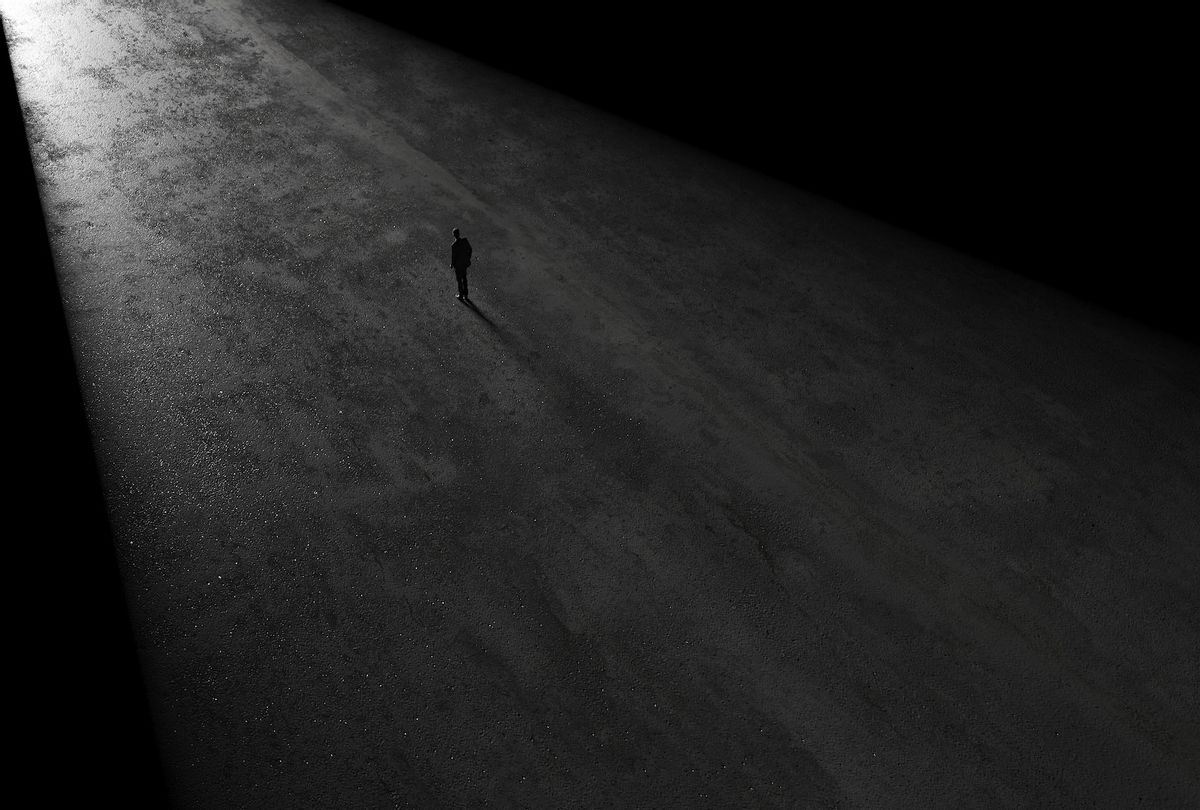

In the modern world, we can become overwhelmed with news of the collapse of our ecosystem, the chances of another pandemic, and global warfare, plus the latest political crisis — all within 15 minutes scrolling on our phones. As our brains struggle to process information related to major threats, it's natural to feel completely drowned in anxiety, frozen and unable to do anything except keep doomscrolling. Psychology can help us understand why our reaction to a stressful world isn't always fight or flight but paralysis — and it can help with breaking free from that feeling of helplessness.

In the 1960s, neuroscientists studying how animals reacted to stressors came across a surprising finding. Animals were put into an environment that delivered electric shocks no matter what the animal did to try and avoid them. Afterward, the animals were placed in a new setting where they could escape the stimuli. But, sadly, they stopped trying to escape — as if they had given up.

The authors concluded that the animals had learned they had no control over the situation and named the phenomenon “learned helplessness.”

While this science helped researchers better understand depression because it shares some similar characteristics, it has also helped them better understand how we can build resiliency in the face of stressors. And it turns out that a lot of what they learned has to do with exerting control over the situation — or, in other words, empowering ourselves.

“If you take two animals and give them the exact same stressors but make one animal feel like they can control the stressor, the animals who have the sense of control have better outcomes than the animals who don’t have the ability to control the stressors,” said Dr. Mazen Kheirbek, a neuroscientist at the University of California San Francisco. “It’s almost like the ‘learned’ part of learned helplessness is learning that you lack control.”

