We often remember movies, years and decades later, for reasons just and unfair.

Just: "American Psycho," on its 25th anniversary, stands as the wicked feminist satire of 1980s greed and male vanity its Canadian director and co-screenwriter Mary Harron imagined, instead of the vile misogynist fantasy Gloria Steinem crusaded against during pre-production.

Unfair: Scenes like protagonist Patrick Bateman's murder of a colleague set to the Huey Lewis song "Hip to Be Square" carry the movie into the future mostly as social media parodies. The character of Bateman himself, a hollow yuppie in an inferno of his own making, lives in our present climate of "hustle" and toxic masculinity as a role model (by more than one real-life murderer) rather than a warning. The cultural headspace of "American Psycho" memes and bad faith takeaways make it too easy to forget who saw it as more than blood and business cards in the first place.

The cultural headspace of "American Psycho" memes and bad faith takeaways make it too easy to forget who saw it as more than blood and business cards in the first place.

Praise due then to the visionary work of Harron, who had, a few years before, begun her directing career with "I Shot Andy Warhol," another modern classic about the dangerously close relationship of self-mythologizing and violence. It was Harron's sense of Bret Easton Ellis' 1991 novel of stockbroker/serial killer Bateman as dark comedy playing on the emptiness of greed and male violence born of self-hatred that earned the adaptation its critical acclaim. It was the world Harron and her creative team built for "American Psycho" that made us in the audience remember it so clearly a quarter century later.

Harron has directed six films, the majority of which concern the real-life famous (2005's "The Notorious Bettie Page") and infamous (2018's "Charlie Says," about the women of Charles Manson's cult). It is "American Psycho," a fictional tale of infamy inside the protagonist's mind and cruelly appointed apartment, that showed Harron as a master visual interpreter of popular literature as well as popular history. And as the filmmaker responsible for one the great sophomore outtings of 21st century cinema.

The novel "American Psycho" was published in 1991 and takes place in 1987. You filmed it almost a decade later, and it seems like your directing also referenced earlier moments in film history — the '50s-style title sequence Saul Bass was famous for and echoes of Film Noir and Hitchcock.

My initial response when (Producer) Ed Pressman asked me to write a script based on it was that you could do a film set in the '80s, and times had changed enough for it to be a period film. But that was never my absolute goal. Although it's funny at the time, some of the reviews said, “We all know about the '80s. What is new about this?” And to me, I was surprised because it was never about that. It was about the society now as much as it was the society 10, 15 years before.

I've done a lot of period films. Almost all my films, except for maybe one, have been period. So I have a lot of ideas about how to recreate a period. And one of them is you never make everything in the room from 1986. Even wealthy people have things from different eras, and certainly, people who are less wealthy will definitely have older stuff.

Gideon Ponte, who was the production designer, said, "It's really kind of early '90s." There are certain little '80s tropes in the restaurants and things, but Bateman’s apartment could be early '90s with that kind of minimalist (look).

We are looking at the past, but not one specific moment in the past. Like a series of pasts stacked on one another

Yes.

"American Psycho" is a black comedy and is deeply satirical. Did you accomplish the look of that using a kind of heightened reality, or did you shoot it very literally and let the satire and the comedy be in response to how flat and literal the visuals are?

Honestly, we never had those conversations. I think I find the style while I'm doing it.

When I was trying to find a director of photography, my husband said, “Why don't you try Andrzej Sekula?” because Andrzej had just done "Pulp Fiction" and the wide angles, the crispness, the certain black comedy, could be right for "American Psycho," which I think it really was. So when I met with Andrzej . . . I don't think I ever said, "It's not quite real. It’s real. The comedy will come this way…” The comedy was going to be how I directed the actors. The thing Andrzej and I were very clear on was that it was deep focus, very crisp, which gave it a kind of hyperreal quality.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

I realized after making it that it was hard for me to explain to people that it was not a realistic film. but it was quasi-realistic, and there were moments it would be played fairly realistically, like Jean's character (Chloë Sevigny, who plays Patrick Bateman's secretary) is a realistic person. But there's elements that are very heightened, there's elements of Christian's performance that's extremely stylized, but it all has to work in this world.

