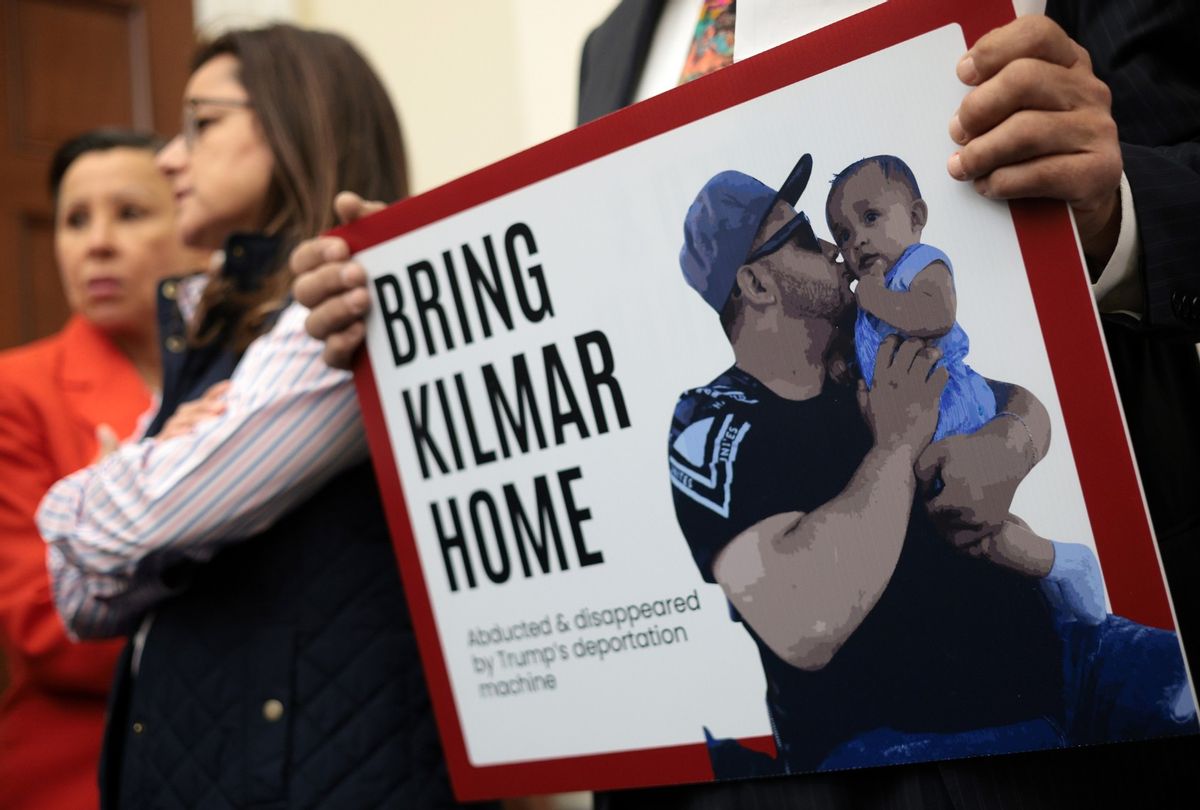

Tensions are roiling across the nation over the apparently mistaken deportation of a Maryland man to El Salvador and the Trump administration's refusal to bring him back to the United States, despite multiple court orders.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers arrested 29-year-old Kilmar Armando Abrego Garcia last month and included him in a deportation flight to his native El Salvador due to an admitted "administrative error." A federal district judge ruled April 4 that his deportation was "wholly lawless" and ordered the government to "facilitate" his release from a notorious mega prison in the Central American country and return to the U.S. The Supreme Court largely affirmed that ruling 9-0 last week, but the Trump administration has used some ambiguity present in the opinion to argue that it only has to clear any domestic obstacles to Abrego Garcia's return to the U.S.

On Wednesday, after multiple attempts to track the administration's progress by mandating daily status reports about their efforts to return Abrego Garcia, federal District Judge Paula Xinis ordered both sides to complete an expedited fact-finding period, including sworn depositions from the Trump administration officials, in two weeks.