During an election cycle, news outlets like to report that the American public is living in a state of learned helplessness, which anyone who feels like they are being barraged with a flood of unpredictable stressors can certainly relate to. In fact, more and more people are tuning out the news completely to avoid feeling lousy from the chaotic directives from the Oval Office and multitudes of global crises.

"It’s almost like the ‘learned’ part of learned helplessness is learning that you lack control."

“Think about what’s happening right now in the entire country: Some people more than others are experiencing a sense of learned helplessness,” said Dr. Helen Mayberg, a neuroscientist at Mount Sinai who studies deep brain stimulation for depression, describing a sense of "‘no matter what I do, there is not an escape route.’”

While the two are not mutually exclusive, learned helplessness is also thought to play a role in depression. In experiments that put animals into a state of learned helplessness, those animals also tend to eat less and show a general lack of motivation and pleasure.

“We have a system in our brain that is designed to move away from stress,” Mayberg told Salon in a phone interview. “What happens in depressed people is, you end up having a sensation of anhedonia, where it’s not worth it to move towards the reward, or you develop learned helplessness, where you need to move but you cannot.”

Many antidepressants, along with deep-brain stimulation and ketamine, work by activating the same pathways in the brain involved with learned helplessness, Mayberg said.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

“When we put in a brain implant in this area … the first sensation patients have is that the negative seems to get lighter and they have the sensation that they can now move when before they couldn’t,” Mayberg said. “I have learned over time that the mental pain is related to the inability to move.”

On the nonpharmacological side, other forms of treatments work with this system in the brain, too. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy is based on empowering people to change unhelpful thoughts and behaviors to improve their mood. Meditation and mindfulness can help people change how they respond to stressors — so that even when external circumstances are in fact out of their control, at least they can develop the tools to control their reaction to them.

"Why do people learn to be mindfully meditative?" Mayberg said. "It's not because it's totally protective, but it gives you a strategy to not let these incoming things kind of take over."

Over the last several decades, neuroscientists in the field have begun to better understand how the concept of learned helplessness relates to resiliency. Studies in humans suggested that having control activates the prefrontal cortex — one of the most recent parts of the human brain to evolve that is associated with cognition, decision-making and motivation.

And this activation in the prefrontal cortex can effectively block the stress response triggered in other parts of the brain, said Dr. Michael Baratta, a neuroscientist at the University of Colorado Boulder. One 1998 study, for example, found that people who had perceived control over a painful experience reported feeling less pain.

This defense mechanism in the brain makes evolutionary sense because early organisms had limited ways to respond to threats, relying mostly on physiological reactions like altering their immune response, changing their pH, inducing camouflage, or hiding, Baratta said.

“But because they can’t really exert control over their environment, their brains aren’t designed to be sensitive to control,” Baratta said. “So my take is that as species evolve to have more complex behaviors, they can actively manage threats once that becomes possible.”

It’s important to note that a host of individual factors influence whether someone becomes depressed and that mental illness like depression shouldn’t be written off as the result of someone not taking control over their situation.

“It doesn’t mean that a vulnerable person can’t get depressed, and it also doesn’t mean that a person who is naturally resilient can’t be faced with enough stressors that they get sick,” Mayberg said. “You can do all the right things to mitigate risk, but you still have unknown triggers that may supersede your control over the risk.”

We need your help to stay independent

Still, in studies, this protective effect that a sense of control produced held strong even when that control was in relation to something besides the acute threat. This indicates that it can help mitigate the negative effects of facing a threat we face if we empower ourselves in other aspects of our lives that are unrelated to the threat. For example, remaining active and building relationships with friends, family and local communities. The small decisions we make in our day-to-day lives can have an impact on unrelated stressful situations that feel out of our hands.

“You focus on the things that you have control over: I can exercise. I can make sure I don’t use this as a reason to eat bad things,” Mayberg said. “I can focus my attention on something that I do have control over, small or big.”

Today, researchers understand that animals, including humans, don’t “learn” to be helpless. Our default response is to freeze and avoid a threatening situation. But we can learn to overcome the threat and escape.

“What has turned out to be critical from years and years of research is peoples’ self-perceived ability to cope with the event in question,” said Dr. Steven Maier, one of the co-authors on the original paper pioneering this research, at a talk in 2015. “At the heart of coping is the person’s perception to the degree to which they have behavioral control over the circumstance that has occurred, the degree to which they believe their own personal actions can influence the outcome.”

Shares