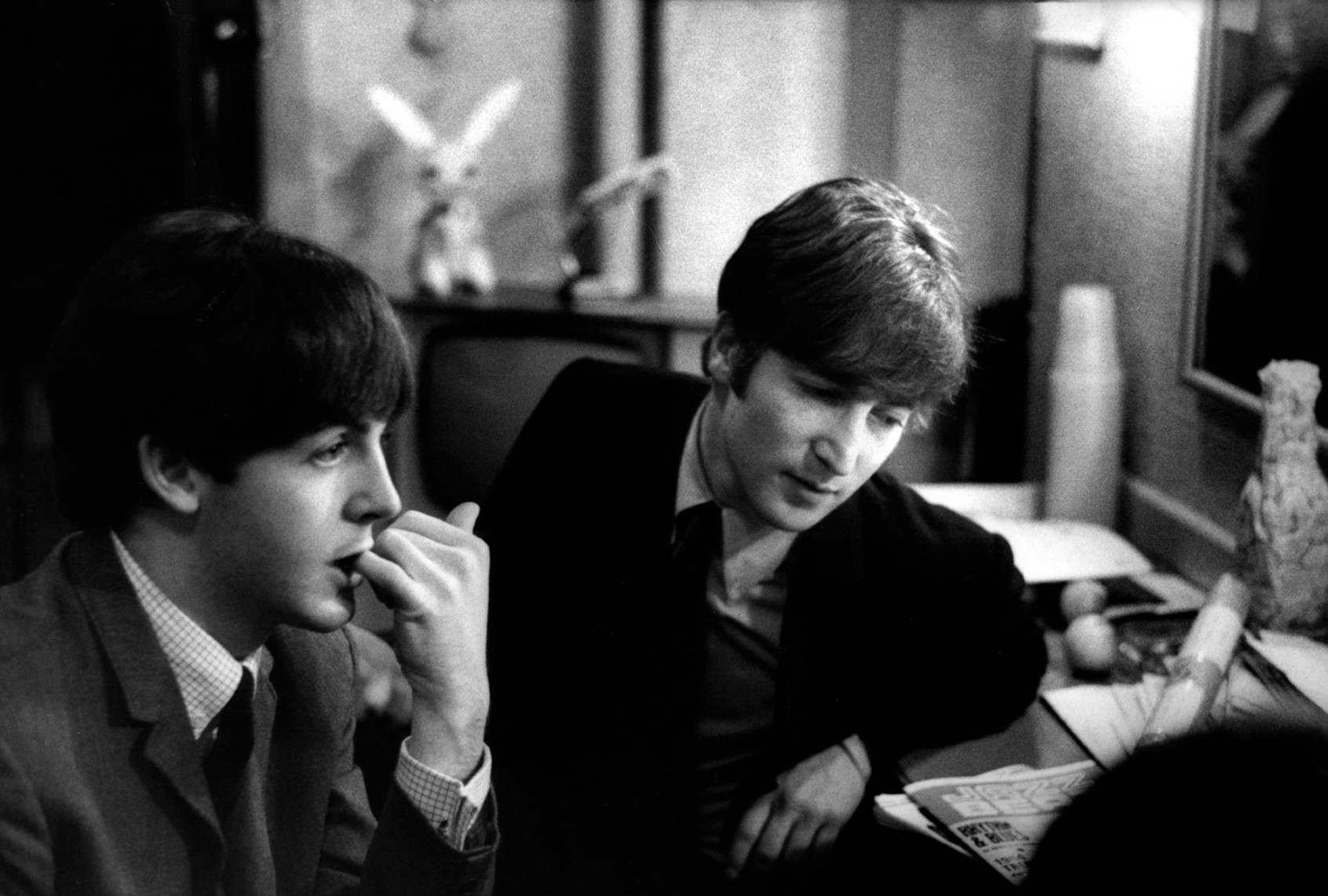

When it comes to elevating our understanding of The Beatles, Ian Leslie’s new book "John & Paul: A Love Story in Songs" is a mixed bag. On the one hand, Leslie provides elegant readings of a host of Lennon and McCartney classics. But on the other, he romanticizes the legendary songwriting duo’s friendship out of proportion with the immutable facts of history.

Don’t get me wrong: I share Leslie’s impulse to wax nostalgically about "the act you've known for all these years." There’s a symmetry, a kind of eternal beauty to their mythos that is irresistible. From Lennon and McCartney’s famous meeting at a July 1957 village fête to The Beatles’ recorded corpus itself—an incredible 12 studio albums committed to tape in just seven years—there is an inherent grace and power to their story.

