For much of our history Americans have been enchanted by a fable of their own invention: that we are one people, that “America” means more or less the same thing to us all. If it has done nothing else, the political turmoil of the past decade has revealed the hollowness of that notion. In fact, polarization is fused into the very foundation of the American project.

In the late summer of 1664, an English military officer named Richard Nicolls led a flotilla of four warships across the Atlantic with the intention of transforming the nascent American colonies. After a long and bloody civil war that had pitted the religious militants known as the Puritans against the Stuart monarchy, the royals were once again in power in England, and Charles II and his brother James, the Duke of York, were eager to begin building an empire.

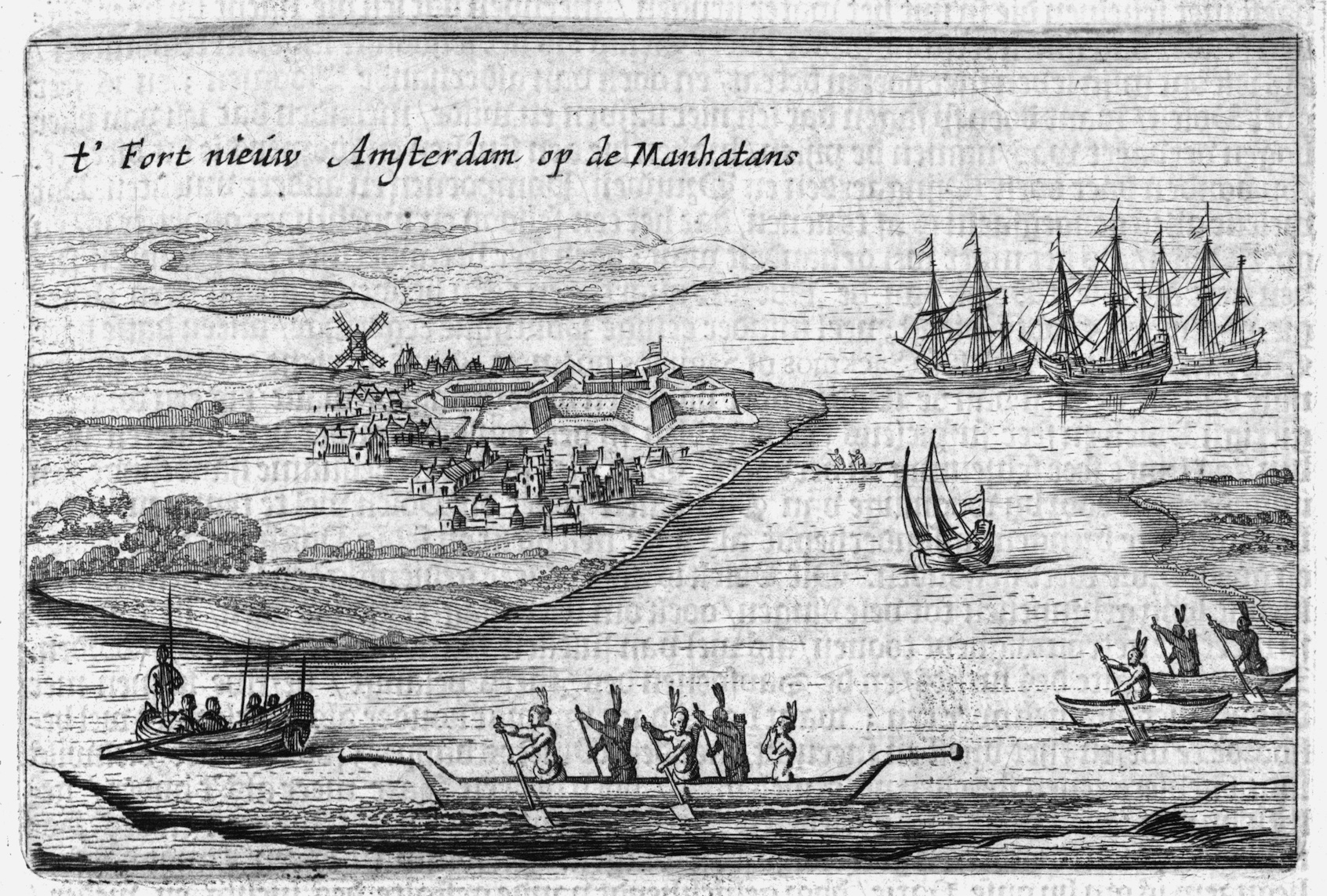

Nicolls, their dutiful operative, had two missions. The first was to wrest Manhattan Island from the control of the Dutch, whose colony of New Netherland had existed for 40 years. Nicolls was armed and ready for battle — the two nations were bitter rivals. Surprisingly, however, he engaged Peter Stuyvesant, the Dutch leader, in negotiation. They discovered they had much in common. The royalist faction in England were essentially moderates, who believed in religious liberty, wanted global trade and founded the Royal Society to advance science. The Dutch were all about those same things. Rather than fight, Nicolls and Stuyvesant effected a merger. Under their agreement, the city of New Amsterdam would keep its mixed population and the Dutch features of capitalism and relative tolerance, but the settlement and its inhabitants would transfer to English rule. Nicolls proudly wrote James that he had renamed the city with one of his titles: “I gave to this place, the name of N. Yorke.”

