Leslie spent her time in jail on a mattress on the floor in the day room because there were no cells available. Four months pregnant, she spent one agonizing day there withdrawing from opioids before she had a seizure and had to be rushed to the emergency room.

“They knew I was pregnant when I was being arrested because the officer threatened to throw me on the ground, and I told him, ‘Please, I’m 16 weeks pregnant — don’t,’” Leslie, who is using her first name only for privacy reasons, told Salon in a phone interview. “I told the officers … that I would be going through withdrawals, and I was already going through withdrawals when I was arrested.”

Withdrawing “cold turkey” from opioids while pregnant increases the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and stillbirth. Opioid withdrawal causes severe pain, nausea, vomiting and in rare cases, seizures. Withdrawing from some substances, including alcohol, can be fatal.

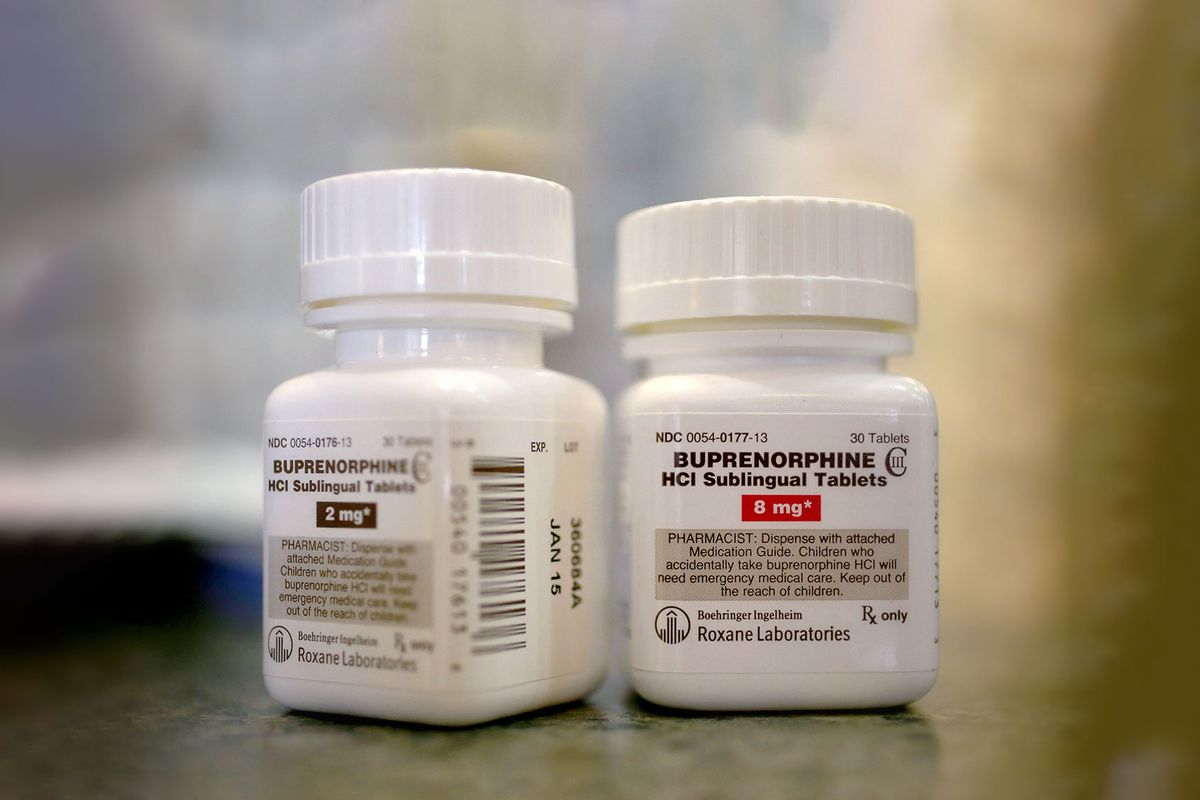

Medication-assisted treatment with medicines like methadone or buprenorphine is the standard of care for pregnant people with substance use disorders who are withdrawing because it can drastically reduce these health risks. Yet medicines like buprenorphine and methadone are not always available to pregnant people who are incarcerated.

Shanya, also in North Carolina, withdrew from opioids while pregnant in jail without access to medication-assisted treatment as well.

“It was not a good living situation,” Shanya, who is also using her first name only for privacy reasons, told Salon in a phone interview. “It was dirty. And I had a shower that never cut off, so the floor would be drowning and there was mold all in there.”

Anecdotes from pregnant people paint a grim picture of the state of maternal health care in the carceral system. Women have been reported living in degrading conditions and giving birth shackled to their bedposts. In 2023, a woman in Tennessee gave birth by herself on the jail floor. Dr. Hendrée E. Jones, director of the Horizons Program for pregnant women with substance use at the University of North Carolina, said she had one patient who had a miscarriage by herself on a jail floor.

“Jail is not the place that creates a context for healthy pregnancies,” Jones told Salon in a phone interview.

"Jail is not the place that creates a context for healthy pregnancies."

