Back in 2020, esteemed chef and James Beard-winning writer and cookbook author Alexander Smalls was deep in research about the foundations of African cooking and cuisine in preparation for an expo in Dubai.

He named the food hall Alkebulan, "which was the first written name of Africa," adding, "I was off and running. I created the whole concept, soups to nuts, every menu . . . you name it."

Then, though, Smalls noticed something was awry. "And then I had an ‘aha’ moment: How dare me, with great arrogance, tell Africans what African food is all about? And so I took the role of curator and I brought in African chefs," he said.

That realization led to his book “The Contemporary African Kitchen,” which bridges the gaps between Smalls' Gullah Geechee upbringing and the African culinary traditions that shaped his work. Smalls, who is gregarious and deeply knowledgeable about global foodways, approaches his craft with a reverence for both African and Gullah Geechee cuisine.

"The strength and power of the Gullah Geechee table"

Smalls drove home the idea that food is identity. "The extraordinary thing about the Gullah Geechee household is that that doesn't leave you. [My family] could have moved to Alaska. The concept of who we were was through the lens of our food, culture and heritage," he said.

Alexander Smalls (Photo by Rich Kissi)

Alexander Smalls (Photo by Rich Kissi)

His father's family was based in Spartanburg, South Carolina, at the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. But Smalls noted that his childhood meals were completely unlike those of his friends.

"So it was as if I lived in another world," he said. "And I say that simply to emphasize the strength and power of the Gullah Geechee table, which relates directly to the West African culinary expression."

We need your help to stay independent

For Smalls, food is a currency, a language, and a way for people of the African diaspora to connect with their heritage. "Nothing was clearer to me than when I first got on a plane and flew to West Africa and saw essentially a whole world of people who looked like my grandparents and talked like them."

From opera to the kitchen

Before Smalls was a chef, he was an opera singer. He grew up playing classical music and dreaming of a career onstage. "The world, to me, came alive through music," he said. "I knew I was an artist, but I also knew I was a culinary expressionist — a culinary artist — because my two languages as a child were food and music, and I was either doing one or the other."

The link between the two disciplines was clear to him. "First, it's all an art," he said. "And the lyricism of each of those disciplines — they intersect."

As a child in a "one-horse town in South Carolina," Smalls was drawn to Shakespeare and prose, spending time in his mother’s rose garden, despite the skepticism of those around him. "Everybody thought I had lost my mind," he said. But his parents never discouraged him.

"They were training me to be a doctor or lawyer, maybe the first Black president — not an entertainer. And opera? We didn't know anybody who did that," he said. "But they never said no. They supported all of it and hung in there with me."

Smalls said that foundation gave him the confidence to explore different forms of artistic expression. "That was the anchor that sort of pushed me into the arena of what I do. When I hit the glass ceiling so many times in opera — it was just not a welcoming place for Black men — it became clear that my career was going nowhere. And my second love was calling me, which was food."

Want more great food writing and recipes? Subscribe to Salon Food's newsletter, The Bite.

Building a culinary legacy

Smalls’ family was deeply rooted in the culinary world — many of his aunts and uncles worked in kitchens — so when he left music, he turned to food. But he noticed a glaring absence.

"There was no space, no place set at the table for African food and food of the African diaspora," he said. "So I decided when I left classical music, I was going to open the first fine-dining concept translating soul food, if you will, through the lens of fine dining and essentially create something that I had not seen."