Then Nicolls turned to his other mission. Decades earlier, the Puritans had planted colonies in New England, with Boston as their base. Nicolls and his emissaries were to bring the Puritans there to heel, to compel them to put aside recent differences and respect the king and his government. But the Puritans had established a powerful theocratic rule, crushing political opposition and religious diversity with violence. They considered the Stuarts and their followers to be godless and corrupt, while they saw themselves as the chosen people. Nicolls got nowhere with them.

For the Puritans' descendants, the American system of government that was forged in the 18th century was only ever a vehicle to get to the promised land.

Few Americans have heard of Richard Nicolls, but today we are living with the fallout from his two missions. New York and New England went on to become competing centers of power and ideology: one pluralistic and globally-minded; the other moralistic, monocultural and, well, puritanical. The geography shifted over the centuries, but these ideologies each grew along with the nation. Indeed, you can read American history — from the Civil War to Reconstruction to the civil rights movement to the age of Trump — as a long, Manichaean struggle between two opposing belief systems.

The creation of the American republic was a valiant attempt at uniting the two sides, but the founders themselves were well aware of the gulf, and of how differently each saw the new nation. The philosophical descendants of the Puritans believed the call to freedom that was embedded in the founding was meant for white Christians. As it evolved in the 19th century, this ideology held that the country was a promised land, the “city upon a hill” that Puritan leader John Winthrop of Massachusetts spoke of. This America had a theological destiny – a manifest destiny, as it was termed in the 19th century by a pro-expansion, pro-slavery champion – “to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.”

We need your help to stay independent

The rival ideology, meanwhile, viewed the cry for freedom in the Declaration of Independence as only a first step. Over time, its adherents pushed for the abolition of slavery, for women’s suffrage, for civil rights for all, for same-sex marriage. As the left has ventured into new territory — trans rights, Black Lives Matter, land acknowledgments — the right has shifted in the other direction, embracing racist and “tradwife” tropes that no politician would have dreamed of employing a decade ago. Then, finally, a dam burst and, in the eyes of millions of latter-day Puritans, one man stepped forward who was brave enough to speak the truth.

Republicans were the first to realize the hollowness of the myth of one America, and to act. Wokeness woke them, led them to see the other side as beyond their moral boundaries. Some on the right were goaded by media outlets that used wild exaggerations and downright lies to portray people on the left as cartoon effigies of evil secular impulses, but setting aside the lies and distortions, a great many people felt a genuine abhorrence for pluralistic, secular society and a government that based policy on cold scientific studies and New Agey concepts of radical equality rather than on biblical or other traditional precepts.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Some on the left are shocked by the willingness of Republicans to follow President Trump into anti-constitutional territory, but for the Puritans’ descendants the system of government that was forged in the 18th century was only ever a vehicle to get to the promised land. America as a joint project was useful while the myth held. Today’s Puritans have shown in innumerable ways that they have seen through the myth and have moved on: from refusing to consider Barack Obama’s Supreme Court nominees to rejecting the results of the 2020 election to redefining the Jan. 6 insurrection as an act of patriotism to Vice President JD Vance’s recent reprise of Trump’s “enemy within” trope to the moves the Trump administration is now taking toward autocracy.

Democrats still haven’t fully awakened from the dream of America as a joint project – think of Joe Biden’s quaint-sounding use of the phrase “my Republican friends” – though they are now tossing and turning in their sleep. What you might call an inherited trauma has defined us from the start. Unless Republicans have a radical change of heart and find that they would rather work alongside their ideological adversaries for the good of both than follow their president into a strange future of chaos and despotism, the non-Puritans among us need to accept that an accidental experiment, which began nearly four centuries ago with Richard Nicolls’ twin missions and which was rooted in the European struggle between faith and reason, is at an end.

Like an otherwise sturdy building with a flawed foundation, the myth of one country held for a good long time then collapsed in a rush. We don’t know what the new structure will look like yet or who will build it, but one side already has its blueprints and has started hammering.

Read more

about America's history wars