In years to come, when we reflect on the legacy of Donald Trump’s second presidential term, it may well include perpetuating one of America’s most pervasive myths.

Minutes after taking his oath of office, Trump in a bombastic inaugural speech — more jingoistic battle cry than celebratory diplomatic remarks — declared that, henceforth, the U.S. would be a perfect meritocracy, with no need for diversity, equity and inclusion programs.

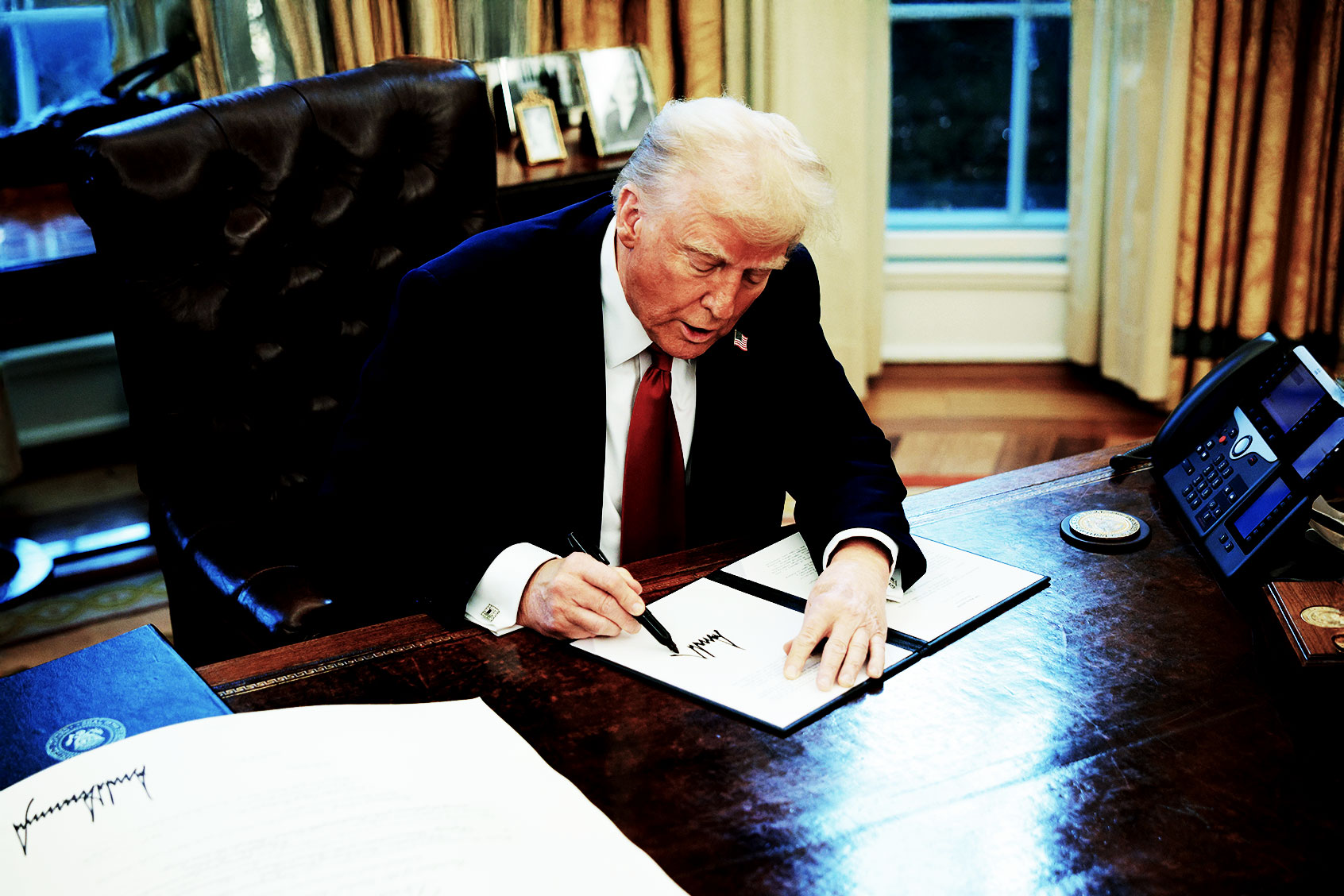

"I will […] end the government policy of trying to socially engineer race and gender into every aspect of public and private life," he boasted. "We will forge a society that is color blind and merit- based." He then signed several executive orders dismantling DEI programs across the federal government and encouraged the private sector to follow suit.

In the past, phrases like "color blind" and "merit-based" — though loaded, sometimes racist and certainly complex — have been used across the labor market, and frequently even with good intentions.