"Defendants appear to have done nothing to aid in Abrego Garcia’s release from custody and return to the United States to “ensure that his case is handled as it would have been” but for Defendants’ wrongful expulsion of him," Xinis wrote in the order. "Thus, Defendants’ attempt to skirt this issue by redefining 'facilitate' runs contrary to law and logic."

The Department of Justice on Thursday asked Xinis to pause her Supreme Court-affirmed order to "facilitate" Abrego Garcia's return to the U.S. and asked the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals to either stay or vacate the district court orders.

Adam B. Cox, a professor of immigration law at New York University who also researches democracy and constitutional law, told Salon Wednesday that the government is deploying a "false and misleading" read of the Supreme Court order to justify its reluctance to proceed as mandated and retooling techniques for delaying the case that President Donald Trump's personal legal team wielded during his bevy of now-defunct legal challenges.

With a government that in both court and public statements appears disinterested in cooperating beyond the bare minimum in these immigration cases, the courts can no longer assume good faith, he argued.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What are you making of this mistaken deportation case and the Trump administration's approach to addressing the Supreme Court order that we saw [last] Thursday?

I'm not entirely sure what to make of it. The Supreme Court issued an order that itself included a little bit of ambiguity that obviously required that the government "facilitate" — that was the term the court used — Abrego Garcia's release from the prison in El Salvador. As you can see from the hearing [Tuesday], the government wants to characterize its reluctance to proceed with the questions that Judge Xinis has asked as though their reluctance is a debate over the meaning of the term "facilitate."

I think that is not a fair characterization of the Supreme Court order because, while 'facilitate' is a term that could have a couple of different meanings, the thing that the court unambiguously required the government to do — to facilitate — is Abrego Garcia's release from the prison. And the administration, as the judge noted [Tuesday], hasn't done anything to facilitate the release. It has pretended as though the Supreme Court's order said not that they had to facilitate his release from the prison, but instead that they only had to facilitate his re-entry into the United States. And those are two very different things. The court was clear about what the government was required to do, and they're kind of pretending that the order means something different from what it says.

That was actually one of my questions — just trying to make sense of how they're reading this ruling. As you mentioned, it was that ambiguity with respect to the "effectuate" term that has since been removed from Judge Xinis' order. But, at this point, what comes next? How does the court compel [action]?

Judge Xinis has said that, obviously, they have to facilitate his release. The Supreme Court has been clear and unanimous that the government has an obligation to facilitate his release. That's a starting point, and everything the government has said in court — and even more so in its public statements — has made clear that the government has not taken any steps. So it appears from all the public statements that there's been no steps taken to comply with the clear requirement of the Supreme Court orders.

But Judge Xinis, I think out of an abundance of caution — this is the way courts proceed — her view is, "Well, the first thing we need to do is develop a factual record so that I can determine conclusively whether or not you have taken any steps to comply with the order of the Supreme Court. It kind of doesn't look like it superficially" — that's what she told the government yesterday in the hearing — "but we're going to do discovery. You're going to have to produce documents that the plaintiff asked for, you're going to have to answer questions that they put to you, and you're going to have to present government witnesses that are going to have to testify under oath to answer questions about what the government has or hasn't done." So that's going to be the next step, and that's a step towards the court building a factual record in order to reach a decision about whether the government's complying with the court's order."

Going off of that process, if we still see this argument play out [and] depending on how the trial court will judge the situation, does that go through its own appellate process back up to the Supreme Court?

There's a bunch of ways that it could proceed. In an ordinary case, there's usually nothing appealable at this moment. This is obviously not an ordinary case. Ordinarily, a party that's unhappy with a judge ordering discovery and taking testimony would not be able to run to an appellate court and say, "You can't allow them to take testimony." That's just not how it works. You have to wait until the case is over, and the court's reached a judgment before you go and challenge that in the appellate court. But I do think it's possible in this case that one of two things could happen.

