“Have you ever heard the story of the gråkappan?”

“Severance” opens many passages into Lumon Industries’ cultish mythology, many of which begin with weird, sad stories. But there’s reason to suspect that some of them, including this lurch off-topic by the Severed floor’s department manager, Mr. Milchick (Tramell Tillman), are a misdirect — if not total bull.

Predictably, the answer is that no one on the Macrodata Refinement team has heard of . . . whatever it is he’s talking about, which he pronounces as glockSHOObin. Milchick launches into a fable of “ancient times” when the king of Sweden would disguise himself in an old gray robe and walk among his people to get a sense of their grievances. Kier Eagan himself was known to do so in his ether factories, Milchick says with delight.

“Severance” takes corporate dialect beyond the practice of concise, emotionally neutral workplace communication — office jargon’s alleged purpose — into an alternate universe.

Since this is all in the service of downplaying an extreme deception and physical violation, the MDR team rightly suspects this is entirely made up, as should the audience. The term gråkappan, as it appears in the script, translates to “gray coat,” a nickname for Charles XI, the Swedish king Milchick refers to. That part is based on reality. Everything else is suspect, down to the term’s pronunciation – which, Tillman told me during a recent conversation, he made up. “I was tasked with making the word sound as Swedish as possible,” he said, laughing at the memory of hearing the production crew laughing each time he said it.

But, as he explains, the correct pronunciation isn’t the real point. “I was like, if anybody could say this word correctly, it would be Milchick,” Tillman said, “because of course he knows this Swedish word.” That's because Milchick is a company man fluent in Lumon Industries’ distinct cultural jargon.

Corporate language is an aspect of work for which few can prepare. The patois changes from office to office and company to company, and the meanings behind certain terms shift from person to person. Some are overused to the point of resentment; how many aborted suggestions began with a manager assuring you he’d take that discussion offline, or circle back?

Others camouflage more sinister notions, like a company touting its eternal “start-up culture” ethos instead of warning potential employees that they expect 80-hour workweeks.

“People joke that when you get hired at Google, they have to give you a dictionary so you can understand all the terms,” advised Columbia Business School professor Adam Galinsky in his school’s publication. This sounds like life at Lumon.

The catch in all of this, Galinsky warns, is that this unifying means of speaking is as likely to create division between insiders and outsiders as it is to foster workplace cohesion — which also sounds like what working at Lumon is like, from what we've seen.

“Severance” takes corporate dialect beyond the practice of concise, emotionally neutral workplace communication — office jargon’s alleged purpose — into an alternate universe. Lumon's language is flowery yet extremely precise, as recently terminated long-timer Irving B. (John Turturro) once told his Macrodata Refinement co-workers Mark S. (Adam Scott) and Dylan G. (Zach Cherry). This is before Irving unmasks the person they thought was Helly R. (Britt Lower), but who turned out to be Helly’s “Outie” persona Helena Eagan, heir to the company, spying on their “Innies.”

Irving had his suspicions since MDR returned to work, but they come to a head when the team is dropped into an ORTBO — an Outdoor Retreat Team Building Occurrence — in a snowy forest where Irving threatens to drown Helly R. unless she reveals her true identity. Thus the verbal excursion to ye olde Sweden and Milchick's attempt to reframe Helena's hijacking of Helly R.'s identity as “carrying on [a] noble tradition.”

Perhaps by now you’ve picked up on the preposterousness in this parade of terms. The ORTBO acronym is as proprietary as the entire thinking behind a “severed” workforce. But the insider experience at Lumon is byzantine in other ways. Employees are encouraged to gain mastery over what Kier Eagan describes as the Four Tempers: Woe, Frolic, Dread and Malice. Controlling these “tempers” produces more effective workers and better people, so goes the theory. And Mark's work on "Cold Harbor," whatever its purpose, “is mysterious and important.”

