On the night of August 16th 2017, three police officers dragged 17-year-old schoolboy Kian delos Santos through a filthy alleyway in the sprawling Philippine capital of Manila and shot him three times in the head. Witnesses heard Kian pleading with the officers before he was executed, telling them he had exams the next day. The cops then left his body slumped next to a pigsty as they claimed he pulled out a gun and started blazing.

Kian’s murder sparked unprecedented outrage. 5,000 mourners showed up for his funeral which turned into a protest march with signs reading “Stop the Killings” and "Run, Kian, Run."

Among those at the procession was Catholic priest Father Flavie Villanueva.

“Whenever I join a funeral march, I would always find myself walking beside the hearse and people have asked me, why do I do this?” he told Salon. “My immediate response was, 'I know how it is to be left out, to be singled out and to walk alone.' And this is what precisely this person felt. He was abducted alone. He was gunned down alone. And he suffered and died alone. I wouldn't want to do that to them now, even if it's kilometers and kilometers of walking.”

Kian’s death was not an isolated instance of police brutality. It was part of a systematic massacre of so-called “drug addicts” and “pushers” orchestrated by then-president, Rodrigo Duterte.

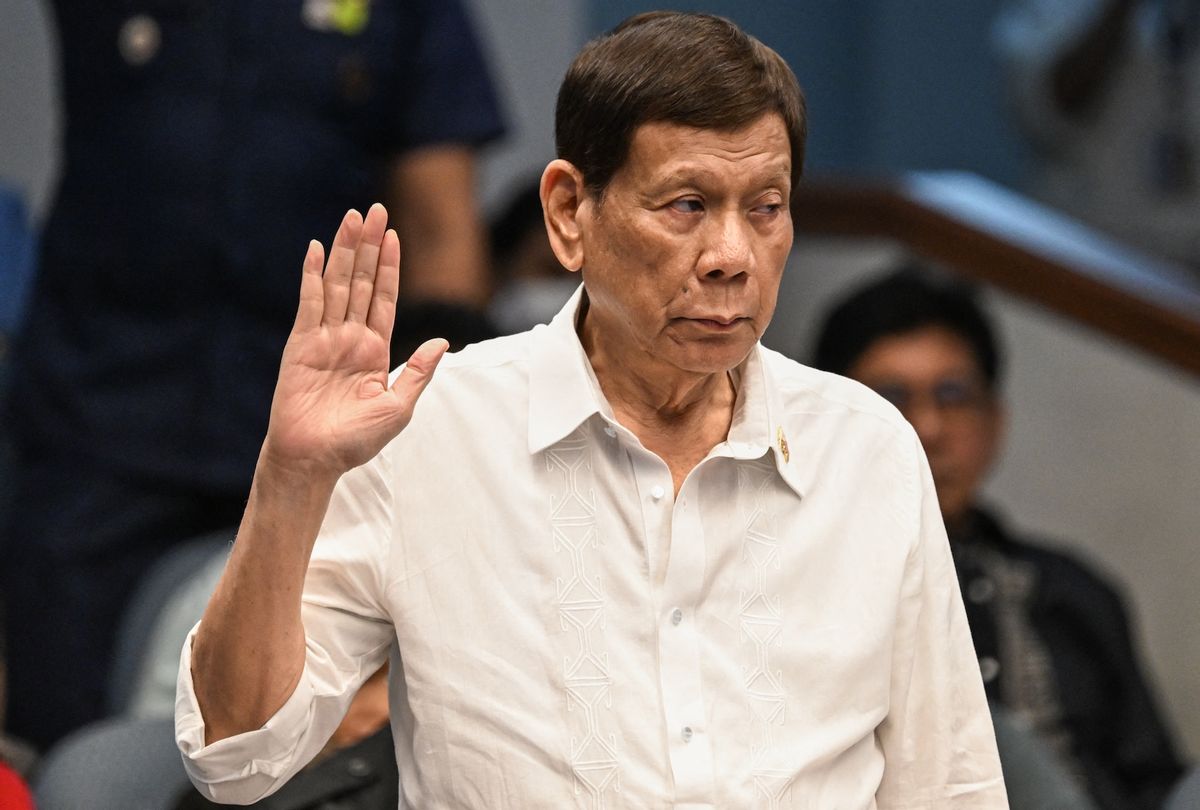

“I have to slaughter these idiots for destroying my country,” Duterte declared in his inaugural State of the Nation Address. As many as 30,000 Filipinos may have been slaughtered over the course of Duterte’s six year reign, from 2016 to 2022. Since no due process was afforded to them, it’s likely many, like Kian, were entirely innocent. The International Criminal Court brought charges of crimes against humanity — normally filed against genocidal dictators — and on March 11, Duterte was arrested in Manila upon his return from Hong Kong and placed on a plane to The Hague.