One is the government could run to the appellate courts right away, even before there's an effort by the court to hold the deposition or to demand answers to the questions that the plaintiffs are going to pose and say, "This lower court judge has no authority to tell we have to answer questions." They could try to do that. I'm skeptical that the appellate courts would agree with them. That would be a radical departure from kind of ordinary court procedure. So that's one path. The second path is the plaintiffs ask their questions, they provide a list of the people they want to testify, and then the government simply refuses to answer the questions or refuses to make their witnesses available. And if they do that, they're going to have to provide legal reasons for that.

We saw in the Alien Enemies Act case before Judge [James] Boasberg that the administration used a kind of broad assertion of the so-called state secrets privilege to try to avoid providing information to the court. Something like that's possible here. The administration could say, "We're invoking the state secrets privilege. We won't answer any of these questions. We won't make these witnesses available to the court." If that happens, then the court might simply draw negative inferences against the government on the basis of their refusal to participate, it could issue a contempt order, or the plaintiffs could try to seek appellate review of their state secrets assertion. So you have, again, a situation where somebody is trying to get the appellate courts involved, where we still don't have this record that the trial court judge is trying to create. That's the second possibility.

The third possibility, of course, is we actually get this record developed The government answers the questions in some way. Their witnesses testify, and then the district court judge is going to issue a decision. She's going to decide whether the government's in contempt or not, and if she finds them in contempt, I'm quite confident that they will attempt to appeal that contempt finding.

Obviously you don't have a crystal ball, but is there any of those possibilities that you think is more likely than not to play out here?

The second possibility, to me — that feels most likely. I don't know for sure. The government doesn't have to run to the appellate court today. It's hard to know what they would say today if they went to an appellate court and said, "Stop the judge in this from moving forward." I think they're more likely to proceed by refusing to participate, either partly or wholly, in this proceeding that the judge wants to run. Maybe they refuse to make some of their witnesses available or refuse to answer some of the questions, and then that's going to create a confrontation between the district court judge, whose position is, "I need to be able to develop evidence I need to be able to know what the facts are to resolve whether you're complying with this order," and the government, who I think is likely to say, "You don't actually have the right to the information that you think you need in order to decide whether we're complying with the government order because that stuff is protected for some reason."

In the Boasberg Alien Enemy Acts case, those initial assertions were vague. The same lawyer, by the way, Drew Ensign, appeared in both matters. He would say, "Oh, it's a foreign affairs matter. You can't." And as Boasberg noted, there's no foreign affairs exception to producing information in court. There's specific legal claims you can make, like state secrets. But the question is whether the government will actually be clear because I think one of the things that has not always been clear about in recent weeks is what the legal basis is it asserts for doing or not doing something. It'll tell the judge, "We're not going to answer your questions, but we actually haven't asserted a legal basis to not answer your questions." So that's going to be a challenge.

In the hearing before Xinis [Tuesday], at one point, when Judge Xinis mentioned the names of a couple potential witnesses — the people who filed the declarations on behalf of the government in court, one of them, whom is a senior DHS official, the other, who is the general counsel of Homeland Security — Ensign is like, "Well, I don't know about testimony from him." And Judge Xinis says to him, "What would be the problem with him testifying? Are you suggesting there might be some sort of attorney-client privilege?" And Ensign responded like, "Well, yes, that's what I'm thinking." And then as Xinis noted immediately, "You put him forward as an affiant," which is just a super standard and legal practice that you always want to be careful about having a lawyer serve as an affiant because, of course, they're also an attorney in the matter who is privy to conversations that are often protected by attorney-client privilege. The usual practice is you'd be reluctant to have someone who's a lawyer on a matter serve as an affiant. But once you do, well, the problem is is that opens them up to having to testify.

So these are the kind of fights we're likely to see in the coming days. And, obviously, I think the government's strategy is, in part, going to be to try to slow things down as much as possible. We saw that in the hearing [Tuesday] when, again, Drew Ensign said, when Judge Xinis raised the possibility of depositions, "I don't really know about the availability of my clients." And she said, "Well, I'm not super interested in that. This is important, so we're going to proceed quickly, and they're going to come available."

