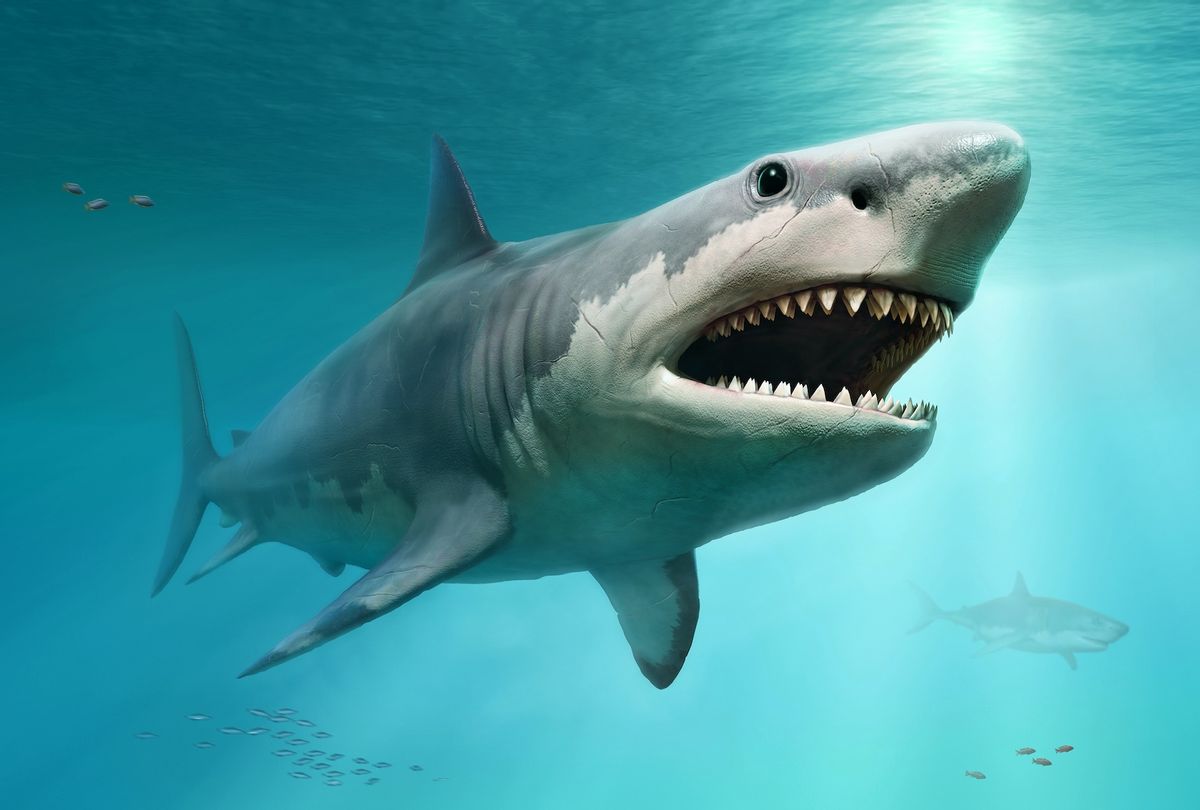

Fifteen million years ago, now-extinct species of dolphins, whales and large sea cows roamed the world’s oceans, topping the underwater food chain. Yet back then, any one of these creatures could become prey to the ocean's fiercest apex predator: the megalodon, a giant shark with massive teeth and a body the size of a whale.

In many ways, the so-called "monster shark" is regularly featured in TV marathons like "Shark Week" while spawning horror films like "The Meg." But the true size and shape of this extinct giant probably doesn't resemble the star of "Jaws."

Scientists have long debated the true size of the megalodon (Otodus megalodon), which went extinct about six million years ago. The debate remains unresolved in part due to sharks lacking bones and discovering cartilage skeletons is relatively rare. Still, several fossilized records of the megalodon have been discovered, and scientists have been able to piece together their best guess of what this massive shark probably looked like.

Based on one such spinal skeleton of the megalodon, a new study published in the journal Palaeontologia Electronica reports that the giant shark stretched 54 feet in length, or about the size of the cargo section of a semi-trailer truck. Because even larger megalodon vertebrae have been discovered elsewhere, the researchers also calculated that individuals of this extinct species could grow to be as large as 80 feet long, which is the average size of a blue whale and roughly equal to the height of the White House.

