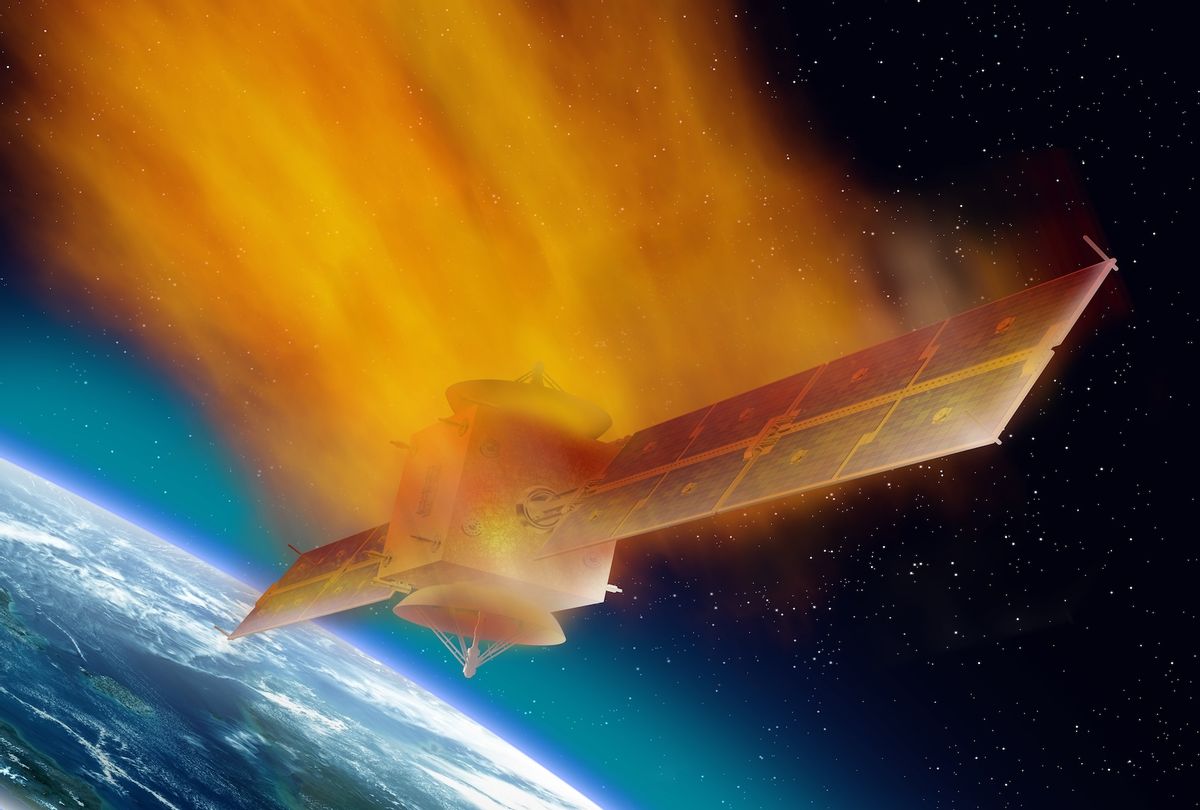

In the early morning hours of February 19, 2025, a bright object streaked through the skies above western Europe. The mysterious, flaming hunk of metal traveled for several hours before smashing into a warehouse in the Polish village of Komorniki.

“I felt surprised but also a little scared,” Adam Borucki, the warehouse’s owner, told the BBC in an interview. “But ultimately, I’m glad no one was hurt.” After inspection by local authorities and the Polish space agency, officials determined the object’s identity: a piece of debris from a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket that had re-entered the atmosphere.

This isn’t the first time space junk has crashed to Earth. In December 2024, a half-ton piece of space debris flattened trees in a remote village in Kenya. Earlier that same year, a chunk of rocket landed on a North Carolina roof and a discarded space station battery pelted property in Florida. In 2023, fragments of carbon fiber and metal rained down on a Ugandan home.

Falling space junk is starting to become a real problem. So how worried should you be about it landing on you?

“The chance of you getting hit is absolutely minuscule,” Ewan Wright, a space sustainability researcher at the University of British Columbia, told Salon. “But across the whole world, the chances of somebody getting hit is rising to a level where we actually have some concerns about it.”