Many hiring managers, at least consciously, have believed that when they’ve made job offers and offered pay rises, they’ve done so to candidates who are the most qualified, skilled, knowledgeable and perhaps the hardest working. They’ve believed that those who are turned down are not rejected on the basis of their gender, sexuality, identity or race.

Decades of relying on the rules of an ostensible meritocracy, however, have proven one thing: that it's an illusory social ideal. Meritocracies don’t work. They exacerbate inequality. They make the rich — who in this country are already ludicrously wealthy — richer, the poor poorer, and they squeeze the marginalized even further out of the picture.

We need your help to stay independent

Self-validating merit

When Trump uttered the phrase "merit-based" during his inaugural speech, Michael Smets, a professor at the University of Oxford’s Saïd Business School in the U.K.—watching on TV from the other side of the Atlantic — flinched.

"I immediately thought to myself, 'But killing DEI programs actually undermines meritocracy,'" he said. Smets’ logic isn’t hard to follow. When we rely on meritocracies — when we tell ourselves that we’re capable of judging merit "objectively," whatever that might mean — bias and heuristics inevitably come into play.

In 2012, Lauren Rivera, a professor at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management, coined the term "looking glass merit" to describe the unconscious tendency that humans have to define merit in a way that is self-validating.

If a manager is told to hire, promote or offer a pay rise to someone who is "ambitious" or "driven," that manager will bestow that award on someone who resembles him or her. After all, don’t we all consider ourselves to be ambitious and driven?

And to be clear, being biased does not mean that someone is bad or malicious — it just means that someone is human, said Elaine Lin Hering, the author of Unlearning Silence, a book about how to recognize and unlearn unconscious patterns. "All humans have biases," she explained. And in addition to being wired to prefer people who are like us, we are also conditioned to believe that they pose less social threat because they feel more known to us, Hering says.

"Without concrete and consistent criteria, our biases color our perceptions of someone’s merit," she noted. "Even with criteria, men are often evaluated based on their perceived potential while women are evaluated on performance."

"Even with criteria, men are often evaluated based on their perceived potential while women are evaluated on performance"

Iris Bohnet, a behavioral economist and professor at the Harvard Kennedy School, said she knows of "more than 300 studies" that show that when employers screen identical resumes where only the name, age or religion of a job-seeker differ, there are substantial differences in the chances of getting an interview.

"That is the power of unconscious bias," said Bohnet, who co-wrote a book called "Make Work Fair" about redesigning the workplace using data. "So, unless we do something about stereotypical judgments and in-group bias, and the many other ways in which unfairness can undermine our workplaces, meritocracy indeed remains a myth."

And this is precisely what Smets is talking about.

But there’s also something even more basic that triggered his reaction. "I wonder how ‘meritocratic’ a $1 million gift from daddy is to get your business started?" he mused. "Not much meritocracy there."

A painful paradox

One particularly troubling piece of research on meritocracies shows that even the simple act of explicitly championing meritocracy as a core corporate value can promote discriminatory behavior — which can manifest in all kinds of ways, including promotion gaps and pay gaps.

In 2010, Emilio Castilla, a management scholar at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the sociologist Stephen Benard at Indiana University published their paper based on their studies of companies that tried to implement meritocratic practices, such as performance-based compensation.

Shockingly, they found that in companies in which meritocracy was openly espoused as a core value, men were paid less than women in cases in which both genders had identical performance review evaluations. When meritocracy was not explicitly promoted as a company value, the differences vanished.

"This finding demonstrates that the pursuit of meritocracy at the workplace may be more difficult than it first appears and that there may be unrecognized risks behind certain organizational efforts used to reward merit," the authors wrote.

Trump and his administration have already demonstrated that their mode of governing is to make bold, swashbuckling declarations — including on concepts like meritocracy. Trump’s team is also the richest ever to run the U.S. government. He has tapped at least 13 billionaires for jobs in his administration.

Meanwhile, a report recently published by the Congressional Budget Office shows that between 1979 and 2021, the average income of the richest 0.01% of households in the U.S. grew nearly 27 times as fast as the income of the bottom 20% of earners.

Separate research shows the richest U.S. cities are now almost seven times wealthier than the poorest regions — a disparity that has practically doubled since 1960.

In January 2012, the late economist Alan Krueger, who at the time was Barack Obama’s chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, laid out in a speech precisely why inequality in the U.S. is bad for everyone in the U.S., regardless of income.

It reduces productivity, spending and morale, and it weakens the middle class which in turn destabilizes markets, he explained. In other words, he concluded, "restoring more fairness to the economy would be good for all parts of American society." This is not,” he added, "a zero-sum game."

One might almost be tempted to say that making America fairer again could be the best way to make America great again. But making America merit-based again? What an utter tragedy that would be.

Read more

about this topic