For a while, it seemed like he’d get away with it. Under his tenure the Philippines had withdrawn from the ICC, while his daughter Sara had been elected vice president. But tensions between the Dutertes and current president Ferdinand Marcos Jr., son of kleptocratic despot Ferdinand Marcos, left him vulnerable.

"That’s beautiful," Duterte remarked on hearing 32 people had been killed in one night.

“There was suspense when he was returning from Hong Kong, because I know he was trying to bargain an asylum,” Villanueva recalled. “From the fact he returned, we can conclude China denied his request. And when it came, when the warrant was finally served, the question was ‘Will they be able to bring him out of the country?’ When the jet took off, that was the only time we opened the champagne. The feeling, in a word, is jubilant. It allowed me to sing hallelujah in the Lenten season,” referring to the run-up to Easter.

The Philippines, an archipelago of more than 7,000 islands in Southeast Asia, had long been ruled by a succession of dynasties, out-of-touch with ordinary Filipinos, and their cronies while wealth inequality deepened. Along came Rodrigo Duterte, a swaggering ruffian from the southern island of Mindanao, whose 1998 psychological assessment concluded he had a “pervasive tendency to demean, humiliate others and violate their rights.”

Former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and former Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea were on board the jet to The Hague on March 11, 2025, for Duterte's trial at the International Criminal Court on 11 March 2025. (Senator Bong Go / Wikimedia Commons)

Former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and former Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea were on board the jet to The Hague on March 11, 2025, for Duterte's trial at the International Criminal Court on 11 March 2025. (Senator Bong Go / Wikimedia Commons)

The Philippines has a long history of death squads. During the 1980s, right-wing vigilantes known as Alsa Masa (“Masses Arise”) carried out murders and abductions of real and suspected communists amid an insurgency by the New People’s Army (NPA), which deployed its own hit squads called the “sparrows.” In rural provinces, strongmen wielded their own militias: in 2009, 58 were slain in a massacre ordered by a powerful clan seeking to prevent another clan challenging them in local elections.

As mayor of the crime-ridden Davao City, Duterte admitted to leading the Davao Death Squad composed of ex-cops and NPA defectors who executed hundreds of small-time drug users, peddlers, thieves and street kids, plus the occasional unlucky witness. The youngest was reportedly 12-years old. From 1998 until 2015, they’d racked up a body count of 1,424. The hitmen were paid monthly salaries plus bonuses for each job, and victims were often executed in a quarry — the women sometimes raped. Ex-killers turned whistleblowers claim Duterte got his hands dirty too, emptying two full Uzi clips into an investigator.

In 2016, embracing the popular rage against the elites and bolstered by an army of Facebook trolls, Duterte won the presidency. Fascist demagogues always need to rally against an opponent, and Duterte found his in drugs, which he claimed were drowning the country. He pledged to expand the Davao Death Squad model nationwide.

“These human rights [advocates] did not count those who were killed before I became President. The children who were raped and mutilated [by drug users],” he told a crowd.

“I’d like to be frank with you,” asked the president. “Are they humans? What is your definition of a human being?”

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

The scourge of society was seen as shabu, or crystal methamphetamine. There was a criminal element, of course, but it was mostly blue-collar workers and street vendors who took it to endure tiring shifts, using the euphemism pampagilas or “performance-enhancer.”.

The killings began as soon as Duterte stepped into office. Extrajudicial killings typically came in two varieties: a drug suspect gunned down by police while supposedly resisting arrest, or a purported pusher dispatched by unknown hitmen.

The first type typically went as follows: dealers under surveillance were approached by an informer or undercover, made a sale, then opened fire on the cops when they closed in. “Nanlaban sila,” the officers replied when asked what happened, meaning “They fought back.”

“That’s beautiful,” Duterte remarked on hearing 32 people had been killed in one night. “If we can kill another thirty-two every day, then maybe we can reduce what ails the country.”

It’s remarkable how the cops achieved a near-total kill rate (few suspects were merely left wounded) while rarely suffering casualties themselves. The death rate perpetuated stereotypes about drug dealers willing to shoot it out to the bitter end, risking the lives of their loved ones nearby and despite knowing the cops don’t miss. Weapons and sachets of meth were invariably found next to their corpses — sometimes handguns with the same serial numbers would appear at different crime scenes.

The death squads were on the payroll of the police, if not actually being the police themselves.

The local Commission on Human Rights said nearly all cases it investigated uncovered mischief on the part of the police: covering up evidence, signs of torture. And yet, as of last year there have only been four convictions of police officers for unjust killings, including the trio who murdered Kian delos Santos. Perhaps this might change with Duterte in the dock.

In congressional hearings last year, Duterte himself admitted encouraging officers to provoke suspects, and the hearings also revealed cops received bonuses for each target eliminated — incentivizing murder. The police drew up their kill lists based on names volunteered by the community; in other words, if you’ve got beef with your neighbors, just claim they’ve been dealing meth.