Finding out details about how this gigantic shark survived and eventually went extinct can help us better understand the potential consequences of other apex predators facing extinction today, researchers say.

“As one of the largest carnivores that ever existed, deciphering such growth parameters of megalodon is crucial to understand the role large carnivores play in the context of the evolution of marine ecosystems,” said study author Dr. Kenshu Shimada, who studies the evolution of marine ecosystems at DePaul University.

"It is more likely than not that megalodon must have had a much slenderer body than the modern great white shark."

With no living relatives alive today, megalodon sharks were unique in that they were endothermic (warm-blooded), similar to opah fish, great whites and certain species of sharks that are partially warm-blooded. This is thought to have been an advantage allowing these predators to regulate their body temperatures in cooler waters so that they can more efficiently hunt within their coastal habitats spanning across every continent except Antarctica.

On the other hand, being endothermic could have also contributed to megalodon's extinction, since constantly regulating body temperature like this would have expended more energy and thus required more food. The megalodon is thought to have gone extinct because a changing climate limited their food resources and great white sharks outpaced them evolutionarily as predators.

Because of the perceived similarities between the megalodon and the great white, with the two having similar teeth structures, prior research estimating the megalodon's size used the great white as a proxy. Jack Cooper, a paleobiologist at Swansea University, led a prior study using the great white and some of its relatives as a reference point to estimate the megalodon's size and found it would have measured about 49 feet in length. Prior estimates hypothesized that the giant shark could have stretched up to 65 feet.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

However, the current study did not use the great white as a proxy. Instead, the researchers compared the megalodon to more than 150 other species to estimate how big its head and tail were and then added those sums to the existing fossilized record of the trunk to get the full body length.

“Our research team found that the modern great white shark with a rather stout body hypothetically blown up to the size of megalodon would not allow it to be an efficient swimmer due to hydrodynamic constraints,” Shimada told Salon in an email. “For these reasons, our new study strongly suggests that it is more likely than not that megalodon must have had a much slenderer body than the modern great white shark, possibly as slender as the living lemon shark.”

Lemon Shark, Negaprion brevirostris, Bahamas, Grand Bahama Island, Atlantic Ocean (Photo by Reinhard Dirscherl/ullstein bild via Getty Images)

Lemon Shark, Negaprion brevirostris, Bahamas, Grand Bahama Island, Atlantic Ocean (Photo by Reinhard Dirscherl/ullstein bild via Getty Images)

While great whites are bulky, lemon sharks (Negaprion brevirostris) are more flat and elongated. The new study reports the megalodon to be slightly bigger than Cooper’s estimate. However, their analysis comparing various species to determine that the megalodon more closely resembled the lemon shark than the great white also includes whales, and it would have been helpful to see if this analysis held true with only shark comparators, Cooper said. For example, sharks move their tails horizontally and whales move them vertically to swim, which will have an impact on how their bodies move throughout the water, he explained.

“I get that approach because we are talking about a shark that is as big as a whale, basically,” Cooper told Salon in a video call. “But at the same time, whales and sharks swim in such different ways that it is naturally going to affect the hydrodynamics around them.”

We need your help to stay independent

Still, Shimada’s findings on how giant sea animals’ size affect their speed could help us better understand the evolution of large sea creatures today. Researchers in this study also revisited an analysis of fossilized placoid scales, or tiny tooth-like scales that cover sharks, from the megalodon. What they found was that these scales did not have ridges or keels typically found on fast-swimming sharks, and they estimated that the megalodon's cruising speed was between 1.3 and 2.2 miles per hour — about the same speed as the great white.

“Living gigantic sharks, such as the whale shark and basking shark, as well as many other gigantic aquatic vertebrates like whales have slender bodies because large stocky bodies are hydrodynamically inefficient for swimming,” Shimada said. “In contrast, the great white shark, with a stocky body that becomes even stockier as it grows, can be 'large' but cannot pass 23 feet to be 'gigantic' because of hydrodynamic constraints.”

The true size of the megalodon will remain open for debate unless a complete fossilized skeleton is discovered, Cooper said. With the chances of that being slim, studies like this can help piece together hypotheses on how this giant creature once carried itself throughout our ancient oceans.

“We’re still going to see this as a gigantic shark that was eating whales, partially warm-blooded, and able to migrate,” Cooper said. “What we’re going to take away from this study is that we get a new hypothesis as to what the shark looks like and that its body mass was probably not quite as chunky as we thought it was.”

Shares