And then it was suddenly and ineffably over with the magisterial swan song of "Abbey Road" (1969). When the album proper came to a close with “The End,” the Fabs, it turns out, meant business. While their disbandment was the stuff of brute, emotional turmoil played out in highly public fashion for much of the first half of the 1970s, their legacy remains pure and unsullied by halfhearted attempts at reunion.

In its finest moments, "John & Paul" deftly captures the sublimity and heartbreak of The Beatles’ story. Leslie traces Lennon and McCartney’s friendship from its wide-eyed, teenaged origins through its tragic denouement. It is absolutely true, as Leslie chronicles in painstaking fashion, that Lennon and McCartney shared a closeness during their formative years through The Beatles’ final months as a working rock ‘n’ roll band. This is not a matter that is under dispute among the vast majority of writers and thinkers about The Beatles.

Even still, Leslie feels compelled to write, “there are several reasons why we get Lennon and McCartney so wrong, but one is that we have trouble thinking about intimate male friendships. We’re used to the idea of men being good friends, or fierce competitors, or sometimes both. We’re used to the idea, these days, of homosexual love. We’re thrown by a relationship that isn’t sexual but is romantic: a friendship that may have an erotic or physical component to it, but doesn’t involve sex.”

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

I believe that Leslie’s contention is, at best, a straw-man argument. To my knowledge, no one is suggesting that we have a cultural dis-ease with the intense closeness of the Lennon-McCartney friendship. There is little doubt that they loved each other deeply, that they shared an extraordinary experience and, together, piloted popular music’s most influential and impactful musical fusion.

But in endeavoring to couch their relationship in such platonic romantic terms, which seems to exist at the heart of his agenda, Leslie loses his grasp on the painful reality of the duo’s intimacy. Whatever closeness they shared had dissipated by at least 1977. Perhaps they were understandably exhausted by the trauma and infighting of The Beatles’ breakup. Or were they coming to the conclusion, as so many of us do in adulthood, that their friendship, while tender-hearted and creatively prolific, had simply entered a different and far less intimate phase?

There is little doubt that they loved each other deeply, that they shared an extraordinary experience and, together, piloted popular music’s most influential and impactful musical fusion.

As Allan Kozinn and Adrian Sinclair’s second volume of "The McCartney Legacy" makes clear, John and Paul had all but mothballed their friendship during their latter years. After Lennon’s December 1980 assassination, McCartney expressed relief that “the last phone conversation I ever had with him was really great, and we didn’t have any kind of blowup. It could have easily been one of the other phone calls when we blew up at each other and slammed the phone down.” It would be facile and easy to argue that this level of emotion is characteristic of their “intimate male friendship” and their shared passion run amok. But it is equally plausible that like so many friendships that have grown long in the tooth, they had become fed up with fighting the old battles, that they had developed new and more fulfilling relationships with their young families.

But the bitter truth is that we’ll never know, that all of this is the stuff of conjecture. Witness Beatles fans’ collective romanticizing about “Now and Then,” The Threetles’ posthumous 2023 UK chart-topper, as Lennon’s late 1970s ode to his friendship with McCartney. I get it. I really do. I, too, am drawn by this ineluctable desire to become sentimental about John and Paul. After all, they concocted a rich and deeply affecting songbook that never fails to rouse my inspiration and, truly, to heighten the experience of simply being alive.

We need your help to stay independent

This is their legacy, and when Leslie writes movingly about The Beatles’ music, his book genuinely sings. But at other times, Leslie seems to be overreaching in his quest to ascribe something greater to their relationship, a friendship that was cruelly and tragically cut short. In his first public statement after Lennon’s senseless murder, George Harrison remarked that “to rob life is the ultimate robbery.” To be sure, an assassin’s bullets robbed Lennon and McCartney of any hope for establishing a new and abiding friendship in middle age. But as I noted above, we’ll never know. Such is the insidious nature of taking another person’s life. To suggest anything else is to dabble in idle wish-fulfillment.

As I observed at the outset, I understand Leslie’s impulses implicitly. I, too, wish that things were different, that the two men who acted as the fount for the most significant art in my life had been able to pass gently into that good night. But I am heartened by Lennon’s words when he pointed out, in a moment of great optimism, that people needed to give up their fixation on The Beatles’ relationship and the near-constant clamoring for the bandmates’ reunion and concentrate their energies on the music itself. “It’s only a rock group that split up,” said Lennon. “It’s nothing important. You have all these old records if you want to reminisce.” He was right then, and he’s right now. It’s the music, as opposed to our lingering desires to romanticize an unfinished past, that matters.

Read more

about Lennon and McCartney