Still, there is not a clear picture of what maternal health care looks like in this system because there is no national database tracking the health of pregnant people who are incarcerated, said Dr. Carolyn Sufrin, an associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine who started a research center dedicated to studying reproductive wellness and incarceration to better understand how pregnant women in prisons and jails are being treated. Sufrin estimates that roughly 8,000 pregnant people with substance use disorders are admitted to prisons and jails each year based on data collected through this project.

Her research has demonstrated how variable the experience of a pregnant person with substance use while incarcerated can be. Some jails might not have a doctor or nurse on staff that can provide prescriptions, having to transport people with medical needs to a local hospital for care. Others may have them on staff, but with limited hours. And some have managed to find a way to administer medicines like methadone effectively, she said.

But many do not. In one study of 22 prisons and six county jails, one-third of pregnant people with opioid use disorder were not given medication-assisted treatment, and of those who were, very few initiated it in custody. In another study where Sufrin’s research team conducted interviews with opioid treatment providers with pregnant patients in custody, many reported that their local jail did not offer medication-assisted treatment to incarcerated pregnant people.

“In many cases, there is a lot of negative stigma toward not only patients but also the medications, where people assume it’s just substituting one drug for another,” Sufrin told Salon in a phone interview. “Sometimes people who work in jails just don’t believe this is an appropriate treatment and they don’t want any opioids in their jail — even if it is methadone or buprenorphine treatment.”

Abortion access while incarcerated is also limited. One study Sufrin conducted found half of states allowed women who were incarcerated to have abortions in the first and second trimesters, but 14% did not allow them at all. Two-thirds of the prisons that did allow abortions also required the woman to pay.

Prisons are the only place in the U.S. where people are guaranteed health care due to a 1976 decision handed down in the court case Estelle v. Gamble. For Shanya and Leslie, prenatal care and addiction treatment were provided once they were transferred from jail to prison, they said.

Some states, like California and Maryland, do specifically have legislation in place requiring screening and treatment for substance use disorder in jails and prisons. But they are the minority: According to a 2023 study, 43 states had at least one statute related to pregnant and postpartum people who were incarcerated, while seven had statutes related to substance use disorder screening and treatment.

In February, U.S. Senator Jon Ossoff introduced a bill that would require states to report information about pregnancy care and outcomes for people who are incarcerated after an investigation from his office last year found women in Georgia had given birth on their own, been shackled around their stomachs, and were forced to undergo C-sections against their will, according to a statement from his office.

The U.S. Department of Justice is also expected to release results from a survey of pregnant people who are incarcerated this year after a 2024 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that "comprehensive national data on pregnant women incarcerated in state prisons and local jails do not exist.”

As it stands, the U.S. Department of Corrections and the Federal Bureau of Prisons both have dedicated medical branches to oversee health care in the carceral system, but there are no external agencies or committees to ensure standards are met, Sufrin said.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

“That constitutional requirement never came with any required set of health care services or standards or systems of oversight, and so what you get is total variability,” Sufrin said. “Some facilities do provide a reasonable measure of comprehensive pregnancy care, including access to treatment for opioid use disorder, but many do not, and there is no systematic established oversight of prisons and jails in the United States when it comes to health care, including pregnancy care.”

"Once there is no more fetus and the woman is no longer pregnant, their interest evaporates."

In some states, like Tennessee and North Carolina, pregnant people can be sent to prison legally through “safekeeper” laws before they are convicted if it is deemed that there is not adequate medical care in their jails. Although these laws were designed to provide care to inmates who need it, they effectively take away a person’s freedom, Jones said.

“The other way to think about it is, doesn't that jail that has now taken away a person's liberty have an obligation to uphold the human right to provide adequate medical care?” Jones said. “Basically, you are in prison because of your pregnancy.”

Often, pregnant people are incarcerated because of charges related to their substance use. In a report by Pregnancy Justice released last year, nearly all of 210 cases in which a pregnant woman was prosecuted involved substance use. Ninety percent of charges were for some form of child abuse, neglect or endangerment wile 86% of cases did not require prosecutors to find evidence of harm to the fetus — meaning it was up to the judge to decide if an embryo was being put at risk due to substance use.

This particularly impacts women of color, who are prosecuted at higher rates for drug use despite using the same amount of drugs as white women. The Pregnancy Justice report showed that low-income women were particularly targeted by pregnancy criminalization as well. And in 16 cases, women were charged in connection with using medication-assisted treatment to treat addiction, said Dana Sussman, senior vice president of Pregnancy Justice.

“There have been reports about people who are following their physician’s guidance… and still facing family policing investigations or child welfare investigations,” Sussman told Salon in a video call. “The systems are stacked against you if you need to continue on medication-assisted treatment.”

While pregnant women can sometimes be prosecuted more strictly because of their pregnancy, the level of care they receive also seems to be tied in many cases to their pregnancy, Sussman said. For example, access to medication-assisted treatment is often removed once pregnant people give birth, even though this is a particularly vulnerable time for relapse, overdose and death.