I don't think I would ever sit down when a film was starting and say, “This is what we're doing. this is how it's going to go, it’s this place between realism, or it's this place between poetry and whatever” The exciting thing is to find it as you do it and you'll know as you're working your way through it. And what is most exciting is if you don't entirely know and you're finding it as you go.

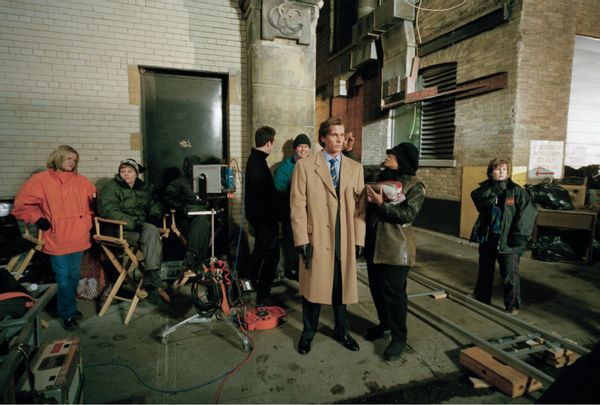

Christian Bale on the set of "American Psycho," based on the novel by Bret Easton Ellis and directed by Mary Harron. (Eric Robert/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images)I'm so glad we started talking about your creative partnership with Sekula because so much of the making of "American Psycho" seems to be the story of one and one equals three. You and Sekula, you and co-writer Guinevere Turner, you and Christian Bale. These creative duos all seem to add up to what made this movie special.

Christian Bale on the set of "American Psycho," based on the novel by Bret Easton Ellis and directed by Mary Harron. (Eric Robert/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images)I'm so glad we started talking about your creative partnership with Sekula because so much of the making of "American Psycho" seems to be the story of one and one equals three. You and Sekula, you and co-writer Guinevere Turner, you and Christian Bale. These creative duos all seem to add up to what made this movie special.

The person I had more theoretical conversations with was Gideon because we're such good friends, but also because I am also obsessed with production design, and he reminded me recently that what I told him about Bateman's apartment was, "It's where extremely straight and extremely gay meet in the middle."

That's perfect.

I don't even remember saying that, but he obviously remembered it.