That reminds me a lot of the Trump legal team's approach to all of his former criminal or civil cases that we saw over the past few years: trying to slow things down but also having this obfuscation technique in terms of responding to the various court orders or mandates.

Yeah, exactly. I think that encapsulates Drew Ensign's argument in court yesterday and it brings us back to where started, where he said repeatedly, "Oh, you just think this is like a narrow, legal dispute over what the term facilitate means." And that's just false and misleading, right? He's ignoring the fact that the Supreme Court did not say that the government has an obligation only to facilitate his re-entry into the United States or his return to the United States. The court had said you have to facilitate his release from the prison. If you read the transcript, I think that Ensign never acknowledged that's what the order said. And so they're kind of deliberately obfuscating what the court's order is in order to serve their legal interest in the case.

Another thing that developed in the last 24 hours with this case is that we have a U.S. senator, Sen. [Chris] Van Hollen, traveling to El Salvador as of this morning to try and negotiate Abrego Garcia's return. I am curious how that impacts the court proceedings if he's successful, if he's unsuccessful.

I don't think I really see an impact on the court case. The district court judge's initial order and the Supreme Court's order refusing to stay that order, they were both really clear. There's an obligation on the part of the executive branch, the part of the government that unlawfully removed Mr. Abrego Garcia from the country is they have a legal obligation to take steps to get him released from this prison and get him back to United States. And so nothing that others, whether they're public officials or private actors, do to try to negotiate or effectuate his release is going to relieve the executive branch of that obligation until Mr. Abrego Garcia is out of the prison and back in this country.

What do you think the rest of the country needs to take away from this incident, how it's playing out in court, how the government is approaching complying or not complying with this court order, or all of these court orders amid this immigration crackdown that we're seeing?

I mean, I think one of the most important takeaways is that, up until this point, courts — including the Supreme Court, I think, when it issued the order in this case — have operated on a kind of presumption of regularity that presumably the executive branch in good faith is going to listen to what courts say and try to effectuate what courts have asked them to do. That was also true in the Alien Enemies Act case where the Supreme Court didn't grant the plaintiffs the relief they wanted but did say quite clearly the federal government has an obligation to make sure that people who it wants to deport, pursuant to the Alien Enemies Act, have an adequate opportunity to file a habeas petition to seek due process protections prior to their deportation from the country. There, just like here, the executive branch seems to be making repeatedly clear — like, if there was any doubt before, there should be no doubt now — that they have no interest in affording any more process than the least they can manage to squeeze out of those court opinions.

In Colorado, a district court held [Tuesday] that the government hadn't even guaranteed that a person who was going to be deported under the Alien Enemies Act would be given even 24 hours notice of the deportation. So it's really hard to understand how that could amount to a reasonable opportunity to seek due process protection if you're afforded not even 24 hours notice of your deportation.

That's the way that the executive branch has been proceeding. The thing that the public needs to understand, the thing that courts will likely respond to, is that the only solution, really, to guarantee that people receive the legal process that they are entitled to, is for courts to not permit any deportation until that process has been given. I think what people are going to seek increasingly are broad, class-wide protection in place in advance of any attempt by the government to deport people so that no one's deported in advance of being able to get these protections because it's clear that the government isn't going to afford people protections after they've already been deported.

It's a very poignant point in a moment where it seems almost dizzying to try and make sense of the fact that we're getting these court orders, we're not immediately seeing compliance with the court orders, and like we discussed earlier, we saw this with the Trump legal teams' approach in his personal cases. Seeing it play out at a government level is just...

There are always going to be mistakes and errors. Historically, there are always instances in which the government violates the law. But if, if we're in a world right now where it's recently clear that we can't fix mistakes or illegalities after the fact, then it does have to be stopped before they happen. That's not the way that courts often like to proceed. Courts like to proceed presuming that the government's acting in good faith, presuming that they're not going to engage in unlawful actions. Courts want to proceed slowly. But that becomes more difficult for courts in this environment when they can't count on the government to do what they're asking.

Shares