Other times victims were found with their hands bound in duct tape, wrapped in plastic sheets, next to a sign reading “drug pusher huwag tularan” or, “I am a drug pusher, don’t imitate (me).” Officially warring gangsters or private citizen vigilantes were blamed, but in reality the death squads were on the payroll of the police, if not actually being the police themselves.

Duterte’s anti-drug campaign attracted attention overseas as suspicious accounts of police shoot-outs were reported in Bangladesh, while the president of Indonesia ordered his officers to deploy deadly force.

“I just wanted to congratulate you because I am hearing of the unbelievable job on the drug problem,” Donald Trump, then on his first term as commander-in-chief, told Duterte in a phone call. “Many countries have the problem, we have a problem, but what a great job you are doing and I just wanted to call and tell you that.”

But according to the Filipino police’s own data, in the first three years of the campaign they’d managed to interdict only an estimated 1% of the nationwide shabu supply and cash earned from its sales.

Meanwhile, only a tiny fraction of victims were powerful movers and shakers in the narco-economy: an estimated 2% were officials or politicians, and 1% were kingpins. The rest were largely working-class, in low-wage jobs or unemployed. In some instances, the families couldn’t even afford to bury their dead, only rent space in tightly-packed urban cemeteries.

Father Villanueva, a priest, gestures during the funeral march for 17-year-old student Kian Delos Santos, who was killed allegedly by police officers during an anti-drug raid, in Manila on August 26, 2017. (NOEL CELIS/AFP via Getty Images)

Father Villanueva, a priest, gestures during the funeral march for 17-year-old student Kian Delos Santos, who was killed allegedly by police officers during an anti-drug raid, in Manila on August 26, 2017. (NOEL CELIS/AFP via Getty Images)

“When Duterte came into power, I felt compelled to help rebuild and empower the lives of the widows,” Villanueva said. “There was a great need to rebuild their lives that were shattered and traumatized, to empower them so that they would feel taking responsibility for what they need to do to be the breadwinners and to become agents of social transformation of the country.”

Villanueva manages Program Paghilom, which provides food, counseling and legal assistance to grieving families, as well as paying for orphans’ schooling and exhuming, cremating and blessing the victim’s remains when their lease expires in the cemetery. They’ve also built the first memorial for drug war victims.

“It was perhaps my penance for having voted for the devil,” he added, shyly admitting to having voted for Duterte.

Villanueva became publicly outspoken about the drug war, earning him the ire of Duterte supporters. At one point, Villanueva and Jesuit priest Albert Alejo were charged with sedition for allegedly making videos implicating the Duterte family in drug trafficking themselves (Duterte’s close associate and onetime economic advisor Michael Yang has been accused of being a major meth baron in Mindanao). They were later acquitted, but the pressure is still on Villanueva.

“I've had four surveillance security issues since January — visits from unknown people, tailing on motorcycles,” he said. “A motorcycle stopped in front of me to ask how am I doing, mentioning my name, and after a snappy conversation, he left with a smile saying, ‘take care, Father Flavie.’ [And] a visit from people in another house where I celebrate mass who insisted that they see me, but I don't live there and the sisters who received the visitor were helplessly pointing to where I live. And I was telling them, ‘you know, sisters, you really are very generous. You give things that are not supposed to be given away!’”

Victims’ friends and relatives, too, are often harassed and intimidated by police, and threatened if they speak out.

We need your help to stay independent

“Even to this date, the stigma that they are victims of the war on drugs is still very much alive,” said Villanueva. “During the pandemic, they were singled out as either the last or zero recipients of aid from whatever agencies would offer the communities. They've been labelled, bullied, both in the communities and social media.”

And yet, despite all the terror and bloodshed, Duterte left office with an 81% approval rating — one of the most popular rulers of the Philippines. After his arrest, supporters held both protests and celebratory rallies in both Manila and The Hague.

So does a guy riding up and blasting you with a Glock because you took a hit from a meth pipe at least constitute an effective drug policy? According to the Dangerous Drugs Board, after three years of the drug war, the number of regular drug consumers fell by only 4.5%. By 2023, the total reduction from pre-Duterte levels was estimated at 17% — not unsubstantial, but it’s worth considering that drug deaths in America plunged by a similar level in just one year, from 2023 to 24, without any masked assassins in balaclavas dispensing state-sponsored street justice.

It’s also worth remembering that in Western countries, we too are waging a drug war against our poor and underprivileged. Duterte’s rage is simply the logical end point of our own lack of sympathy and understanding towards consumers of illicit substances, and demonization of those who sell them. Even if we don’t put a bullet in their dome directly, we make their lives hell with arrests and prison spells, let them die entirely preventable deaths through a toxic drug supply, and maintain the business model of brutish gangsters and thugs.

“I pray that this arrest would also address the ignorance of Filipinos thinking that evil will succeed,” Villanueva smiled. “Yesterday was a very stark statement that evil may linger, but there will always be a day of reckoning where good will triumph over evil.”

Shares