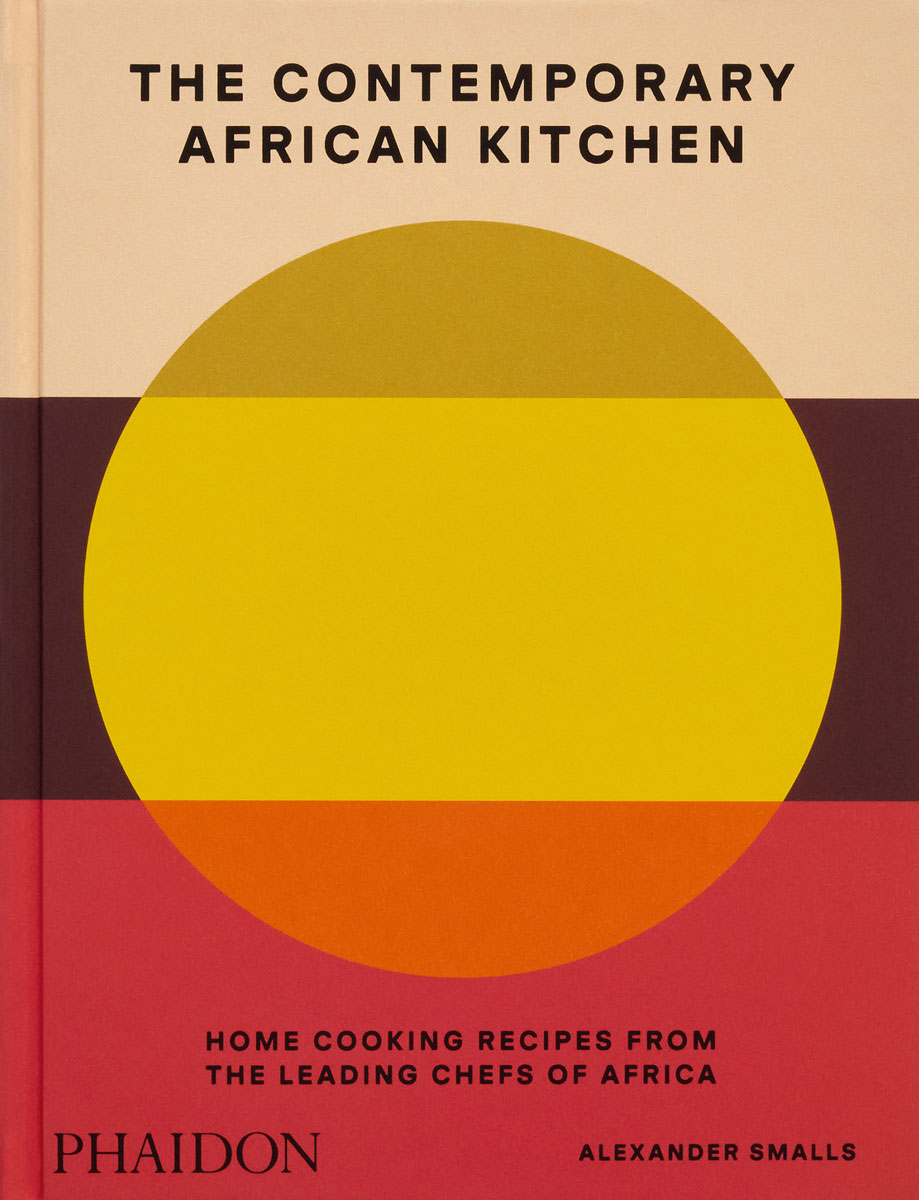

The Contemporary African Kitchen: Home Cooking Recipes from the Leading Chefs of Africa (Courtesy of Phaidon)

The Contemporary African Kitchen: Home Cooking Recipes from the Leading Chefs of Africa (Courtesy of Phaidon)

Thirty-five years ago, Smalls opened his first restaurant, Café Beulah, which set him on that path. His next three restaurants continued exploring Gullah Geechee low-country cooking, but after a decade in the industry, he took a hiatus to study the transatlantic slave trade and its impact on food culture. He traveled through South America, Brazil, and the Far East, tracing how African culinary traditions shaped global cuisine. That work culminated in his award-winning restaurant The Cecil.

COVID-19 shuttered his next project, the Harlem Food Hall, but then Smalls received an unexpected call from Her Excellency, the sheikh of Dubai’s daughter, which led to his work on Alkebulan.

Through it all, Smalls has remained committed to telling the story of African and diasporic cuisine. "I am a warrior for the food of the African diaspora," he said. His latest book, backed by Phaidon Press, is another step in that mission.

"They wrapped their arms around it, loved it, and gave me wings to fly."

Read more

about this topic