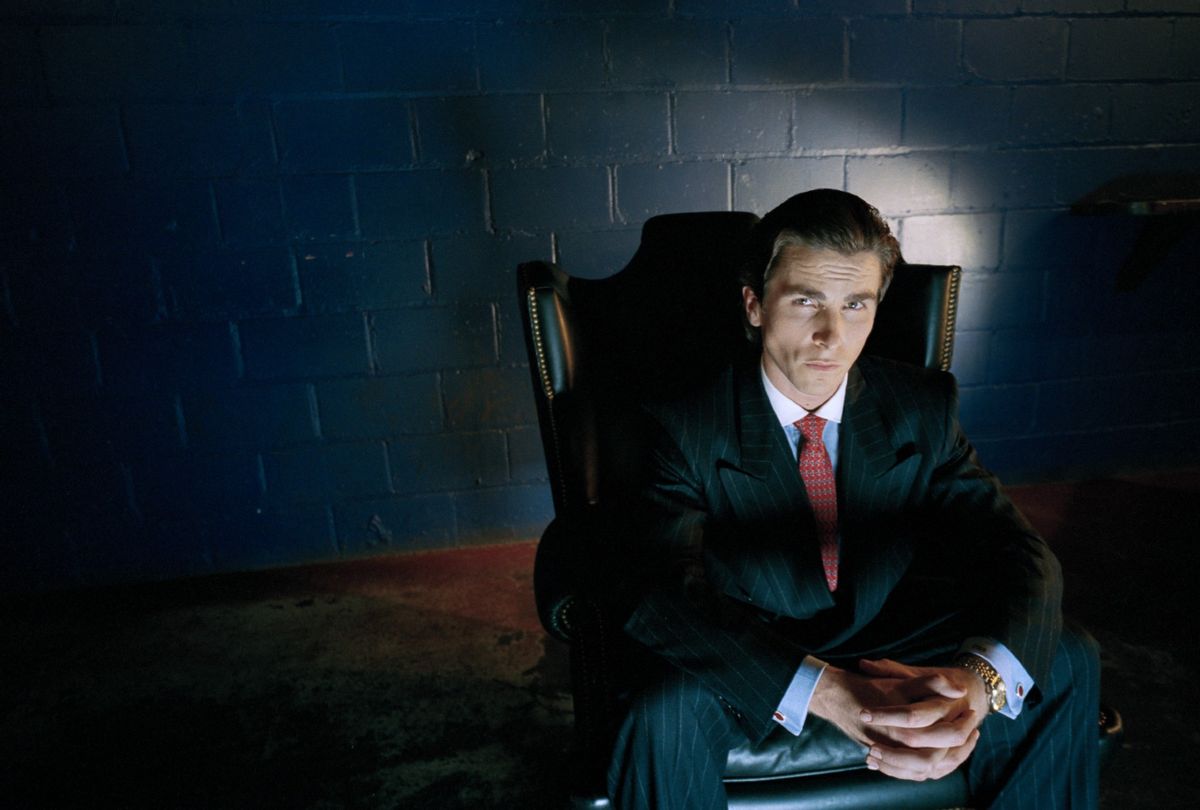

I gave him outlines like a stainless steel kitchen or white apartment. I want it to look like Architectural Digest. Nothing personal anywhere. No photos, no memorabilia, nothing. And that was very important so that you wouldn't sort of personalize Bateman. He becomes more an abstraction of wealth and predatoriness.

I think my favorite bit of production design in the whole movie is in the apartment, the oversized light box on the wall of what looks like a suit containing no man.

I remember Gideon, actually, we were shooting in another part of the set, and he asked me to come in and look, and he says, "You may think this is too on the nose. Just preparing you. I just want you to look at it and see if you think it works." And I walked in and thought, yeah, it's perfect.

We need your help to stay independent

It's "on the nose" because, of course, there is a recurring theme in the movie that Bateman is not really there. The other characters keep calling him by the wrong name, and he talks about his nonexistence in voiceovers at both the beginning and end of the movie. What does the character of Bateman get out of saying that about himself? Because he doesn't seem to be a person or an entity who does anything without ego.

If you have him doing it at the beginning, then you know that this is his story and his version of events. What does he get from it? I don't know because, in some ways, it's the voiceover absolutely from the book.

I think a writer like Bret — in this case, he had written this voiceover — gives the protagonist more self-knowledge than they have, maybe more insight or more eloquence . . . but it's also stating directly something that he undoubtedly must feel about himself, that he's always in panic because he doesn't know who he is or what (he is), there's no core to him. So, it's articulating that.

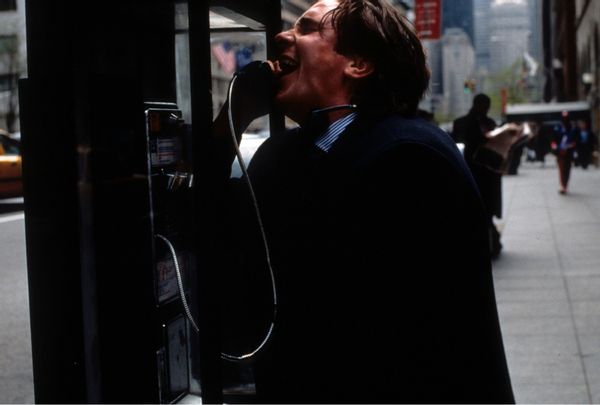

Christian Bale in "American Psycho" (Lion's Gate/Getty Images)Yeah. It seems to be an idea that the movie swirls around, which is that the main character is not really a person, but an empty body that we project the ideas of the film through.

Christian Bale in "American Psycho" (Lion's Gate/Getty Images)Yeah. It seems to be an idea that the movie swirls around, which is that the main character is not really a person, but an empty body that we project the ideas of the film through.

Although there's also all the rage and anger and panic. So he's not just empty. There's a sort of roiling rage and explosion inside him that erupts in the violence. So there's also the panic of feeling like nothing.

You have to have something for the idea of Bateman to push against. I feel like the movie is unfairly criticized for the flatness of the female characters or the actresses' performances, and I think those are the performances that give the movie its humanity.