In Sufrin’s study, two-thirds of prisons and three-quarters of jails that did provide medication-assisted treatment to pregnant people discontinued it after mothers gave birth. This was something that providers reported as well.

“They recognize that [medications for opioid use disorder] support the health of the fetus, but once there is no more fetus and the woman is no longer pregnant, their interest evaporates,” Sussman said. “They don’t actually care about the woman’s survival or the woman’s health.”

Overdose has been identified as one of the leading causes of death in the postpartum period, with mortality rates increasing by more than 80% between 2017 and 2020. Although medication-assisted treatment can reduce the risk of overdose by up to 60%, only about one-third of women with substance use disorders receive this care postpartum. This is especially important for new mothers who are being released from jail or prison, which is also a time that has been associated with an increased risk of overdose.

“[Pregnancy] is a real opportunity for intervention,” Sussman said. “But if they can't find [medication-assisted treatment] or they're cut off immediately after pregnancy, then they are set up to fail.”

It can be difficult for women to get this care postpartum due to bureaucratic barriers, said Sara Brown, director of the Pregnant and Parenting Women with Children program at the Nexus Family Recovery Center in Texas, which provides services to pregnant and postpartum women with substance use.

Brown said one of her clients, for example, doesn’t have transportation but has to travel to another city just to receive medication-assisted treatment. New mothers also have to juggle finding and paying for childcare during this time, as well as making it to probation or parole appointments and meeting requirements from Child Protective Services — all while experiencing the typical roller coaster of an experience it is to become a new mother.

“It’s hard for them because they have court dates and they're talking to their attorneys while trying to stay sober, be a mom, and focus on their pregnancy,” said Lindsay Malhotra, director of outpatient services at Nexus.

Although CPS is a social service agency, it has a lot of overlap with the criminal justice system. Because many women fear having their children taken away due to substance use, they may not disclose their use to their providers, who are mandated to report them. This serves as another barrier separating them from treatment.

“I’ve had patients tell me they tried to hide their pregnancy so that their methadone provider didn’t know because they were worried they were going to be turned away,” Jones said. “We have certainly had patients come to our OB clinic saying they were ‘fired’ by their addiction treatment provider because they were scared that they were pregnant."

While CPS can protect children from harmful situations, children who experienced interactions with CPS have an increased risk of incarceration, substance use and having CPS involved with their own children later in life. Having a parent who is incarcerated is itself an “adverse childhood experience,” (ACE) a label used by researchers to define a traumatic experience that has lasting health consequences, including an increased risk for substance use.

All of this together creates a system in which trauma related to substance use and incarceration perpetuates in future generations, said Dr. Mishka Terplan, an OB-GYN and addiction medicine doctor at the Friends Research Institute.

“Children are being raised, either through [the criminal justice system] or child welfare, separate from their parents, and accumulate ACEs,” Terplan told Salon in a phone interview. “These lead to addiction which leads to people being incarcerated, and it’s like a feedback loop.”

Sources say this system is likely playing a role in the maternal and infant mortality crisis, although getting a complete picture of the role that incarceration and substance use plays in this crisis is once again challenging because it relies on states, which do not always report. For example, Texas skipped reviewing the first two years of maternal mortality data after implementing its near-total abortion ban. In November, Georgia dismissed all 32 members of its committee that reviews maternal deaths after investigative reporters linked two maternal deaths to the state’s six-week abortion ban.

Jessica, a new mother that was released from jail after spending seven months of her pregnancy there waiting for a court date, is currently staying at Nexus Family Recovery Center, where she is connected to addiction treatment services including medication-assisted treatment. Yet of more than 11,000 centers across the country designed to care for pregnant and postpartum women, fewer than half administer medication-assisted treatment. Those that do are not enough to meet the demand; Nexus has a waitlist of about 10 women, Brown said.

“We are already seeing programs shut down this year,” Brown told Salon in a phone interview. “[These are programs] that helped people prepare for career opportunities, prepping them for interviews, and all of those things.”

Although Jessica will spend the next several months at Nexus, where her treatment is covered by her insurance, she worries about how she will afford and manage all of the requirements the courts and her treatment demand when she finishes her time there. She has already had to pay thousands of dollars in restitution fees.

“I felt like this was kind of setting me up for failure,” Jessica, who is using her first name only for privacy reasons, told Salon in a phone interview. “One of my concerns is how this is all going to play out, but I am just taking it one day at a time.”

Like Shanya and Leslie, in North Carolina, Jessica was connected to the pregnancy and postpartum program at Nexus that provides addiction treatment while she was incarcerated.

“I was ready to get my life together,” Jessica said. “I needed help, and I knew Nexus had great resources, so I decided to give it a try.”

Now, all three women have had their babies and remain in treatment. Jessica’s son is doing well, and at nine-weeks old, Leslie’s daughter is hitting all of the growth milestones she should. Shanya’s son just started daycare at the center this week.

“If I hadn't come here, I don't think that I would be sober, and I would probably still be on the streets,” Shanya said. “Being in this program has done wonders for me and my son.”

Read more

about drug policy

Shares