Part of the MDR’s team ORTBO requires them to listen to a fable about the company founder Kier Eagan’s long-ago forest walk with his twin, who made a horrified Kier listen as he “spilled his lineage upon the soil” – a fancy way of describing masturbation. Hearing this read aloud at a work function isn't grounds for a conversation with HR but, rather, company lore that must be taken seriously. Since Helly/Helena laughs at the story, the team loses their "perk" of enjoying roasted marshmallows.

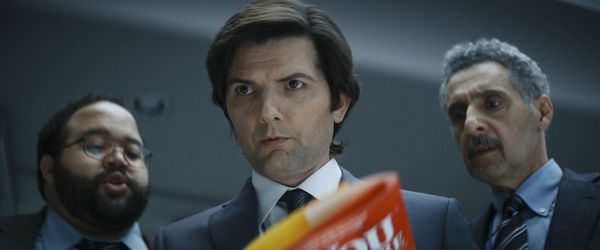

Tramell Tillman in "Severance" (Apple TV+)

Tramell Tillman in "Severance" (Apple TV+)

But let’s put a pin in all that for now to brave the forest maze that is “Severance” creator Dan Erickson’s thought process.

If we were to squeeze through small cracks in his mind’s cavern walls or crawl down its miniaturized hallways toward Erickson's nerve center, we might find ourselves in a room with a broken printer. This malfunctioning piece of office equipment is half symbol, half informative memory fragment starring in an anecdote he shared with me during a recent video chat about a job he had long before creating “Severance.”

Erickson remembers his team pleading with headquarters for months to send them a printer that worked. Instead, upper management sent a talking head who gave a two-hour motivational speech outlining the seven new corporate principles that the company’s executives cooked up during their recent weeklong “retreat” in Aruba.

“We were like, ‘Just give us a printer, man. Give us the things we need to do our jobs,” Erickson said, while also recognizing, as he put it, the note behind the note. “‘If you guys can't print, that's your fault. You should follow the corporate principles more rigorously, and then you would somehow be able to print even without a working printer.’”

Illogical as this reads, it’s also the story of modern corporate life – one that happens to resemble the inanimate villain in Mike Judge’s Gen X comedy classic “Office Space,” proving why the scene of its besieged workers beating it to death in a field remains famous. We've all been cheerily instructed to do more with less, often without basic tools.

We need your help to stay independent

Erickson, though, saw something far more sinister in that busted device than managerial ineptitude. He noticed the company’s top executives weaponizing language to control their employees.

“There's a lot of power in the way that we talk about things, but then that power can very much be co-opted,” Erickson observed, “and in a company like Lumon, where they require complete control over everybody,” language provides the means by which management can exert its will over employees’ bodies and minds, he added.

Jargon, he noticed, can be imbued with pseudo-religious significance. Taken far enough, he says, the guiding principles of the corporate handbook “starts to feel like a religion.”

“There's a lot of power in the way that we talk about things, but then that power can very much be co-opted,” Erickson observed.

This is a common enough practice for the viewer to recognize themselves in Mark S. and his colleagues in Macrodata Refinement, a team doing vital work that even they don’t entirely understand.

Our devotion to corporate jargon fuels enough inspirational business literature to cave in a library, most of which is useless, like the writings of Mark S.’s bumbling brother-in-law Ricken Hale. In the first season, Ricken’s nonsensical self-help book, “The You You Are,” somehow gets into the hands of Mark's “Innie” and sparks his yen for dissent. Since the world outside of Lumon is merely a concept its severed workers accept as fact, so are its ideas. The only literature they’re exposed to at work, besides that ORTBO apocryphal text, is “The Compliance Handbook,” the company’s book of commandments.

Zach Cherry, Adam Scott and John Turturro in "Severance" (Apple TV+)

Zach Cherry, Adam Scott and John Turturro in "Severance" (Apple TV+)

“The You You Are” is self-help hackery rife with fool’s gold like, “A society with festering workers cannot flourish, just as a man with rotting toes cannot skip” encrusting bumper sticker calls for rebellion. “Should you find yourself contorting to fit a system, dear reader,” one line advises, “stop and ask if it’s truly you that must change or the system.