I don't know where that comes from. Because Chloë (Sevigney) gives a beautiful vulnerable subtle performance and Cara Seymour (as late-in-the-film Bateman victim Christie) is just a great actress who does so much with very few lines, but you're totally aware all the way through that she's hiding her fear and her panic and as she realizes that she's made a very bad decision coming here, and you feel her vulnerability and you long for her to escape

I like very subtle acting. On the other hand, I love Christian's performance, which is very big and almost slapstick at times but is so perfectly controlled. Somehow they all fit in the same space. Just because Chloë and Cara and the others are doing more naturalism, that doesn't mean they're not good performances.

And your co-writer, Turner, appearing on screen as a character a hundred miles away from the college student she played in "Go Fish," the movie that made her famous a few years before.

Poor Guinevere! She will never forgive me for making her lie on the bathroom floor covered in blood. Guinevere loves '30s comedy. She's doing a sort of dry '30s comedy performance about rich people.

Can we talk about your writing partnership? You two were working together on the script of what became "The Notorious Bettie Page" when "American Psycho" came into your life. What kind of evolution did your creative partnership go through on this project?

When the idea to do "American Psycho" came along, I was working on it on my own — the concept of it, which is always something I kind of want to do . . . just sit with the material for a while. I always come up with the first and the last scene in a movie but not what's in-between. But really early on, I thought, I don't like to write on my own.

"How could anyone tell us what is misogynist? Do you think we don't know what's misogynist?"

Guinevere is really great at dialogue, which I’m not. I like to do structure, really, and concept and world-building. Guinevere would really get this. We would be disturbed by the same things.

Guinevere had just done "Go Fish" and I’d just done "I Shot Andy Warhol" and I felt like together we would be very strong, because how could anyone tell us what is misogynist? Do you think we don't know what's misogynist? We are kind of in the vanguard; at that point, I felt we had both made our statements, in terms of hers being a lesbian film and mine in terms of that it’s also a lesbian (film), but also radical feminist. I think that we could just go in with a lot of confidence, which I think a man would not have had. He would be worried about how he would appear, or second guess, and we just felt like our instincts on this are good.

"American Psycho" is very much about male vanity. I'd love to hear some of the choices or conversations you and Turner had about this.

We were very amused by Bret, being gay, that he had picked up on what was very gay in macho culture. The obsession with looks and fitness and the kind of b***hiness, the way they are criticizing each other. Bret had spotted this and really had an insight into that.

The direction I gave to actors was really moment by moment. Christian came up with this thing during the three-way sex scene when we were rehearsing it, of looking in the mirror and posing. That was his idea and it was really funny.

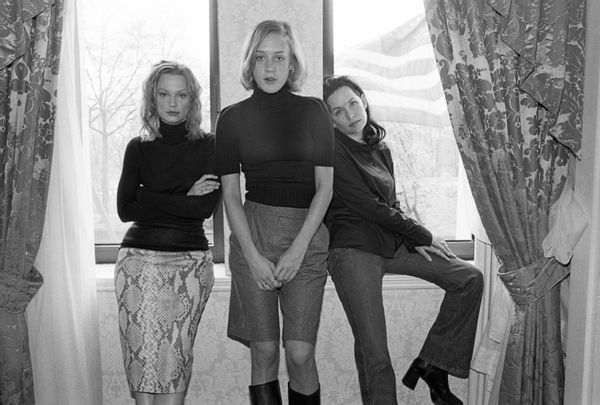

Guinevere Turner, Samantha Mathis and Chloë Sevigny pose for a portrait to promote "American Psycho" on April 11, 2000, in New York City, New York. (Catherine McGann/Getty Images)You fought hard to cast Bale as Bateman, and you guys were kind of on an island of two people who believed that you had the right idea of how this movie could be made and that you were the right people to make it.

Guinevere Turner, Samantha Mathis and Chloë Sevigny pose for a portrait to promote "American Psycho" on April 11, 2000, in New York City, New York. (Catherine McGann/Getty Images)You fought hard to cast Bale as Bateman, and you guys were kind of on an island of two people who believed that you had the right idea of how this movie could be made and that you were the right people to make it.

