In 1807, President Thomas Jefferson founded the nation’s first scientific agency. It was tasked with surveying the coasts of the United States. Roughly 60 years later, a national weather bureau was created, and a fish and fisheries commission soon followed. The focus of these three agencies was eventually brought together in 1970 as part of the new National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA. Today, agency staff study the ocean and atmosphere, share knowledge, and conserve coastal and marine ecosystems. Under the new administration of Donald Trump, this agency with 218-year-old roots is undergoing another significant change — one that experts fear could significantly hamper NOAA’s work.

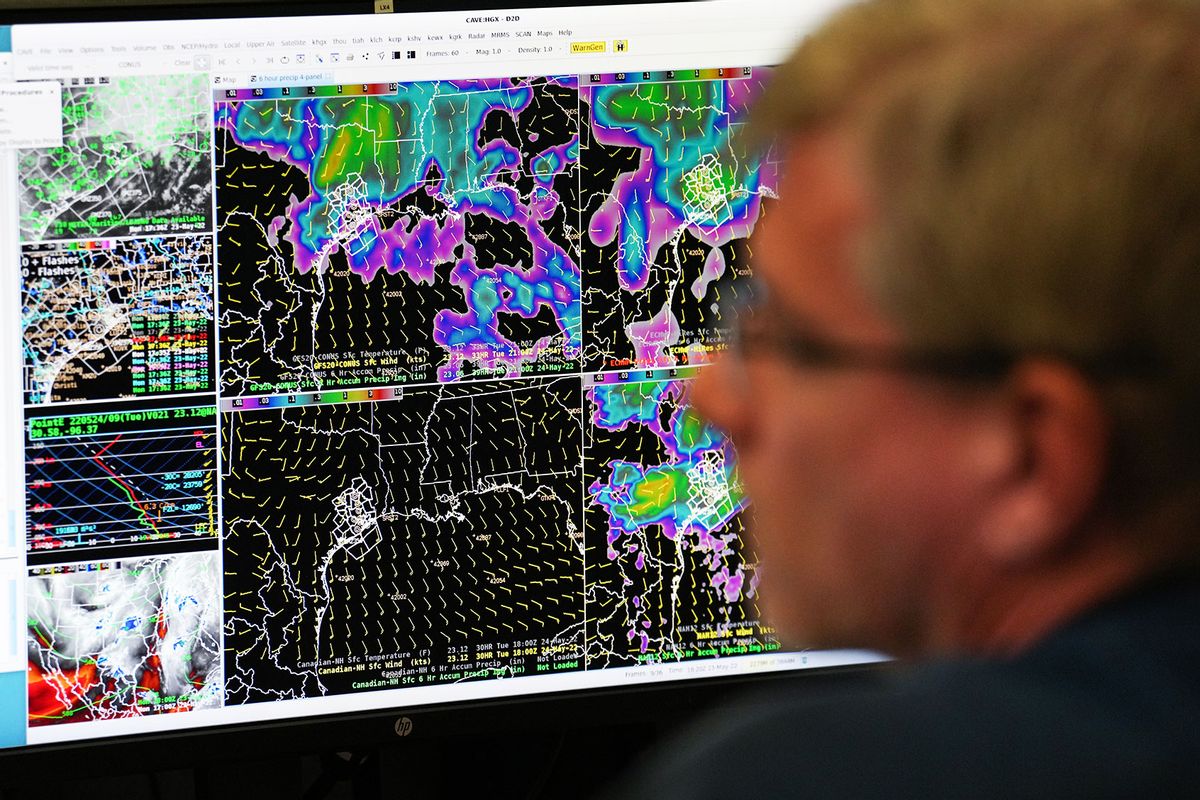

In fiscal year 2024, NOAA accounted for more than half of the Department of Commerce’s budget and, as of recently, it had about 12,000 employees worldwide. The agency has a broad portfolio of activities, including gathering data and monitoring oceans, the atmosphere, fisheries, and marine life. The National Weather Service, a NOAA sub-agency, provides weather forecasts that include watches and warnings used to protect people and their property. To carry out its work, NOAA has at its disposal an array of tools, including satellites, airplanes, weather balloons, maritime buoys, and radar systems.

Under the direction of the Department of Government Efficiency, the administration’s cost-cutting effort, CBS reported that 880 NOAA employees were let go in late February. In March, a U.S. district judge ordered thousands of fired federal workers to be temporarily reinstated, but many have been put on administrative leave. The administration has also discussed possibly terminating leases for properties housing NOAA operations. Moreover, all federal agencies are currently subject to a purge of certain words and phrases. The New York Times has found that “climate science” is among them.