To Mark, this is mindblowing. And Lumon can't abide severed minds to be expanded.

The fifth episode of Season 2 reveals Lumon is paying off Ricken to revise “The You You Are” to better align with Lumon’s mission and further exert control over its workforce.

“Your sovereign boss may own the clock that greets you from the wall,” writes Ricken in this revised draft, “but you get to enjoy its ticking, and thus should be happy.”

“I am just trying to speak their language,” Ricken explains to his wife Devon (Jen Tullock), who points out that it sounds like Lumon’s language.

“Well, it's a Trojan’s horse!” Ricken replies defensively. “If I can get my ideas to severed workers all across the world, it might beget a revolution.”

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

You can decide for yourself how realistic that is since Apple TV+ made eight ludicrous, Easter-egg-laden chapters of “The You You Are” available for download or an as audiobook. If you read that joke to the last page, though, you may notice how comparable Ricken’s nonsense gospel is to inspirational manuals adopted by real companies.

Any survivors of author-designed workshops will recognize malevolent verbal jiujitsu disguised as poetic advice on how to construct a non-apology ("I'm sorry if you feel that way") or coercion tactics like “win-win or no deal.”

Recognizing the nuances of the workplace's dialect is one task. Mastering elaborate phrasing, as Milchick has done, shows an aspiration to ascend the management ranks. Just as one of Lumon’s top officers, Mr. Drummond (Ólafur Darri Ólafsson), refers obliquely to Helly R.’s rebellion as a “contretemps,” as if to soften the implications of what she did, Milchick tries to comfort Dylan G. by assuring him that his fired colleague isn’t dead.

Irving's “outie,” Milchick says, has “departed on an elongated cruise voyage.”

Assaulting his co-worker got Irving B. fired, but understanding how corporate linguistics operates means knowing people are penalized for far less, sometimes for following corporate culture to the letter, as Milchick does.

Recognizing the nuances of the workplace's dialect is one task. Mastering elaborate phrasing, as Milchick has done, shows an aspiration to ascend the management ranks.

Through him, we see that fluency in a company’s manner of speech doesn’t guarantee the locals will accept you as one of their own. In Milchick’s first employee evaluation as department chief during "Trojan's Horse," Drummond takes him to task for “using too many big words.” As he tries to defend himself, Drummond silences him with, “Anti-deflections will be heard after the lunch break.

“His thoughts are getting too complex,” Erickson explains. “He's putting more nuance into his job than is needed or wanted, and by that point in the story, he's been making efforts to foster the humanity of the severed workers, misguided though they may have been.”

But the “Severance” creator reveals an ulterior motive in that confrontation. “I talked a lot with Tramell about his experiences working in past jobs, the very narrow path that he was expected to walk and what people expected him to be, you know, as a Black man in those settings — how fraught and painful that was,” Erickson said. “And so we wanted to do something that was in the language of the show that also felt true to those experiences and those issues.”

“The fact that Lumon is not able to accept this man and his vast vocabulary because it is anathema to who they think he is, and they’d rather control him in a whole other way, was really powerful,” Tillman said. “And I wish I could take credit for the idea, that Dan had to create this speech policing. But I can't. That was all his creation.”

Proof, you might say, that the people in charge of building the show’s world walked among us for long enough to understand how to communicate the oddity of making indirect, unnatural language the common tongue of workplace communication. After all, like Ricken says very plainly in “The You You Are,” “What separates man from machine is that machines cannot think for themselves.”

“Also,” he adds stupidly, “they are made of metal, whereas man is made of skin.” That, as we know, can be cloaked in shades of gray either with words or plain cloth.

New episodes of "Severance" stream Fridays on Apple TV+.

Read more

about "Severance"

Shares