Individually, a person’s estimated chance of being struck by space debris is something like one in a trillion. But the odds of debris striking someone on Earth is closer to one in 10,000, as Wright and his colleagues calculated in a 2022 paper published in Nature Astronomy. In fact, in 2002, a young boy in China became the first person to ever be reportedly injured by a piece of a falling rocket (he survived with only minor injuries.)

"The chances of somebody getting hit is rising to a level where we actually have some concerns about it."

Of course, a direct bodily hit isn’t the only hazard of falling space junk. There is a chance that debris could reenter commercial or federal airspace and pose a danger to aircraft, for example. Experts estimate that the world’s busiest airports have about a 26% chance each year of being affected by uncontrolled re-entries. Some countries have already had to deal with this — in 2022, Spain and France closed parts of their airspace to avoid a falling Chinese Long March 5B rocket. And such risks, however small, are growing.

“The problem we’re facing is that the number of launches is continuing to increase,” says Aaron Boley, an astronomer at the University of British Columbia.

That pace shows no sign of slowing down. 2025 is expected to see a record-breaking number of launches, as a new international space race heats up and companies like Starlink, a subsidiary of SpaceX, rush to put internet satellite “megaconstellations” in place.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

Another issue is that climate change is messing with LEO, according to research published last month in Nature Sustainability. As carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gasses build up in the dense lower atmosphere, they absorb heat and keep it trapped there. But in the thin upper atmosphere, carbon dioxide can’t hang onto its extra heat. This means the upper atmosphere ends up contracting “like a balloon being placed in liquid helium,” Matthew Brown, a systems engineer at the University of Birmingham in the U.K., explained to Salon.

As a result, objects in this region are now experiencing less drag than they did decades ago — which means they are staying up longer, and fewer are completely burning up on reentry. More objects in orbit means more debris with the potential to leave come down unexpectedly.

A crowded upper atmosphere could also trigger a phenomenon called “Kessler syndrome.” In this scenario, pieces of debris crash into one another, fracture into smaller pieces, which then crash into more junk or even functional spacecraft, creating a chain reaction. This cascade goes on until LEO is filled with shrapnel zipping around at intense speed.

“This runaway effect could render entire orbits unusable,” Michele Scaraggi and Rajat Srivastava of the University of Salento in Italy told Salon in an email interview.

So what can we do to address the hazards posed by space debris? Some space agencies and private companies have begun designing their craft to ablate — break apart and burn up — in the atmosphere at the end of their life, an approach called “design for demise.” While great in theory, the issue is that optimal design is difficult to predict, especially given Earth’s changing atmospheric composition. “If they’re wrong, then they have 10,000s of pieces of space debris that are going to come down and hit the ground,” says Wright.

SpaceX, for instance, designs most of its Starlink satellites to disintegrate upon reentry. But some of those de-orbited satellites don’t seem to fully ablate or burn up. One landed on a farm in Saskatchewan, Canada last year. And even craft that burn up completely might cause harm; researchers are concerned that the aerosolized metal could be damaging the ozone layer, reversing years of progress in protecting it.

We need your help to stay independent

Another option is managed re-entry. The idea behind this is to guide large pieces of re-orbiting debris to a predetermined location, usually a spot in the Pacific Ocean. Managed re-entry is often used for large craft on short missions, but it can be very difficult to arrange for long-term missions.

Some agencies are also making plans to remove debris directly from LEO. Proposed approaches include snatching debris with a robotic arm, scooping it up with giant nets, attracting it with magnets and spearing it with harpoons. Though there are currently no removal efforts active in orbit, the European Space Agency has plans to launch its first clean-up mission, called ClearSpace-1, in 2028. “These initiatives are critical stepping stones,” Scaraggi and Srivastava said.

Finally, there is ground-based emergency management. Counties in a few U.S. states, including those with rocket launch sites like California, Texas and Florida, have drafted emergency response plans for falling space debris. However, this is an area that needs to be developed much further, both in the U.S. and globally.

As climate change intensifies and new launches clutter our planet’s orbit, we’re almost certainly going to see more debris crash back to Earth. Humanity is going to need to come up with ways to prevent these re-entries from becoming casualties. This will involve, perhaps, being more intentional and strategic about how we send things into space.

“We definitely want to ensure that we have continued and safe access to outer space,” Boley says. “But the promise of prosperity is not permission for recklessness.”

Shares