world ensured he'd transcend the designation of acclaimed painter, sketch artist and sculptor. His work cemented his status as an engineer, scientist and theorist whose findings are instructive centuries after he lived.

“He is the embodiment of what it means to be fully alive, and aware, and questioning everything,” Ken Burns said to TV journalists covering PBS’ presentation at the Television Critics Association’s press tour in July.

"Leonardo da Vinci" emulates his way of seeing the world, making it a departure from Burns’ other work.

But please resist the impulse to liken him to certain tech bro dropouts. Although his vast body of work is populated by many unfinished pieces, as one expert explains, this is because the questions he sets for himself cannot be easily answered. Translation: he thought in vast terms but recognized that materializing certain concepts was beyond the scope of what he could do or wanted to do.

Such thinking didn’t get in the way of the director realizing da Vinci’s story in a way that captures his essence and captivates the audience. An observation by writer and essayist Serge Bramly sums up the philosophy fueling the four-hour, two-part documentary’s execution: “Leonardo was himself a work of art even before creating art,” Bramly says.

We need your help to stay independent

He was referring to the way da Vinci looked, dressed and appeared in paintings, whether created by others or self-portraits. It also suits the stunning whirl of animation presented side-by-side with the artist’s work and writings, interwoven with footage of human expressions, features, interviews and narration. Before telling the story of its polymath, “Leonardo da Vinci” emulates his way of seeing the world, making it a departure from Burns’ other work.

Its singular style can be attributed in part to necessity. “One of the reasons we were attracted to the film was because of the challenge of how we might visually capture who he was,” McMahon told critics in July. “We weren't going to have the archives. We weren't going to have the photos or the film.”

Not only that, as Sarah Burns cited, the historic record of da Vinci’s life and that of most artists was thin at best. “While Leonardo left behind many thousands of pages of his notebook entries, which provides us with this amazing way to get inside his head, he very rarely writes about his personal life, his feelings about things. It’s always what he’s thinking about,” she said.

Burns was referring to the limited records confirming da Vinci’s sexual orientation. (The film cites a legal document linking him to a scandal involving a friend accused of engaging in homosexual acts and his lifelong companionship with pupil Andrea Salaì to address that conversation.)

But this also describes the documentary’s means of imagining the mechanics of da Vinci’s logic and imaginative flights. McMahon explained that da Vinci’s deep consideration of nature and his view of art and science as indistinct from each other informed the filmmakers’ decision to put aside their tried-and-true cinematic conventions.

That detour yielded a work that stirs emotions through visuals alone. One can watch “Leonardo da Vinci” with the sound off and be mesmerized and, this is key, soothed. With the sound on we’re immersed in a tapestry of languages and Caroline Shaw’s diaphanous score, along with the classic Burnsian touch of Keith David’s narration interwoven with Italian actor Adriano Giannini’s readings of his journals.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

It’s as if the filmmakers were trying to create an intellectually nurturing rival to Calm app content: You can feel your anxieties melt away while watching “Leonardo da Vinci” while feeling reawakened and fully engaged. It might even recharge your faith in humankind.

The Virgin and Child by Leonardo Da Vinci (Courtesy of PBS/Musee du Louvre via Art Resource)The Renaissance birthed many modes of thinking; the same era that gave us da Vinci and his mononymous rival Michelangelo also yielded Niccolò Machiavelli whose work “The Prince” is still instructing power-hungry bros on how to get ahead by behaving like a f– former president.

The Virgin and Child by Leonardo Da Vinci (Courtesy of PBS/Musee du Louvre via Art Resource)The Renaissance birthed many modes of thinking; the same era that gave us da Vinci and his mononymous rival Michelangelo also yielded Niccolò Machiavelli whose work “The Prince” is still instructing power-hungry bros on how to get ahead by behaving like a f– former president.

In this dark, anti-Enlightenment hour of our nation’s history, Machiavelli’s philosophy may seem to have a broader relevance. His treatise was meant to educate the wealthy and powerful about the best means of outwitting each other and subjugating the working classes, and he correctly deduced that the peasants would never read it.

Among da Vinci’s earlier mechanical schematics were devices for removing bars from windows and opening a prison cell. We get to decide for ourselves which of those ideas is more inspiring.

"Leonardo da Vinci" airs in two parts at 8 p.m. on Monday, Nov. 18 and Tuesday, Nov. 19 on PBS member stations. Check your local listings.

Shares