“One could make a strong case that NOAA was under-resourced and under-staffed before these cuts, so this is simply making the situation worse,” wrote Keith Seitter, former executive director of the American Meteorological Society, in an email to Undark. This could lead to dangerous delays in forecasting extreme weather events like tornadoes and hurricanes, in addition to hampering climate research. Private entities aren’t likely to be able to fill the void, Seitter noted.

“There seems little question that these cuts are going to severely impair NOAA's ability to carry out its mission,” he wrote.

Trump and hissupporters have long criticized NOAA's climate research efforts as being politically motivated. Project 2025, a sprawling document created by the conservative Heritage Foundation, describes NOAA as a main driver of the “climate change alarm industry," and suggests the climate research of one of its divisions ought to be "disbanded." The document further states that some of NOAA's other functions could be carried out in the private sector “at lower cost and higher quality.” The National Weather Service, for example, could be commercialized, according to Project 2025.

Massachusetts-based meteorologist Brian Gonsalves wrote in an email to Undark: “We are already seeing immediate impacts from these cuts, which will only worsen if further cuts are made.” The reduced staffing could make it more difficult to gather and process the data coming in from across the country — on temperature, wind speed, and dew points, among other things. The end result may be a decline in the agency’s ability to produce accurate weather forecasts, he said.

This may ultimately put people’s safety at risk. Seitter, currently a visiting professor of environmental studies and geosciences at the College of the Holy Cross, pointed to the arrival of spring’s severe weather season. “It would not be a surprise to see insufficient staffing available to do some of the really important planning and preparation with state and local emergency managers,” he said. This could compromise forecasts of and preparations for tornadoes, for example, that have ripped through parts of the country in March with more likely throughout spring. Hurricane season, which extends from June to November, could be an issue, too.

Privatizing the National Weather Service would have additional implications, not only for ordinary people wanting to check the weather, but also for private entities that rely on data generated by the federal government. For instance, companies like AccuWeather depend on data collected by NOAA, among other sources.

On X, Tony Pann, a Maryland-based meteorologist, posted: “The information on your phone app comes from data provided by NOAA for free. NOAA gathers weather data (daily balloon launches) and feeds it into the modeling so your phone can tell you it’s going to rain tomorrow. Saying we don’t need NOAA or the NWS because I can see the weather on my phone, is like saying we don’t need farmers because I can just go to the grocery store.”

Project 2025, a sprawling document created by the conservative Heritage Foundation, describes NOAA as a main driver of the “climate change alarm industry."

It would be extraordinarily difficult for private companies like AccuWeather to do its work in the absence of NOAA-provided data, according to the meteorologists who communicated with Undark. Gonsalves, for example, said “it's impossible to adequately fill the void from a forecasting standpoint, as well as data collection for climate study.”

Seitter echoed this opinion, noting that the business models of private companies “are built on the foundation of a strong NOAA providing data from which they can create specialized products and services.”

Yet more cuts could be on the way. During the presidential campaign, Trump pledged to rescind unspent funds earmarked for climate mitigation in the Inflation Reduction Act, which was signed into law by President Joe Biden in 2022. Through the IRA, Congress allocated billions of dollars in resources to counter or prevent the effects of climate change, particularly in areas most likely to be affected, such as coastal cities. The IRA also funded efforts to improve NOAA weather forecasting capabilities.

All of this could lead to a worsening of climate change by reversing progress made in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The U.S. might well relinquish its role as a global leader in climate research and forecasting. And with NOAA’s monthly climate change briefings indefinitely suspended in April owing to personnel reductions, staff may become less aware of what, precisely, is happening to the climate.

And as CBS News reported in February, a former top NOAA scientist in the first Trump administration, Craig McLean, is worried about the politicization of science could undermine objectivity going forward.

“We are already seeing immediate impacts from these cuts, which will only worsen if further cuts are made.”

McLean gave as an example so-called Sharpie-gate, which occurred in 2019, when President Trump claimed that Hurricane Dorian would hit Alabama and displayed an altered graphic in front of news cameras to show the direction the storm would take. After an X account for the National Weather Service office in Birmingham, Alabama posted on social media that the hurricane would not impact Alabama, Trump’s staff apparently pressured Neil Jacobs — Trump’s current pick to run the agency — to say the forecasters had been wrong.

Trump has denied human-caused climate change, calling it “one of the great scams of all time.” And now the president oversees agencies such as NOAA and the Environmental Protection Agency, which traditionally have conducted climate research work predicated on the long-standing scientific consensus that emissions of greenhouse gases caused by human activity are primary drivers of global warming. Lee Zeldin, the EPA administrator, went so far as to call climate change a “religion” at a briefing in March, outlining steps his agency would undertake to deregulate. Jacobs could very well follow suit.

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.

Shares