We both got fired off the movie, and I put a lot on the line for casting him, and I remember thinking before we started shooting, “God, I hope I'm right about this." It was a big leap, but really from the moment we first talked about it I could see that, as with Guinevere, that we had the same sense of humor about it, that he thought it was funny.

I had met with a number of young actors who thought Bateman was cool. No, no, no, he's dorky. He's absurd. I wanted an actor who could see the ridiculousness of it and could have a distance from it.

(Leonardo) DiCaprio was interested in doing it, and I immediately thought that it was a terrible idea for many reasons.

"I had met with a number of young actors who thought Bateman was cool. No, no, no, he's dorky."

One of the things about the movie is that a lot of people mistake Bateman for someone else, and you couldn't cast six different DiCaprio look-alikes. He's very distinctive looking.

I knew it was a terrible idea because he had just come off "Titanic," and this is someone who's the hero and the heartthrob of millions of adolescent girls. You cannot cast him as Bateman. It's so wrong. I knew that this film would never work if I didn't have absolute control over the tone of it. It had to be really really delicately handled because you're dealing with controversial material, but you're also threading a way through satire and horror and fear and real pain and just many, many things. And you have to just get the balance really right. It's not easy to do this kind of tone. I thought I was off the movie forever until they invited me back.

Up to "American Psycho," Bale had played mostly boys and teenagers. Was his transition into adult roles part of what made him right for Bateman? A boy play-acting at being a man?

No, not particularly. I mean, he came and read for me, and it was based on who he was. I felt that he had a quality that was similar to Lili Taylor (star of Harron's previous film, "I Shot Andy Warhol.") There was something sort of unfathomable about them, in a way that there was something very deep in them as actors. When they're in close-ups on screen, you would never get to the bottom of them.

The way he's very striking and anonymous at the same time.

Exactly. It was based on that.

So many of your movies are about famous and infamous people, and really any one of them could be held up as a mirror of who we are now because, unfortunately, fame and infamy and the danger of self-mythologizing never go away. And yet, I think you are quite right when you say this is going to be the Mary Harron film that will continually be cited as the most prism-like of the times we live in. What is it like for you as an artist?

There's a point where you don't want to think about yourself too much in that way.

"I think 'American Psycho' is really about a kind of capitalism, a kind of destructive, greedy force that we're still living in. In fact, it's worse now."

I love "Charlie Says." I'm really proud of that movie, and I think that actually has something to say because we are living in a cult, a Republican cult right now. And I feel like Guinevere and I really explored some things there about how people give up their autonomy and their conscience and all that, but it's a tough movie, and "American Psycho" can also be fun to watch even though it's violent.

I think "American Psycho" is really about a kind of capitalism, a kind of destructive, greedy force that we're still living in. In fact, it's worse now. I honestly kind of thought it was in the past era, the Reagan '80s. I detested a lot of that, but honestly, it's kindergarten compared to what's happening now

There's been talk of a remake of "American Psycho." If you had the opportunity to adapt this same material now, rather than 25 years ago, how would you have approached it?

I can't think that way . . . because to me it's done, and that's what I did at the time. I like to move on, actually. I never do the same thing. There are obviously similar things in everything that I've done – but I kind of always want to do something different. I would never do a sequel to "American Psycho" or a remake; it wouldn't matter what you paid me.

Obviously you can't worry about this when making a movie, but I always wonder if directors have a moment of doubt when they look at the project and they say, “This part is designed to be a large set piece and there is a chance that 20 years from now this is all people will remember of this movie."

I mean, no, I don't think about that when I'm making something. You don't know what people are going to choose or what's going to become meme-able or whatever. I'm sort of tired of it, but I also think it's funny. I mean, I have to be more gracious about it, and you shouldn't have to be glad if anything really hits.

Yeah. I think shortly before he died, David Bowie said, "I've been doing this 40 years, and when I'm gone, people are going to say, "Ziggy Stardust" and "Let’s Dance."

Yes. Yes. Honestly, that'll be me as well. They'll just put "American Psycho," the Huey Lewis scene, his business card scene or whatever on my tombstone, and you have to kind of accept it. I'm sure a lot of people feel that way, but you're always trying to do something different, and you can be proud of things that you've done, and I am.

Shares